jjohnson

Chief petty officer

Posts: 144

Likes: 219

|

Post by jjohnson on Feb 13, 2020 21:08:22 GMT

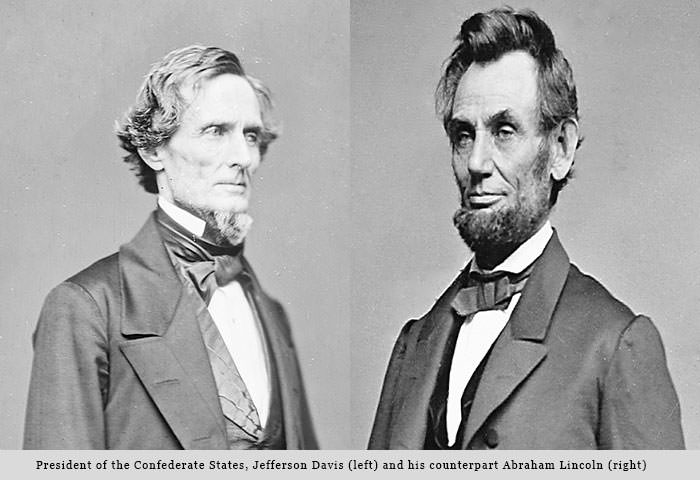

Chapter 10: Finishing the War in 1863Governor Parker Reminds Us of the Cause of War

New Jersey Governor Parker noted this year: " Slavery is no more the cause of this war than gold is the cause of robbery." Lincoln Comes to Gettysburg

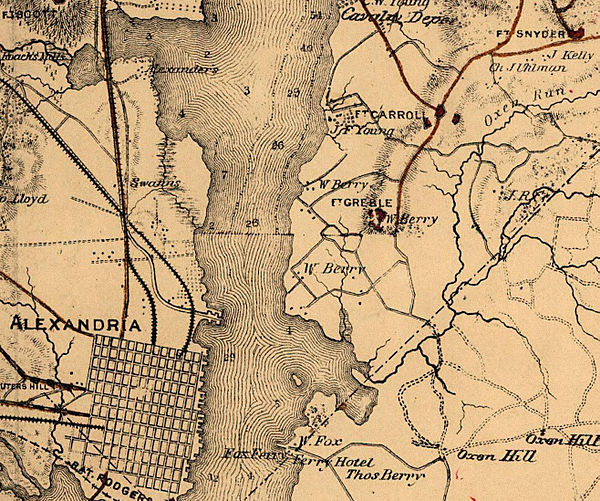

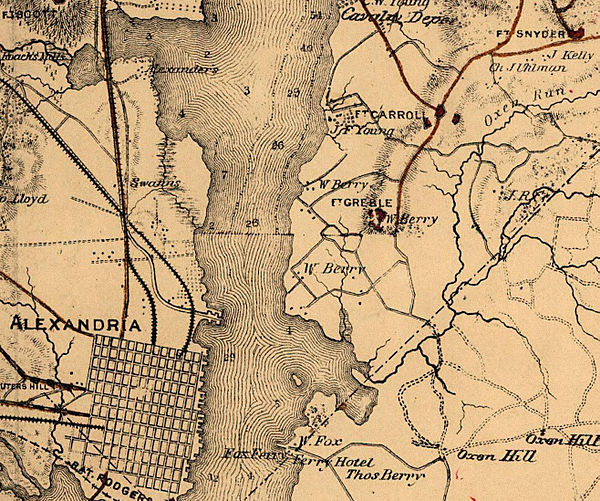

Lee was in Maryland on the 4th, and Lincoln got the report of the casualties and the response from Meade not even pursuing Lee he was furious, but realized he had a great chance for a propaganda victory, and pulled out the paper from his desk he had shelved nearly a year prior. By train, Lincoln made it to Gettysburg, and had a platform built for him by the troops. Members of his administration and members of the Pennsylvania, New York, and New Jersey political class and newspapermen were there for his address.  Lincoln amongst the troops Lincoln amongst the troops On July 6th, Abraham Lincoln made what would come to be called the Gettysburg Proclamation, incorporating portions of his old Emancipation Proclamation, declaring that the Union armies would be enforcing freedom of the southern slaves in areas under their control still in rebellion as a military measure. The Proclamation specifically exempted areas under Union control or border states, a point of contention in later decades with Lincoln mythologists who tried to describe him as "the Great Emancipator." Newspapers across the north would show the new Medal of Honor, which would be awarded to over 85 Union troops for their actions at Gettysburg alone, and praising Meade for having run the Confederates out of the north and breathlessly describing the valor of the Union troops in their deeds, and how they saved Harrisburg, New York, and New England from the depredations of the monstrous and devilish Rebels, who wanted to enslave northern blacks and take women and children with them down south. Lincoln himself gauged the reaction to his speech, saying it was " a flat failure and the people are disappointed." The measures in the proclamation to deport freed blacks were lambasted at home and abroad. The Patriot and Union of Harrisburg said, " The President acted without sense and without constraint in a panorama that was gotten up more for the benefit of his party than for the honor of the deed...We pass over the silly remarks of the President; for the credit of the nation we are willing that the veil of oblivion shall be dropped over them and that they shall no more be repeated or thought of." The Chicago Times said, " The cheek of every American must tingle with shame as he reads the silly, flat, and dishwatery utterances of the man who has to be pointed out to intelligent foreigners as the President of the United States." The London Times said: " Anything more dull and commonplace it would not be easy to reproduce." Lincoln's vapid speech declaring his intent to emancipate the slaves, enlist them, and once they helped conquer the South, to be deported to a foreign country was seen as duplicitous and dishonorable. This marked the beginning of the turn against Lincoln amongst those supporting him in the public, with those able to do so to support the Confederacy with small 'subscriptions' for helping get out from under such a tyrant as to use an entire race of people simply for conquering a part of the country that wished for the freedom the thirteen colonies asked for not 80 years prior. Lincoln's threat of war against any who would support the South may have scared off European support for a time, but the groundswell from the lower classes and a growing number of merchants would soon turn things against him. Lee would return to Maryland west through Chambersburg, PA, then Hagerstown, MD, and back into Virginia over the next fortnight through Winchester, returning to the area around Fredericksburg to act as a front line in case of pursuit by the Union troops. Having foraged north and replenished his army, Lee, along with Stuart, Jackson, Longstreet, Ewell, and AP Hill would all be praised for their actions in newspapers across the south, telling readers this was a great victory for the South, and the north should be expected to give up the invasion within only a few months. The London Spectator called his speech "a very sad document," and a "hypocritical sham." The London Standard said it was intentionally meant to "deceive England and Europe." The Times of London denounced his speech as "the wretched makeshift of a pettifogging lawyer," a man who was making his best attempt to "excite a servile war in the States he cannot occupy with his armies." In Ireland, the Belfast News called his proclamation "the latest and foulest crime perpetuated by the Lincoln administration." The editor wrote that this was nothing more than a "permit to murder men and rape women." He continued that Lincoln's "cruel and contemptible outburst" was the greatest example of vindictiveness ever seen from a so-called "Christian" dictator. He called all of Europe to rise up in protest, and to do all they could and necessarily do to try to stop the coming bloodbath. Yankee abolitionist Lysander Spooner publicly excoriated Lincoln, writing that he and his party did not abolish slavery as " an act of justice to the black man himself, but only as 'a war measure,' and because they wanted his assistance, and that of his friends, in carrying on the war they had undertaken for the maintaining and intensifying that political, commercial, and industrial slavery, to which they have subjected the great body of the people, both black and white." The text of Lincoln's Gettysburg Proclamation, which declared free all slaves in States not currently under Union occupation, but kept them in bondage where the Union occupied, struck many as duplicitous, including William Seward, who said, " We show our sympathy with slavery by emancipating slaves where we cannot reach them, and holding them in bondage where we can set them free." The London Spectator noted that the President's way of thinking " is not that a human being cannot justly own another, but that he cannot own him unless he is loyal to the United States." The State of Illinois reacted by issuing its own Emancipation Proclamation: " That the emancipation proclamation of the president is as unwarrantable in military as in civil law, a gigantic usurpation, at once converting the war, professedly commenced by the administration for the vindication of the authority of the constitution, into the crusade for the sudden, unconditional, and violent liberation of 3,000,000 of negro slaves; a result which would not only be a total subversion of the federal Union, but a revolution in the social organization of the Southern States. The proclamation invites servile insurrection as an element in this emancipation crusade, a means of warfare, the inhumanity and diabolism of which are without example in civilized warfare, and which we denounce, and which the civilized world will denounce, as an ineffaceable disgrace to the American name." Later on, even Lincoln admitted in a letter to Treasury Secretary Salmon Chase, "The original proclamation has no constitutional or legal justification..." and he said in September of 1862 to a group of abolitionist ministers that it was pointless to issue a proclamation for emancipation, since it would "necessarily be inoperative, like the Pope's bull against the comet." In writing the document, which in the 20th century would go on to become a more valued speech, Lincoln was noted by letters and recollections of his own words in saying that it was a 'war measure,' saying: "I view this matter as a practical war measure, to be decided on according to the advantages or disadvantages it may offer to the suppression of the rebellion." It would, he hoped, siphon off southern blacks from being used to support the Confederate war effort, in food, and in the armies, weakening the enemy; it could foment a servile insurrection, forcing soldiers home to suppress it; allow northern blacks to be allowed into the army since they were no longer legally 'property' and therefore act as ideal replacements for white soldiers, and to be 'purchased' as 'substitutes,' as was legal at the time, bolstering northern numbers and reducing southern numbers. General Grant wrote: " I have given the subject of arming the negro my hearty support. This, with the emancipation of the negro, is the heaviest blow yet given the Confederacy...by arming the negro we have added a powerful ally. They will make good soldiers and taking them from the enemy weakens him in the same proportion they strengthen us. I am therefore most decidedly in favor of pushing this policy to the enlistment of a force sufficient to hold all the South falling into our hands and to aid in capturing more." Rather than fomenting a slave revolt, as he may have hoped, southern blacks continued to support the Confederate Army and Navy. A quarter of the Ordnance Department was black, and while the Confederate Army hadn't officially enlisted blacks, States were doing so, by the voluntary enlistment of free blacks. From Louisiana, Jacques Esclavon, Lufray Pierre-August, Jean Baptiste Pierre-August, and other free men of color served to try to free New Orleans from Union occupation. Gabriel Grappe, Charles Lutz, Levin Graham, Peter Warren, Henry Love, Kiram Kendael, Joe Warren, Dam Humphreys, George Briggs, Hardin Blackwell, Joe McConnel, Daniel Robinson, Fielding Rennolds, and more went to battle against the Union armies invading their homes, as they viewed it. In Washington DC, white Union soldiers rioted against the Gettysburg Proclamation*, stoning blacks they hunted down, including black Union soldiers serving to restore the Union. *This actually happened, but in February 1863, according to Reveille in Washington, 1860-1865. After several days of his Gettysburg Proclamation, however, Lincoln admitted that it did fail in several respects in a letter to his Vice President Hamlin: My Dear Sir: Your kind letter of the 25th is just received. It is known to some that while I hope something from the proclamation, my expectations are not as sanguine as are those of some friends. The time for its effect southward has not come; but northward the effect should be instantaneous.

It is six days old, and while commendation in newspapers and by distinguished individuals is all that a vain man could wish, the stocks have declined, and troops come forward more slowly than ever. This, looked soberly in the fae, is not very satisfactory. We ahve fewer troops in the field at the end of six days than we had at the beginning - the attrition among the old outnumbering the addition by the new. The North responds to the proclamation sufficiently in breath; but breath alone kills no rebels.

I wish I could write more cheerfully; nor do I thank you the less for the kindness of your letter. Yours very truly, A. Lincoln.A Little Bribery to Go Around

By personal request of Abraham Lincoln, Secretary of War Edwin Stanton sent letters to the commanding officers of the 25th and 27th Maine regiments on June 28th, asking them to remain beyond their contracts due to the invasion of Pennsylvania by General Lee and his army. The 25th Maine declined, but the 27th was asked and over 300 volunteered to remain in defense of Washington during what would later be called the Gettysburg Campaign. Colonel Wentworth delivered the message to the Secretary, and when he did, he was informed that " Medals of Honor would be given to that portion of the regiment that volunteered to remain." When the battle at Gettysburg ended, they left Washington for home on July 4th, reuniting with the rest of the regiment to muster out on the 17th. By war's end, the promise was fulfilled, and the men got Medals of Honor for staying beyond their contracts; there was no agreeable list, and 864 medals ended up being made, distributed by Colonel Wentworth to the men he remembered as staying behind with him. Over 60 years later, Congress would purge these medals in 1917, as the actions of the regiment did not meet the criteria for receiving such a medal. *This actually happened. A Political Thanksgiving (July 15) With his Gettysburg Proclamation, intended to turn a battlefield loss into a propaganda victory, having failed in the press and abroad, and seen for the naked fraud that it was, Lincoln, ever the political animal, sought to find something else to help shore up support for the failing war support on the part of the Northern public who were feeling more despondent with each passing month, as well as more hostile and apathetic. So, to help appear patriotic and more religious than he really was, he made a Thanksgiving Proclamation to set aside August 6 as a holiday to thank God for the north's military victories, or as he put it, "Almighty God's signal and effective victories." Proclamation: It has pleased Almighty God to hearken to the supplications and prayers of an afflicted people and to vouchsafe to the Army and the Navy of the United States victories on land and on the sea so signal and so effective as to furnish reasonable grounds for augmented confidence that the Union of these States will be maintained, their Constitution preserved, and their peace and prosperity permanently restored. But these victories have been accorded not without sacrifices of life, limb, health, and liberty, incurred by brave, loyal, and patriotic citizens. Domestic affliction in every part of the country follows in the train of these fearful bereavements. It is meet and right to recognize and confess the presence of the Almighty Father and the power of His hand equally in these triumphs and in these sorrows:

Now, therefore, be it known that I do set apart Thursday, the 6th day of August next, to be observed as a day for national thanksgiving, praise, and prayer, and I invite the people of the United States to assemble on that occasion in their customary places of worship and in the forms approved by their own consciences render the homage due to the Divine Majesty for the wonderful things He has done in the nation's behalf and invoke the influence of His Holy Spirit to subdue the anger which has produced and so long sustained a needless and cruel rebellion, to change the hearts of the insurgents, to guide the counsels of the Government with wisdom adequate to so great a national emergency, and to visit with tender care and consolation throughout the length and breadth of our land all those who, through the vicissitudes of marches, voyages, battles, and sieges, have been brought to suffer in mind, body, or estate, and finally to lead the whole nation through the paths of repentance and submission to the divine will back to the perfect enjoyment of union and fraternal peace. In witness whereof I have hereunto set my hand and caused the seal of the United States to be affixed.

Done at the city of Washington, this 15th day of July, A. D. 1863, and of the Independence of the United States of America the eighty-eighth.

ABRAHAM LINCOLN.

By the President:

WILLIAM H. SEWARD, Secretary of State .His proclamation called the seceding states' efforts to defend their independence a "needless and cruel rebellion," despite having endured years of northern slander, murder supported by people from Massachusetts in the form of John Brown and his raids, and lack of support for spending money in the south from tariff revenue derived from southern cotton exports. No Betrayals by Confederates (After Gettysburg) One Confederate officer, Colonel W. S. Christian of the 51st Virginia Infantry had been captured by the Union on the retreat from Gettysburg, along with a number of black soldiers, and imprisoned on Johnston's Island. One of the prisoners with him, a black man named George, was given several opportunities to turn against the Confederates and fight for the Union, but he refused the offer from the prison commander over and over, saying: " Sah, what you want me to do is desert I ain't no deserter and down South, where we live, deserters always disgrace their families. I'se got a family doen home, sah, and if I do what you tell me, I will be a deserter and disgrace my family, and I am never going to do that." Colonel Christian recalled himself after the end of the war: " My recollection is that there were thirteen Negroes who spent that dreadful winter of 1863-64 with us at Johnston's Island and not one of them deserted or accepted freedom though it was urged upon them time and again." Another officer, Captain Robert Park of the 12th Alabama Regiment was imprisoned in Baltimore, Maryland, with a servant from Georgia, Charles, who refused to take the oath the Union troops were trying to make them all take. Captain Park recalled, " I received a letter from Abe Goodgame, a mulatto slave belonging to Colonel Goodgame of my regiment, who was captured in the Valley and is now a prisoner confined at Fort McHenry, having positively refused to take the oath. He asks me to write his master when I am exchanged and tell him of his whereabouts, and that he is faithful to him." Jackson Expedition (July 12) During his Vicksburg Campaign, Major General Ulysses S. Grant's Army of the Tennessee captured Jackson back on May 14th, but evacuated to move west to capture Vicksburg. During the siege on Vicksburg, General Johnston had been gathering troops at Jackson intent upon relieving Lt. Gen. John Pemberton's garrison. He cautiously advanced his 30,000 soldiers to the rear of Grant's army which had surrounded Vicksburg. In response, Grant ordered Sherman to deal with the threat from Johnston. By July 1st, Johnston's force was in position along Big Black River. Sherman used his newly arrived IX Corps to counter. On the 5th, the day after Vicksburg's surrender, Sherman was free to move against Johnston. Johnston hastily withdrew his force across the Big Black River, and Champion's Hill battlefields with Sherman in pursuit. Sherman took with him the IX Corps, XV Corps, XIII Corps, and a detachment of the XVI Corps, giving him 40,000 troops.  Sherman's Siege of Jackson Sherman's Siege of Jackson

On the 10th, the Union Army took up position around Jackson. The heaviest fighting happened on the 11th, during an unsuccessful Union attack. Brig. Gen. Jacob Lauman ordered a brigade under Col. Isaac Pugh to attack the Confederate defensive works manned by Brig. Gen. Daniel Adams's brigade. There were heavy casualties, but instead of risking his entrapment in the city like Vicksburg, Johnston chose to evacuate, and left on the 16th, allowing Sherman to occupy the city the next day. This ended the threat to Union control of Vicksburg. Command

-US: William Tecumseh Sherman -CS: Joseph E. Johnson Strength

-US: 40,000 -CS: 30,000 Casualties

-US: 350 killed, 980 wounded, 210 missing -CS: 71 killed, 304 wounded, 564 missing New York Draft Riots (July 13 - 16, 1863) A series of violent disturbances rocked New York in the middle of 1863, as a result of the draft recently passed by Congress. Many white lower-class people and many immigrants were being drafted into the war, while richer men could pay $300 (roughly $9200 in 2017) to get out of the draft and hire a substitute. Additionally, many of those same white people feared the competition by free black people, coupled by the historic racism inherent in northern society, leading to riots. While it was at first a protest on the draft, the riots devolved into a race riot, with many white Irish immigrants especially, attacking and lynching black people throughout the city. Over 50,000 whites rioted against the military draft in New York, but they vented their anger not on Lincoln or the government, but on blacks. Even black women and children were murdered, and their corpses were set on fire in the streets. One little black girl, found hiding under a bed, who was under the care of some Catholic priests, was also dragged out onto the street and killed. White abolitionists were also tracked down, attacked, and their property was looted and torched.* The official death toll was around 200 black individuals beaten, hung, or shot by New Yorkers, but locals counted at least 500 mostly black deaths. The severity of those riots meant that for over 50 years, no black person lived in New York, Brooklyn, or the Bronx, with the black people fleeing to Kearny in New Jersey to escape the rioters. President Lincoln had to divert several militia regiments from Gettysburg to control the city, not arriving until the second day of the riot, by which time many public buildings had been burned, ransacked, or destroyed, including two Catholic churches, homes of various abolitionists or sympathizers, many black homes and schools, and the Colored Orphan Asylum on 44th Street and 5th Avenue, which was burned to the ground. The black population of the area fell below 5,000 for the first time in decades. For several days afterwards, the bodies of black Americans could be seen hanging from trees and lampposts, the cruel work of white New Yorkers. A northern newspaper, the Christian Recorder, reported: These rioters of New York could not be satisfied with their resistance of the draft and doing all the damage they could against the government and those of the white citizens who are friends to the administration, but must wheel upon the colored people, killing and beating every one whom they could see and catch, and destroying their property...A gloom of infamy and shame will hang over New York for centuries.*This actually happened, from a book "American Patriots: The Story of Blacks in the Military from the Revolution to Desert Storm." Peterhoff Affair

A ship named the Peterhoff sailed from Falmouth, Cornwall on January 27, 1863. She was a blockade runner. The tightening blockade had been worrisome to textile manufacturers and others in the British public. On February 20th, she was boarded and searched by the USS Alabama off St Thomas in the Danish West Indies. The Alabama found her papers in order and released her. Peterhoff then entered the harbor, where two US Navy ships, under command of Acting Rear Admiral Charles Wilkes were at anchor. Wilkes, who was already notorious for the part he played in the Trent Affair, ordered the Peterhoff to be boarded by the USS Vanderbilt just after she left harbor on the 25th. Peterhoff had papers stating that she was bound for Tampico Alto in Mexico, but a sailor on board let slip she was really bound for Texas, just across the border line. This comment was taken as sufficient justification for the Vanderbilt to seize the ship as a blockade runner, and she was sent to Key West, a Union foothold in Florida. Both the British and Danish governments vigorously protested the seizure and treatment of their subjects, but the ship was eventually condemned by a New York prize court, and bought by the Union Navy. She would be recommissioned in February 1864 with Acting-Volunteer Lieutenant Thomas Pickering in command, assigned to the North Atlantic Blockading Squadron. United Kingdom

The reaction was firm over in the United Kingdom. Lincoln was interfering with British subjects and property. Given the recent Gettysburg Proclamation, though, the elites could not afford to come out and recognize the Confederacy, as the middle class and factory workers sided with the Union and their cousins who were living and fighting there. Some Irish, Scottish, Welsh, and even Channel Islanders had gone over to join the Confederacy, but not many. Given this second affair, the US was cooling relations with the United Kingdom, not helping matters much, given Lincoln's lack of awareness of consequences of his administration's actions and reactions. US envoys to the United Kingdom were working diligently to prevent the Confederates from ordering and receiving seagoing vessels to outfit their navy, and so far had done quite a good job. Charles Francis Adams, Jr., the grandson of the Federalist President John Adams, was an effective minister so far, but would soon find himself delayed and his social calendar changing. At Birkenhead, the shipyards of John Laird and Sons, several more keels would be finished by the end of July, with Commander James Bulloch taking ownership of 8 stocked ships similar to the CSS Alabama. They were not armed in British waters, so the United Kingdom was not violating neutrality by building them, and the US Navy was requested to take port elsewhere in the United Kingdom under various auspices. Soon the CS Navy would gain 9 more ships sailing from the Azores: CSS Congress, CSS Enterprise, CSS President, CSS Confederate States, CSS Confederacy, CSS Constitution, CSS Charleston, CSS Fort Sumter, CSS Secession. CSS Secession at sea CSS Secession at sea. These ships, like the CSS Alabama under command of Admiral Raphael Semmes, would act as commerce raiders, hoping to affect US trade on the high seas. One side effect of these vessels was the number of whaling ships either sunk or caught, which incidentally helped save three species of whales from extinction. Another side effect was, based on the act authorizing the navy saying: "All the Admirals, four of the Captains, five of the Commanders, twenty-two of the First Lieutenants, and five of the Second Lieutenants, shall be appointed solely for gallant or meritorious conduct during the war." On the CSS Congress, the only available person to take a Second Lieutenant position was a free black of color, Henry Jones, who became the first black officer in the Confederate Navy and the Confederate Armed Forces; he had saved the captain from a savage beating from the USS Kearsarge, when three other men ducked or avoided fire. Captain Harrison Cocke made the promotion in late 1864, having served with him for over a year on the Congress, and two years prior. Jones would also be the first black to receive the Confederate Medal of Honor in the CS Navy. Utah

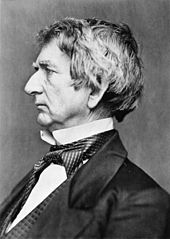

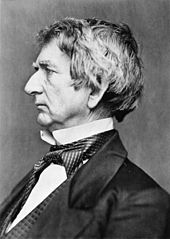

Over in Utah, the Mormons had had another request for statehood rejected, and they in reaction ceased consideration of helping the Union efforts. Captain Lot Smith and his militia of around 200 men had done their duty in securing the overland mail route and securing the telegraph lines to the east, but otherwise would not make any meaningful martial contribution to the Union efforts. Just five years prior, President James Buchanan had replaced Brigham Young as territorial governor with a non-Mormon appointee, and sent a fifth of the US army to make sure he arrived safely in Utah. The Mormons believed the Civil War was God's retribution against the US for its past mistreatment of their church, and their failure to protect their prophet, Joseph Smith, who was killed by a mob in Illinois in 1844.  Brigham Young, 1863 Brigham Young, 1863

Young parsed his words in a statement saying Utah was "firm for the Constitution." Privately, he said he “earnestly prayed for the success of both North & South.” He was hoping a long war would distract Washington enough to let the Mormons govern themselves. When Lot Smith's men were asked to re-enlist, they declined; Congress had carved out Nevada from the west of Utah, and passed an Anti-Bigamy Act, permitting federal prosecution of Mormon polygamists. More immediately, Young refused to consider the continued service of Lot Smith’s men because he learned that the Army had dispatched a brigade of California volunteers to garrison Utah for the remainder of the war. Col. Patrick Edward Connor, the unit’s commander, made no secret of his anti-Mormon animosity. In June of 1863, a Mormon journalist, Thomas Stenhouse, went to DC to find out Lincoln's policy regarding the Mormons. When Stenhouse asked Lincoln about his intentions in regard to the Mormon situation, Lincoln reportedly responded: “Stenhouse, when I was a boy on the farm in Illinois there was a great deal of timber on the farm which we had to clear away. Occasionally we would come to a log which had fallen down. It was too hard to split, too wet to burn, and too heavy to move, so we plowed around it. [That’s what I intend to do with the Mormons.] You go back and tell Brigham Young that if he will let me alone I will let him alone." De Stoeckl's Journey

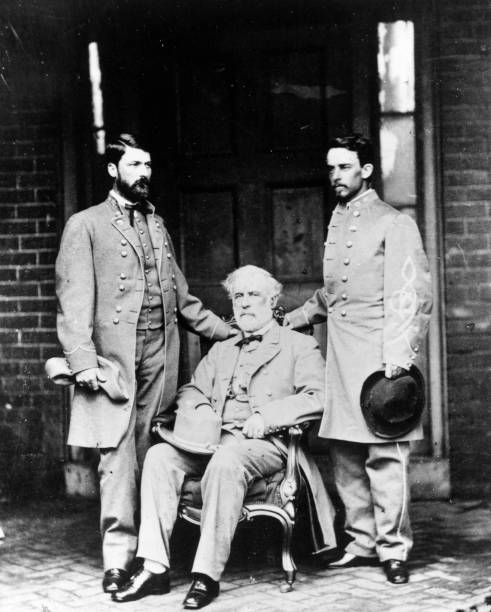

The Russian Minister to the United States, Eduard de Stoeckl, had met with the British officer Lt Col Arthur Fremantle in 1863 while the latter was on his way to New York to return to his homeland. Fremantle had given him a positive view of the southerners, quite in contrast to some of the stories that de Stoeckl had heard from his northern hosts. De Stoeckl had made overtures to the United States to purchase Alaska, but in view of the South now having disrupted Union trade, captured gold from the Union in Colorado, he might need to re-assess his views of the South. Eduard got permission to cross lines, and went south to see what Fremantle had only described for him. De Stoeckl journeyed to view the Army of Northern Virginia, being somewhat shocked at the close quarters between white soldiers and the black teamsters with them, who were acting as cooks, tailors, guards, and filling other positions in the army, not segregated as he had seen while in the North. He spoke with several colonels and several generals, including Lee, Jackson, and Longstreet, who answered his questions quite honestly about their goals. None told him they were looking to expand slavery; Lee himself told de Stoeckl he thought slavery was a moral evil, and worse for the white man than the black man. Jackson and Longstreet impressed de Stoeckl with their descriptions of the things Union soldiers had done - theft, rapine, burning civilian houses, and more - to southerners where they were invading. The Russian Minister spent a week with the army before journeying to northern Georgia and meeting with Bragg's army, and was suitably impressed with Patrick Cleburne, an Irishman fighting for the Confederates, as Arkansas was his new home. Cleburne had a sober view of the war, and had no real stake in slavery. In speaking with Cleburne, de Stoeckl learned the southern slaves were more like bonded servants than what he viewed as slaves. Southern slaves could own property, earn money, purchase their own freedom, and own businesses. Granted their rights were curtailed in comparison to white southerners, but the tales of beatings and whippings and separating families were in fact much rarer than he had been led to believe by his northern hosts. De Stoeckl spoke with Cleburne about Russian Emancipation which had occurred two years prior in 1861, which future historians would credit with the inspiration for his own Cleburne Manifesto, though other historians would cite other evidence that he would've issued the manifesto without having spoken to de Stoeckl. After spending roughly three months and three days in the South, de Stoeckl returned to DC and sent private correspondence to the Tsar back in Russia via his own trusted aids, avoiding the telegraph, which he knew was tapped, and regular mail, which he knew was being opened by the Lincoln administration. Prussian Training

Foreigners from Prussia served in notable positions in the southern army. Most notably, Heros von Borcke, who was a Lieutenant Colonel serving under JEB Stuart. Adolphus Heiman, a Brigadier General, was still alive and kicking*, and was helping train new recruits in Georgia in drill and moving in formation. Baron Robert von Massow, son of the Prussian King's chamberlain, was serving under John Mosby in the 43rd Virginia Cavalry Battalion, otherwise known as Mosby's Rangers. Justus Scheibert was a Prussian military observer who followed Lee at several battles, such as Chancellorsville and Gettysburg. He would return to Prussia in 1864, and write down his observations, placing them in several of Prussia's best libraries. What he wrote would help Prussia and a future unified Germany in five different wars. While Prussia overall sided with the Union efforts, many of the poor of Prussia would side with the Confederates and some would even risk coming to Mexico or even New York to cross lines and join the Confederate army. Bermuda

Col. Henry Feilden, Army of Tennessee, CSA Col. Henry Feilden, Army of Tennessee, CSA

The oldest British colony still in existence was founded by accident. In 1609, British had settled Bermuda as an extension of Virginia. Located about 640 miles off Cape Hatteras, NC retained close ties to the south. They sympathized with the US during the War for Independence, supplying them with ships and weapons in exchange for exemption from the embargo of the Continental Congress on colonies not in revolt. With independence, Bermuda became the HQ and dockyard for the Royal Navy's North America and West Indies Squadron, with a heavy build-up of regular British Army units for both defense and potential expeditions and campaigns, such as during the War of 1812, when most of the Atlantic ports of the US were blockaded by a fleet based in Bermuda. The Chesapeake Campaign, which included the Burning of Washington, was launched from Bermuda. During the War for Southern Independence, St George's, Bermuda, was the primary harbor from which British and European war material was being smuggled into the Confederacy aboard blockade runners (also built in the UK), and southern cotton traveled out in payment. The capture of US gold stabilized the Confederate Dollar and made smuggling more profitable, allowing goods to continue flowing, despite the growing blockade. After the Trent Affair, the UK built up their forces in Canada in defense of the colony, and after the Peterhoff affair, they began building up their naval forces in Bermuda to defend against a Union attack or to launch an invasion of the northern states, intended to capture New York. They also turned more of a blind eye to smuggling efforts which picked up more around December. Many British citizens did take part in the war on the Confederate side, including Colonel Henry Wemyss Feilding, who resigned his commission in the British Army to become an officer in the Confederate Army, William Watson, who served as a sergeant in the 3rd Louisiana Infantry before crewing blockade runners, and James William Hammond, who would aid the Confederate Navy procuring steam engine components and source a naval yard in North Carolina. Scottish-born Captain William Watson was another prominent volunteer as was Thomas Leslie Outerbridge, who crewed blockade runners. In Bermuda, close historic ties to the South, and the enticement to profiteer from the war by supplying the South allowed the Confederate agent to operate openly from the Globe Hotel at St. George's, but the US government's consul was attacked in the street and had his flagpole cut down on the 4th of July. Many Bermudians earned fortunes supplying the south during the war. Mexico

In 1861, conservatives in Mexico looked to the French leader Napoleon III to abolish the republic which had been led by liberal President Benito Juárez. France did favor the Confederacy, but had not yet given it diplomatic recognition, as it was waiting for the United Kingdom, and wanted to act in concert in that arena. The French expected a Confederate victory would facilitate French economic dominance in Mexico. France helped the Confederates by shipping urgently needed supplies through Brownsville, TX, Matamoros, and Tampico, Mexico. The Confederates themselves sought closer relations with Mexico. Juárez had turned them down, but the Confederates, unwisely, worked well with local warlords in northern Mexico, and with the French invaders. Mexico owed France debts and was reneging on payment, encouraging France to take part in Mexico's politics. Realizing that Washington could not intervene in Mexico as long as the Confederates controlled Oklahoma, Texas, and Rio Grande, France invaded Mexico in 1861, and in 1864, would install Austrian prince Maximilian I of Mexico as its puppet ruler in that year. Owing to shared convictions of the democratically elected governments of Juárez and Lincoln (who had barely gotten 40% of the popular vote in his own country), Matías Romero, the Mexican minister in Washington, mobilized support in the US Congress, raised money, soldiers, and ammo in the US for war against Maximilian. His mobilization was slowed though, due to the need for the Union to protect Colorado from further Confederate raids. Washington would simply protest France's violation of the Monroe Doctrine, but would not act until the war was over. Medical Experimentation on Prisoners of War

At Point Lookout, Maryland, the Union Army had more Confederates than it had tents or cabins in which to hold the prisoners. They couldn't exchange them, as they would go back to the fight. Union Prisoners of War, however, would simply go home, eroding the war effort on the part of the north. Another part of the difficulty of war was disease. Disease often killed more than gunshot wounds, and the War Department was looking for something to help, but doctors needed to test their medicines.  Secretary of War Edwin Stanton Secretary of War Edwin Stanton

Edwin Stanton, the Secretary of War, authorized the prisoner of war camps to allow doctors to use the prisoners to test their vaccinations and medicines on July 3rd, 1863. Starting at Point Lookout, prisoners were first given medications and injections, but when they started getting sick, other prisoners refused and nearly rioted to avoid the medications. By the hottest part of August, the guards at Point Lookout stopped giving prisoners food and water unless they took the medicines and injections. Some agreed, only because they were addled with hunger. Others continued until they were physically forced to take the medications, often having to be knocked out with the butt of a gun to stop struggling. By war's end, the camp would hold over 50,000 prisoners of war, and of those, 9,433 died, of which 5,419 had been medically experimented upon. General Jackson's View on Victory or Defeat

General Jackson noted somberly in a letter to President Davis: "If the North triumphs, it is not alone the destruction of our property, it is the prelude to anarchy, infidelity, the ultimate loss of free & responsible government on this continent." He urged the President to enlist massive numbers of blacks into the army to make up the manpower deficit. North America's Situation

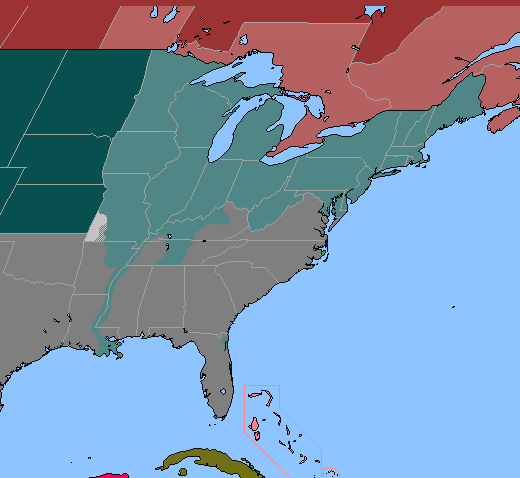

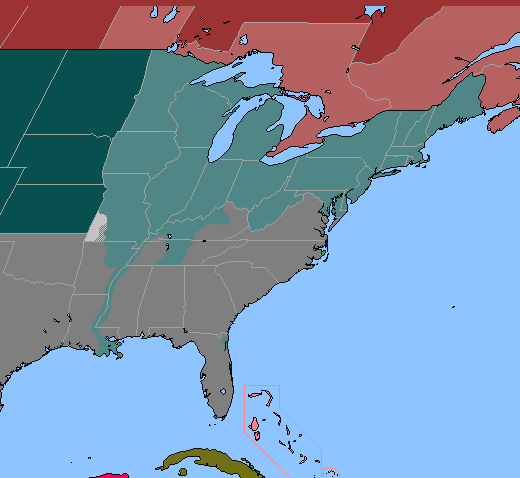

In June, the United States recognized the state of West Virginia, carved out of the Old Dominion. Idaho Territory was carved out of Nebraska and Washington Territory.  Lincoln Stuns in a Meeting Lincoln Stuns in a MeetingOn the 14th of August, Lincoln requested to have a group of blacks meet with him in the White House, the first free blacks ever to enter the building. The five who entered were hand-picked by Rev. James Mitchell, Lincoln's commissioner of emigration. Four were former slaves, and they were not rushed into the President's office. The group finally got to see him, and sat in stunned silence as he pulled out a crumpled-up paper from his famous stove-pipe hat, and began reading in his thin, alto voice: ...many men engaged on either side (of the war) do not are for you one way or the other...It is better for us both, therefore, to be separated...

There is an unwillingness on the part of our people, harsh as it may be, for you free colored people to remain with us...The colony of Liberia has been in existence a long time. In a certain sense it is a success...The question is, if the colored people are persuaded to go anywhere, why not there?...

The place I am thinking about for a colony is in Central America...The country is a very excellent one for any people...and especially because of the similarity of climate with your native soil, thus being suited to your physical condition...this particular place has all the advantages for a colony...The practical thing I want to ascertain is, whether I can get a number of able-bodied (black) men, with their wives and children, who are willing to go when I present evidence of encouragement and protection...I want you to let me know whether this can be done or not.

He continued, telling them: It is exceedingly important that we have (black) men at the beginning capable of thinking as white men...He closed: For the sake of your race, you should sacrifice something of your present comfort for the purpose of being as grand in that respect as the white people.Lincoln waited for their response, but it would take a few days from the stunned party. The brief letter he got was furious in tone, and to the point. They scolded Lincoln for campaigning for the deportation of black Americans and then asked him to mind his own business. Educated black leaders who found out about this conference were angered at Lincoln. Frederick Douglass wrote in a newspaper, Douglass' Monthly: The tone of frankness and benevolence which Mr. Lincoln assumes in his speech to the colored committee is too thin a mask not to be seen through. The genuine spark of humanity is missing in it. It expresses merely the desire to get rid of them... A New Jersey newspaper printed the response of one frustrated black citizen, calling the president meddlesome and impudent, and asked Lincoln to remember that in God's eyes, there was only one race - the human race. *this actually happened. See Abraham Lincoln Complete Works by Nicolay and Hay. Battle of Chattanooga (August 21) To keep the Confederates off-balance, Col. Joseph Wilder used his Lightning Brigade to keep D.H. Hill and Bragg focused on him while Rosecrans moved his army southwest of Chattanooga. The ruse worked, eventually leading Bragg to abandon Chattanooga for Georgia. The shelling of the town caught many in the town while they were praying and fasting. Richmond, VA

Following the events at Vicksburg, which cut the country in two, and Gettysburg, which were soon being seen as a loss to the Confederates, open talk of freeing and arming their slaves became more common. Tennessee's Confederate governor allowed blacks to be placed in non-combatant roles, and Alabama's legislature brought up a bill to conscript blacks, paid at the same rate as white soldiers, for non-combat duty within the army - soldiers, just soldiers not in combat. The First Black Chaplain (September 10) Reported in the Religious Herald newspaper, a Tennessee regiment was in need of a chaplain but was unable to find one, until a black man, Uncle Lewis, who accompanied the regiment in its maneuvers, was asked to conduct a religious service. The soldiers of the regiment were so pleased with his performance, that they asked him to serve as their chaplain, which Lewis did faithfully until the end of the war. The correspondent for the newspaper reported, "He is heard with respectful attention and for earnestness, zeal, and sincerity can be surpassed by none." For this Tennessee regiment, and the editors of the Richmond, VA newspaper, their black chaplain was a source of great pride. Battle of Chickamauga (September 19, 20)  Battle of Chickamauga, painting in the Milledgeville Capitol Rotunda, GA Battle of Chickamauga, painting in the Milledgeville Capitol Rotunda, GA

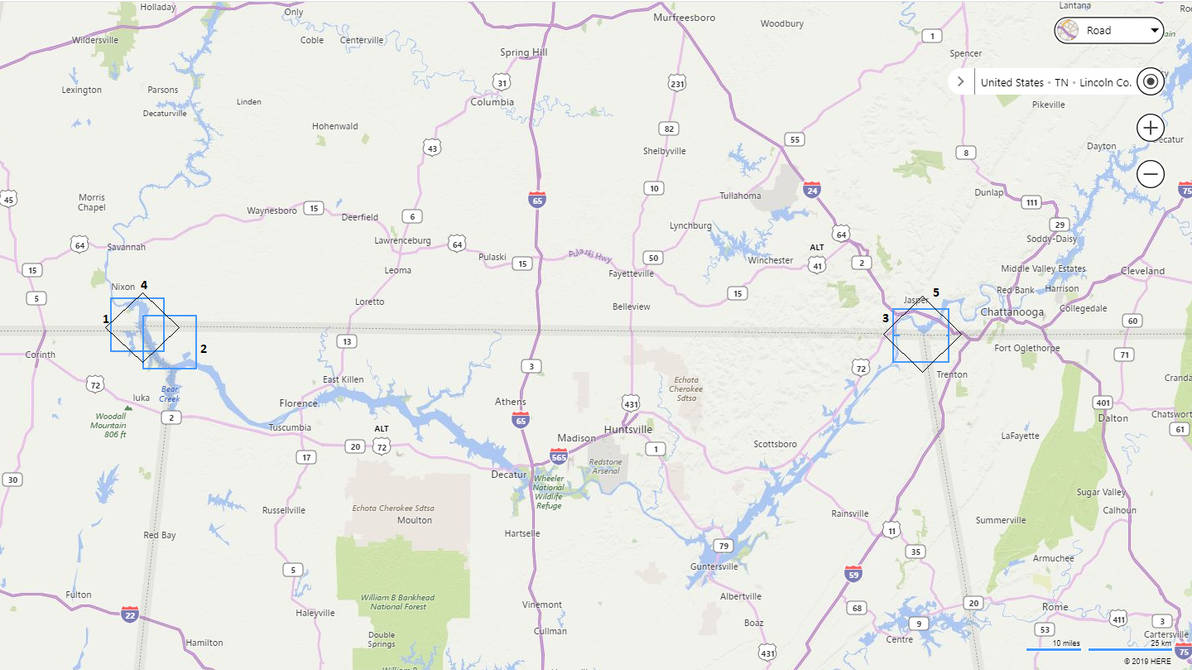

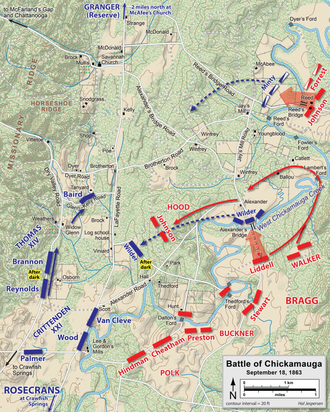

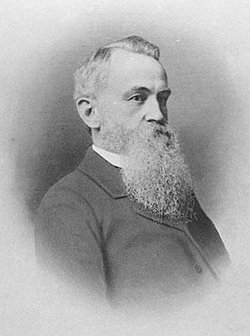

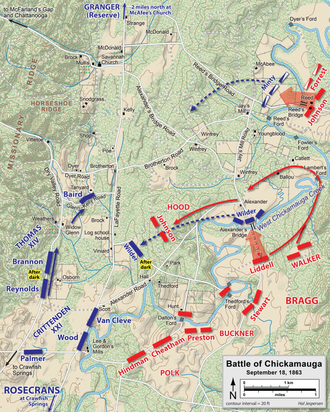

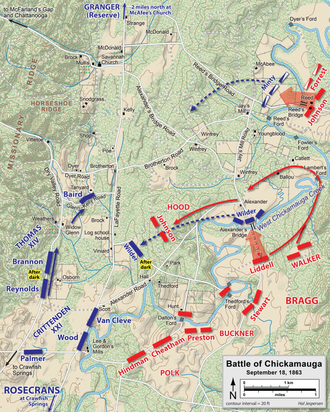

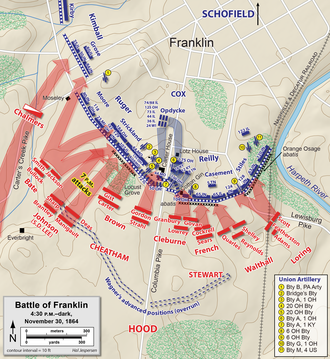

Confederate Brigadier General Bushrod Johnson's division took the wrong road coming from Ringgold, but eventually headed west on Reed's Bridge Road on the 18th of September. They had come from Mississippi to reinforce Bragg, just as Longstreet came from Virginia to reinforce the beleaguered Army of Tennessee. At 7 AM, his men encountered cavalry pickets from Col. Robert Minty's brigade, which was guarding the approach to Reed's Bridge. He was outnumbered 5-to-1, so Minty's men eventually withdrew across the bridge, after being pressured by elements of Forrest's cavalry, but they couldn't destroy the bridge to prevent Johnson's men from crossing. At 4:30 PM, when Johnson reached Jay's Mill, Maj. Gen. John Bell Hood of Longstreet's Corps arrived from the railroad station at Catoosa and took command of the column. He ordered Johnson to use the Jay's Mill Road instead of Brotherton Road, as Johnson planned originally. At Alexander's Bridge to the south, Union Colonel John Wilder's mounted infantry brigade defended the crossing against the approach of Walker's Corps. Armed with Spencer repeating rifles and Captain Lilly's four guns from the 18th Indiana Battery, Wilder was able to hold off a brigade of Brig. Gen. St. John Liddell's division, which suffered 105 casualties against Wilder's superior firepower. Walker moved his men downstream a mile to Lambert's Ford, which was an unguarded crossing, and was able to cross around 4:30 PM, which was considerably behind schedule. Wilder, who was concerned about his left flank after Minty's loss of Reed's Bridge, withdrew and established a new blocking position east of Lafayette Road, near the Viniard Farm.  September 18 positioning by both sides September 18 positioning by both sides

By the time the sun set, Johnson's division was halted in front of Wilder's position. Walker crossed the creek, but his troops were well scattered along the road behind Johnson. Buckner had only been able to push one of his brigades across the creek at Thedford's Ford. Polk's troops were facing Crittenden's at Lee and Gordon's Mill, and D.H. Hill's corps guarded crossing sites to the south. Though Bragg had achieved some degree of surprise against his Union opponents, he failed to exploit it strongly. Rosecrans, observing the dust raised by the marching Confederates in the morning, anticipated Bragg's plan. He ordered Thomas and McCook to Crittenden's support, and while the Confederates were crossing the creek, Thomas began to arrive in Crittenden's rear. September 19

Morning of the 19th Morning of the 19th

Yesterday's movement of Maj. Gen. George Thomas's XIV Corps put the left flank of the Army of the Cumberland further north than Bragg expected when he formulated his attack plan for the 20th. Maj. Gen. Thomas Crittenden's XXI Corps was concentrated around Lee and Gordon's Mill, which Bragg had assumed was the left flank, but Thomas was arranged behind him, covering a wide front from Crawfish Springs to the McDonald Farm. Maj. Gen. Gordon Granger's Reserve Corps was spread out along the northern end of the battlefield from Rossville to McAfee's Church. Bragg's plan was for an attack on the supposed Union left flank by the corps of Maj. Gens. Simon Buckner, John Hood, and W.H.T. Walker, screen by Brig. Gen. Nathan Bedford Forrest's cavalry to the north, Maj. Gen. Benjamin Cheatham's division in the center in reserve, and Maj. Gen. Patrick Cleburne's division in reserve at Thedford's Ford. Maj. Gen. Thoman Hindman's division faced Crittenden at Lee and Gordon's Mill, and Breckinridge's faced Negley. The Battle of Chickamauga began almost by accident, when pickets from Union Col. Daniel McCook's brigade of Granger's Reserve Corps moved toward Jay's Mill looking forwater. McCook moved from Rossville on the 18th to aid Col. Robert Minty's brigade. His men established a defensive position several hundred yards northweset of Jay's Mill, about as far away as the 1st Georgia Cavalry waited through the night south of the mill. About the time McCook sent a regiment to destroy Reed's Bridge, Brig. Gen. Henry Davidson from Forrest's Cavalry Corps sent the 1st Georgia forward, and they encountered some of McCook's men near the mill. McCook was ordered by Granger to withdraw back to Rossville, and his men were pursued by Davidson's troopers. McCook encoutnered Thomas at the LaFayette Road, having finished an all-night march from Crawfish Springs. McCook reported to Thomas that a single Confederate infantry brigade was trapped on the west side of Chickmauga Creek; Thomas told Brannan's division to attack and to destroy it.  Confederate troops advancing at Chickamauga Confederate troops advancing at Chickamauga

Brannan sent three brigades in response to Thomas's order, Col. Ferdinand Van Derveer, Col. John Croxton, and Col. John Connell sending their brigades in. Brannan's division held its ground against Forrest and his infantry reinforcements, but their ammo was running low, so Thomas sent Baird's division to assist, advancing two brigades forward with one in reserve. Brig. Gen. John King's brigade of US Army regulars relieved Croxton. The brigade of Col. Benjamin Scribner took up a position on King's right, and Col. John Starkweather's brigade remained in reserve. With their superior numbers and firepower, Scribner and King were able to start pushing back Wilson and Ector from Forrest's troops. Bragg decided to commit the division of Brig. Gen. Liddell to the fight, countering Thomas's reinforcements. Confederate Brigades under the commands of Col. Daniel Govan and Brig. Gen. Edward Walthall advanced along the Alexander's Bridge Road, smashing Baird's right flank. Both Scribner's and Starkweather's Union brigades retreated in panic, followed by King's regulars, who ran for the rear through Van Derveer's brigade. Despite the disorder, Van Derveer's men halted the Confederate advance with a concentrated volley at close range. Liddell's exhausted Confederates began to withdraw, and Croxton's brigade, returning to the action, pushed them back beyond the Winfrey field. Believing that Rosecrans was trying to move the center of the battle farther north than Bragg had planned for, Bragg began rushing heavy reinforcements from all parts of his line to his right, beginning with Cheatham's division of Polk's Corps, with five of the largest brigades of the Army of Tennessee. About 11 AM, Cheatham's men approached Liddell's halted division and formed on its left. Three Confederate brigades under Brig. Gens. Marcus Wright, Preston Smith, and John Jackson formed the front line, and Brig. Gens. Otho Strahl and George Maney commanded the brigades in the second line. Their advance overlapped Croxton's brigade, and had no difficulty pushing it back. As Croxton withdrew, his brigade was replaced by Union Brig. Gen. Richard Johnson's division of McCook's XX Corps, near the LaFayette Road. Johnson's lead brigades, under Col. Philemon Baldwin and Brig. Gen. August Willich engaged Jackson's brigade, protecting Croxton's withdrawal. Although he was outnumbered, Confederate Brig. Gen. John Jackson held under the pressure till his ammo ran law and he called for reinforcements. Cheatham sent in Maney's small brigade to replace Jackson, but they were no match for the two larger Union brigades and Maney was forced to withdraw because both his flanks were crushed.  Early afternoon maneuvers on the 19th Early afternoon maneuvers on the 19th

More Union reinforcements arrived shortly after Johnson. Maj. Gen. John Palmer's division of Crittenden's corps marched from Lee and Gordon's Mill and advanced into battle with three in-line brigades - Hazen, Cruft, and Grose - against the Confederate brigades of Wright and Smith. Smith's brigade took the brunt of the attack, and was replaced by Strahl's brigade, which also had to withdraw under the pressure. For a third time, Bragg ordered a fresh division to move in, Maj. Gen. Alexander Stewart's (Buckner's corps) from its position at Thedford Ford around Noon. Stewart encountered Wright's retreating brigade at Brock Farm, and decided to attack Van Cleve's position on his left, made under his own authority. Brig. Gen. Henry Clayton's was the first to hit them at Brotherton Farm. They fired till their ammo ran out, when they were replaced with Brig. Gen. John Brown's brigade. He drove Beatty's and Dick's men from the woods east of LaFayette Road, and paused to regroup. Stewart committed his last brigade, Brig. Gen. William Bate's, about 3:30 PM, and routed Van Cleve's division; during the fight, Van Cleve was shot through the lung and bled out. Hazen's brigade was caught up in the retreat as they were replenishing their ammo. Col. James Sheffield's brigade from Hood's division drove back Grose's and Cruft's brigades. Brig. Gen. John Turchin's brigade (Reynold's division) counterattacked and briefly held off Sheffield, but the Confederates had caused a major penetration into the Union line at Brotherton and Dyer fields. Steward didn't have sufficient men to maintain his position, and was forced to order Bate to withdraw east of LaFayette Road. About 2 PM, Brig. Gen. Bushrod Johnson's division of Hood's Corps encountered the advance of Union Brig. Gen. Jefferson C. Davis's two brigade division of the XX Corps (no relation to Confederate President Jefferson Davis), marching north from Crawfish Springs. They attacked Col. Hans Heg's brigade on Davis's left, and forced it across LaFayette Road. Hood ordered Johnson to continue the attack with two brigades in line, one in reserve; the two drifted apart during the attack. During the afternoon fighting, Hood's and Johnson's men pushing strongly forward, approached so close to Rosecrans's new HQ at the tiny cabin of hte widow Eliza Glenn that the staff officers inside had to shout to make themselves heard over the battle outside. There was a huge risk of a Union rout at this part of the line. Wilder's men eventually managed to hold back the Confederate advance, fighting from behind a drainage ditch. The Union troops launched several unsuccessful counterattacks late in the afternoon to try to regain ground around the Viniard House. Col Heg was mortally wounded during one of these advances. Late in the day, Rosecrans deployed almost his last reserve, Maj. Gen. Philip Sheridan's division of McCook's corps. Sheridan took two brigades with him, and was successful in pushing out the Confederates from the Viniard Field, but Col. Luther Bradley was wounded in the attack.  Late afternoon maneuvers on both sides Late afternoon maneuvers on both sides

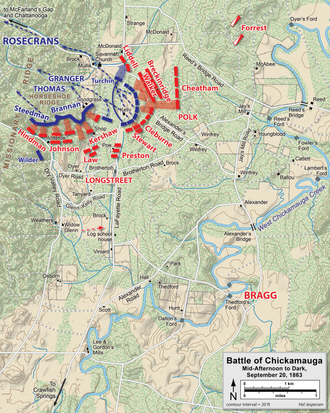

By 6 PM, the sun was setting, and Bragg had not abandoned his idea of pushing the Federal army south. He ordered Maj. Gen. Patrick Cleburne's division (from Hill's corps) to join Polk on their right flank. That area of the battlefield had been quiet for several hours as the fighting moved progressively southward. George Thomas had been consolidating his lines, withdrawing slightly to the west to what he considered a superior defensive position. Richard Johnson's division and Absalom Baird's brigade were in the rear of Thomas's westward moves, covering his withdrawal. At sunset, Cleburne launched an attack with three brigades in line - Brig. Gens. James Deshler, Sterling Wood, and Lucius Pol (left to right). The attack degenerated into chaos with the limited visibility of both twilight and the smoke from the burning underbrush. Some of Absalom Baird's men advanced to support Baldwin's Union brigade, but mistakenly fired at them, and were subjected to return friendly fire. Baldwin was shot dead from his horse while attempting to lead a counterattack. Deshler's brigade missed their objective entirely, and Deshler was nearly shot in the chest while examining ammo boxes. Brig. Gen. Preston Smith led his brigade forward to support Deshler, but mistakenly rode into the lines of Col. Joseph Dodge's brigade (Johnson's division), where he managed to shoot Dodge dead. By 9 PM, Cleburne's men retained possession of Winfrey Field, and Johnson and Baird had been driven back inside Thomas's new defensive line. The first day's casualties were difficult to calculate but somewhere around 8,000 Union and 5,000 Confederate would be reasonable. September 20

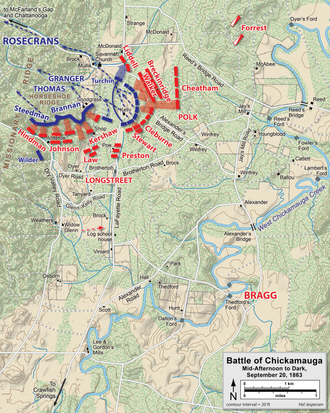

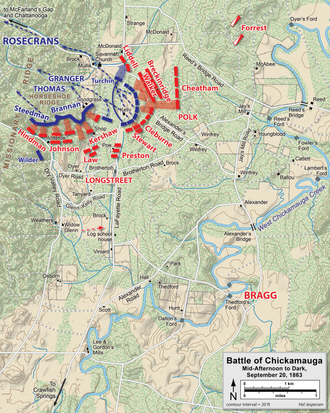

For the 20th, Bragg reorganized his army into two wings - right with Polk, and left with Longstreet.  Morning assault by Polk's wing Morning assault by Polk's wing

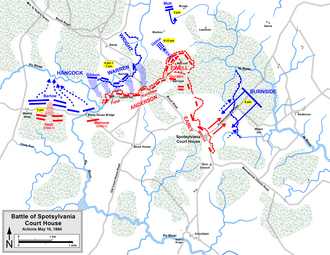

Fighting on the second day began about 9:30 AM, on the Union's left flank, about 4 hours after Bragg had ordered the attack to start, with coordinated attacks planned by Breckinridge and Cleburne from D.H. Hill's Corps in Polk's Right Wing. Bragg's intention here was for this to be the start of successive attacks progressing leftward along the Confederate line to try to drive the Union south, away from escape routes through the Rossville Gap and McFarland's Gap. The late start was significant. Bragg's aides reported that he believed had they not delayed, that would've been the moment they won their independence; at dawn, there was no defensive breastworks by Thomas's men. They were built a few hours after dawn. Breckingridge's brigades under Brig. Gens. Benjamin Helm, Marcellus Stovall, and Daniel Adams moved forward, left, and right in line. Helm's Brigade of Kentuckians made first ontact with Thomas's breastworks, and Helm (Abraham Lincoln's favorite brother-in-law) was slightly wounded while motivating his Kentuckians forward and removed from the field. Breckinridge's other two brigades did better against Brig. Gen. John Beatty's brigade from Negley's division, which was trying to defend a line more suitable for a division it was so wide. Once he found the Union's left flank, Breckinridge realigned his two brigades to straddle the LaFayette Road and then move south to threaten Thomas's rear. Thomas called up reinforcements to drive them back, and Adam's brigade was stopped by Col. Timothy Stanley's brigade. Adams got wounded, and was left behind as his men retreated from their position, and was later retrieved. The other part of Hill's attack also faltered. Cleburne's division met heavy resistance at the breastworks built that morning. Confusing lines of battle and overlap with Stewart's division to Cleburne's left diminished the Confederates' effectiveness in their attack. Cheatham's division, which was being held in reserve, couldn't advance either due to the troops in their front. Hill brought up Gist's Brigade, headed by Col. Peyton Colquitt to fill in the gap between Cleburne and Breckinridge. Colquitt was killed in the attack, and his brigade suffered severe casualties in their aborted advance. Walker brought up the rest of his division to rescue the survivors of Gist's Brigade. To his right flank, D.H. Hill sent Col. Daniel Govan's brigade to support Breckinridge, but the brigade had to retreat along with Stovall's and Adams's men faced with the Union counterattack. The Union attack on the Confederates' right flank petered out by noon, but caused a huge commotion throughout Rosecrans's army, as Thomas sent staff officers to get help from other generals along the line. Here Rosecrans dictated an order to Thomas to close up on Reynolds; the chief of staff, James A Garfield, was busy writing orders and didn't catch the error, as Frank Bond wrote the order instead, a person who was usually competent but inexperienced at writing orders. Wood was confused by the order, but when he spoke to corps commander McCook, he claimed later that McCook agreed to fill the gap with XX Corps units; McCook said he didn't have enough units to spare, though he did send Heg's brigade to partly fill the gap. On the other side, Bragg also made an order based on incomplete information. He was impatient that his attack wasn't progressing on the left, so he sent orders for all his commands to advance at once. Maj Gen. Alexander Stewart from Longstreet's wing got the order and advanced immediately without checking with Longstreet. Stewart's men disabled Brannan's right flank, and pushed back Van Cleve's division which was at Brannan's rear, momentarily crossing Lafayette Road. The Union counterattack to this drove Stewart's men back to their starting point. Longstreet got Bragg's order, but didn't attack immediately. He was surprised by Stewart's advance, and held up the order for the rest of his wing so that he could arrange his lines with his divisions from the Army of Northern Virginia in the front line, but this just resulted in the same kind of battle line confusion that Cleburne experienced earlier. When he was finally ready, he created a central striking force commanded by Maj. Gen. John Hood with three divisions in five lines. Longstreet's 10,000 infantry men were concentrated in a narrow column to try to break the enemy's line. Longstreet's after-action report showed he learned the effectiveness of the maneuver and would seek to emulate it later in the war.  Longstreet's mid-day Left-Wing assault Longstreet's mid-day Left-Wing assault

Longstreet gave the order to move at 11:10 AM, and Johnson's division proceeded across Brotherton field, by chance at the exact point where the Union division of Wood was pulling out of the line. The Confederates drove directly into the gap; the brigade to the right encountered opposition from Union troops but was able to push through. The result was soon a devastating rout of the Union Army. The few Union troops in that area of the field ran in panic from the onslaught. At the far side of Dryer Field, several Union batteries from XXI Corps (reserve artillery) were set up but had no infantry support. Gregg's brigade under Col. Cyrus Sugg flanked the guns on their right, capturing 15 of the 26 cannons on the ridge. As Union troops were withdrawing, Wood stopped his brigade, under Col. Charles Harker, and sent it back with orders to counterattack the Confederates. They had appeared on the scene on the flank of the Confederates who had captured the artillery, forcing them to retreat. Brigades under McNair, Perry, and Robinson got intermingled as they ran for shelter in the woods to the east. Hood ordered Kershaw's brigade to attack Harker, and raced towards Robertson's Brigade of Texans, which was Hood's old brigade. As he reached his former unit, a bullet struck him in his right thigh, hitting his artery and knocking him from his horse. He was taken to a hospital near Alexander's Bridge, but by the time the doctor got to him, he had bled out. Harker conducted a fighting withdrawal under pressure from Kershaw, retreating to Horseshue Ridge, near the tiny house of George Washington Snodgrass. Harker's men resisted several assaults there, since it was a good defensible position. The Confederates had no help from their fellow brigade commanders. On the Union side as the battle waged, Wilder sent the Assistant Secretary of War to Chattanooga; the time it took for him to do this wasted the opportunity for a successful attack, so Wilder ordered his men to withdraw. Union resistance at the southern end of the battlefield evaporated, and Sheridan's and Davis's divisions fell back to the escape route at McFarland's Gap, taking elements of Negley's and Van Cleve's divisions. The majority of units on the right fell back in disorder, and Rosecrans, Garfield, McCook, and Crittenden tried rallying their troops, but soon joined them in the mad rush to safety. Rosecrans decided to make haste to Chattanooga so that he could organize his men and the city's defenses. He sent Garfield to Thomas, with orders to take command of the forces remaining at Chickamauga and withdraw to Rossville. Sheridan decided to use a circuitous route to return.  Union defense of Horseshoe Ridge and Union retreat Union defense of Horseshoe Ridge and Union retreat

Luckily for the Union, not all of their Army had fled. Thomas still had four divisions holding their lines at Horseshoe Ridge. James Negley deployed artillery to protect his position on Kelly Field, and retreating men rallied in groups of squads and companies, erecting breastworks from felled trees. Units continued to arrive on Horseshoe Ridge, extending the line. Bushrod Johnson's division advanced on the western edge, threatening the Union flank, but fresh Union reinforcements had arrived. Through the day, the sounds of battle reached 3 miles north to Maj. Gen. Gordon Granger who proceeded without orders to send two brigades as reinforcements, but they were harassed by Confederate Maj. Gen. Forrest, causing them to veer west. Several more attacks and counterattacks shifted lines back and forth as the Confederates under Johnson got more and more reinforcements. Despite the furious action on the field, Longstreet was up enjoying a leisurely lunch of bacon and sweet potatoes with his staff in the rear. When he was summoned to a meeting with Bragg, Longstreet asked for reinforcements from Polk's stalled wing, even though he hadn't committed his own reserve, Preston's division. Bragg told Longstreet the battle was being lost, which Longstreet found inexplicable, but Bragg knew the successes at the southern end were just driving the Union to their escape route to Chattanooga, ending their chance to destroy the Army of the Cumberland. After repeated delays in the morning's attacks, Bragg lost confidence in his generals on the right wing, and denied Longstreet the reinforcements. Finally Longstreet deployed Preston's division, making several attempts to assault Horseshoe Ridge, starting about 4:30 PM. Longstreet later wrote there were 25 assaults in all on Snodgrass Hill. At the same time, Thomas got the order from Rosecrans to take command of the army and begin a general retreat. Thomas left, then Granger was placed in charge; when Granger left, no one was left to coordinate the withdrawal. Three regiments, the 22nd Michigan, 89th Ohio, and 21st Ohio, were left behind without sufficient ammo, and had to use their bayonets. They held until surrounded, at which time they surrendered to the Confederates. Command -US: William Rosecrans -CS: Braxton Bragg Army -US: Army of the Cumberland; 60,000 -CS: Army of Tennessee; 65,000 Casualties -US: 3657 killed, 13756 wounded, 4757 captured/missing; 22,170 -CS: 2313 killed, 9674 wounded, 1468 captured/missing; 13,455 Notable Casualties -US: William Lytle, George Crook*, Edward McCook*, Horatio Van Cleve* -CS: John Bell Hood* Almost Casualties -US: -CS: Brig. Gen. James Deshler*, Brig. Gen. Preston Smith*, Brig. Gen. Benjamin Helm* * indicates a change; a casualty that didn't otherwise occur or some other change in events. Battle of Chattanooga (Sept 21) After the victory at Chickamauga, the Confederates went northward to Chattanooga, and were able to besiege the city before Rosecrans could successfully set up his defensive works with men and artillery. Through inspired maneuvering with horse and artillery, the already exhausted Rosecrans gave up Chattanooga after ten hours of shelling from the Confederates, evacuating for Murfreesboro. It was this which cost him his command, as he was relieved by Grant and replaced with Thomas. The Secretary of War, however, interceded and got Major General John McClernand reinstated, despite misgivings from Grant, Sherman, and Admiral Porter, but he wouldn't arrive till November, letting Thomas begin refitting the army till then. Command -US: William Rosecrans -CS: Braxton Bragg Army -US: Army of the Cumberland: 42,000 fielded -CS: Army of Tennessee: 51,000 fielded Casualties -US: 2,198 wounded/killed -CS: 1,044 wounded/killed Proclamation 106 - A Day of ThanksgivingA Proclamation

The year that is drawing toward its close has been filled with the blessings of fruitful fields and healthful skies. To these bounties, which are so constantly enjoyed that we are prone to forget the source from which they come, others have been added which are of so extraordinary a nature that they can not fail to penetrate and soften even the heart which is habitually insensible to the ever-watchful providence of Almighty God.

In the midst of a civil war of unequaled magnitude and severity, which has sometimes seemed to foreign states to invite and to provoke their aggression, peace has been preserved with all nations, order has been maintained, the laws have been respected and obeyed, and harmony has prevailed everywhere, except in the theater of military conflict, while that theater has been greatly contracted by the advancing armies and navies of the Union.

Needful diversions of wealth and of strength from the fields of peaceful industry to the national defense have not arrested the plow, the shuttle, or the ship; the ax has enlarged the borders of our settlements, and the mines, as well of iron and coal as of the precious metals, have yielded even more abundantly than heretofore. Population has steadily increased notwithstanding the waste that has been made in the camp, the siege, and the battlefield, and the country, rejoicing in the consciousness of augmented strength and vigor, is permitted to expect continuance of years with large increase of freedom.

No human counsel hath devised nor hath any mortal hand worked out these great things. They are the gracious gifts of the Most High God, who, while dealing with us in anger for our sins, hath nevertheless remembered mercy.

It has seemed to me fit and proper that they should be solemnly, reverently, and gratefully acknowledged, as with one heart and one voice, by the whole American people. I do therefore invite my fellow-citizens in every part of the United States, and also those who are at sea and those who are sojourning in foreign lands, to set apart and observe the last Thursday of November next as a day of thanksgiving and praise to our beneficent Father who dwelleth in the heavens. And I recommend to them that while offering up the ascriptions justly due to Him for such singular deliverances and blessings they do also, with humble penitence for our national perverseness and disobedience, commend to His tender care all those who have become widows, orphans. mourners, or sufferers in the lamentable civil strife in which we are unavoidably engaged, and fervently implore the interposition of the Almighty hand to heal the wounds of the nation and to restore it, as soon as may be consistent with the divine purposes, to the full enjoyment of peace, harmony, tranquillity, and union.

In testimony whereof I have hereunto set my hand and caused the seal of the United States to be affixed.

Done at the city of Washington, this 3d day of October, A. D. 1863, and of the Independence of the United States the eighty-eighth.

ABRAHAM LINCOLN.

By the President:

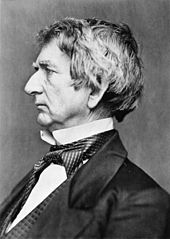

WILLIAM H. SEWARD, Secretary of State.

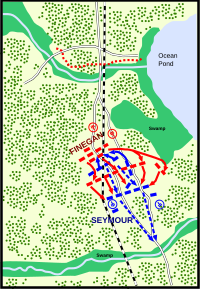

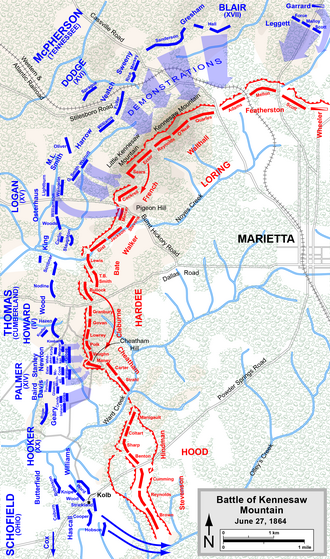

Subtle hints come through when Lincoln calls the southerners fighting for independence as 'perverse' and 'disobedient,' which then resulted in southern newspapers likening him to King George III, and non-London papers noting the hypocrisy of the US President fighting against the south just like they had fought against their own colonial forefathers. Battle of Bristoe Station (October 16-18)  Course of battle at Bristoe Station Course of battle at Bristoe Station

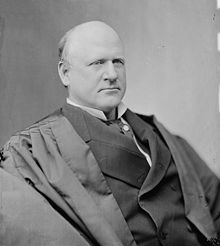

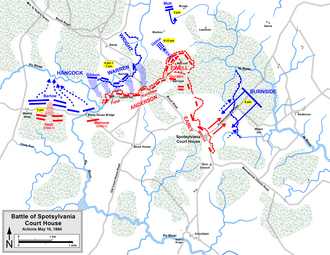

Union forces were led by Maj. Gen. George Meade, and the Confederates by General Robert E. Lee. Lee led his army around Cedar Mountain, forcing Meade to retreat towards Centreville. By withdrawing, Meade prevented Lee from coming on an exposed flank of his Army of the Potomac. Maj. Gen. Gouverneur Warren, in charge of II Corps, fought with J.E.B. Stuart's cavalry back on the 13th near Auburn, VA. Warren needed to retreat and push Stuart's men aside before Jackson's corps. On the 14th, Warren moved to Bristoe Station, where Stuart's Cavalry harassed his rear guard at the Second Battle of Auburn. Ewell, leading the Confederate Third Corps, was advancing on Jackson's left, reaching Bristoe Station on the 14th. Ewell tried engaging the rearguard of V Corps just across Broad Run, but missed the II Corps just coming up from Auburn. Seeing their advance, Ewell managed a rapid deployment of his forces behind the embankment of the Orange and Alexandria Railroad near Bristoe Station, resulting in a spectacular ambush as Ewell's corps moved to attack the Union's rear guard across Broad Run. Confederate Major General Henry Heth's division move to attack the Union V Corps, but redirected to attack II Corps. Union artillery, including a battery under Capt. R. Bruce Rickets, opened fire on the Confederates, with infantry joining in shortly thereafter. Despite this, Heth's men briefly secured a foothold, but were driven back, the Union capturing five of their guns. Col. Mallon was killed in the fighting. Maj. Gen. Richard Anderson's division attacked but was also repelled. Brig. Gen. Carnot Posey was wounded in the attack, and though it was a minor wound, infection set in and he died in November. Two of Heth's brigade commanders, William Kirkland and John Cooke, were wounded, but would return to active duty later. Warren saw Jackson's Second Corps coming up on the right, and had to withdraw. When the Confederates had to leave, they destroyed much of the railroad to deny it to the Union; the Union eventually rebuilt it. Command

-US: Gouverner Warren -CS: Richard Ewell Army

-US: Army of the Potomac, II Corps -CS: Army of Northern Virginia, Third Corps Strength

-US: 8,383 -CS: 17,218 Casualties

-US: 566 -CS: 988 Battle of Rappahannock Station (November 7) Part of a series of sparring matches between Meade and Lee, the battle at Rappahannock resulted in a lopsided win for the Union, which lost around 480 men, while the Confederates lost 1603 men, who were captured as POWs.

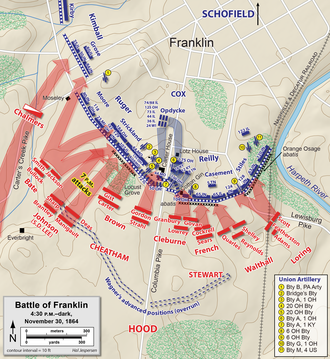

Battle of Campbell's Station (November 16) James Longstreet's men deployed first at the field at Campbell's Station, facing Union Major General Ambrose Burnside's men, who were delayed by the muddy rains. Longstreet managed a successful double-envelopment, which forced Burnside's withdrawal from the area. Battle of Fort Sanders (November 23) Longstreet pursued Burnside to Fort Sanders, where he successfully used the element of surprise, coordinating his artillery and skirmishers to force a defeat, and the withdrawal of Burnside, who left past Knoxville, and up to Bean Station.

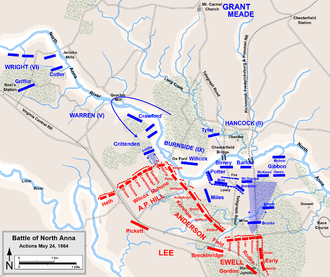

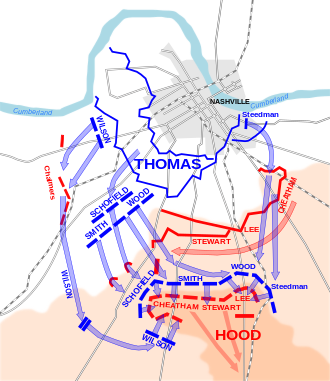

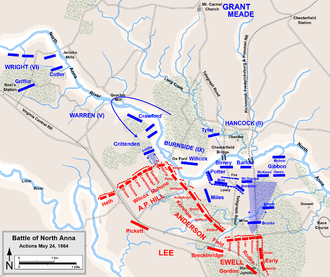

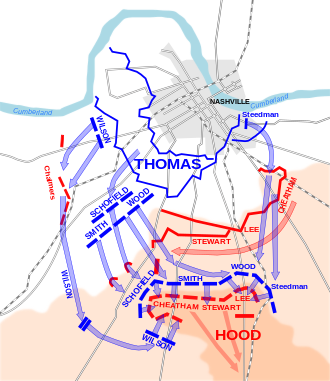

Battle of Chattanooga (November 23 to 25)  Bragg knew his siege was effectively broken when the cracker line reopened. He had options - retreat; assault the fortifications of Chattanooga; wait for Grant to attack; move around Grant's right flank; move around his left flank. The only promising option was to move around Grant's left flank, which would possibly allow him to re-establish another supply line to Virginia via Knoxville, and join forces with around 10,000 Confederates under the command of Maj. Gen. Samuel Jones, operating in southwestern Virginia. Unfortunately Burnside was currently occupying Knoxville, and blocking the railroad. He sent 11,000 men under Maj. Gen. Carter Stevenson to accomplish this, but Davis said he was sending Longstreet and his two divisions into East Tennessee, replacing the Stevenson/Jackson force.  Battles of Chattanooga, 24-25 November Battles of Chattanooga, 24-25 November

The first action was at Orchard Knob. On the 23rd, the Union saw Cleburne's and Buckner's men marching away from Missionary Ridge, and heard from some Confederate deserters that the entire army was falling back. Thomas ordered Brig. Gen. Thomas Wood's division to conduct a reconnaissance in force, and avoid engagement with the enemy, then return to the fortifications when they knew the strength of the Confederate line. Wood's men assembled outside the entrenchments, and observed their objective about 2000 yards away on Orchard Knob. Sheridan's division lined up similarly to protect Wood's right flank; Howard's XI Corps extended the line to the left, presenting about 20,000 troops. At 1:30 PM, 14,000 Union soldiers moved forward at the double quick, sweeping across the plain, stunning the 600 Confederate defenders, who were able to fire only a single volley before they were overrun. Casualties were relatively light; Grant and Thomas ordered their men to hold their positions and entrench, rather than withdraw, as was their original order. Orchard Knob became Grant and Thomas's HQ for the remainder of the action of Chattanooga. Mistakenly the Confederates couldn't decide whether to defend the crest or base, and the divisions of Brig. Gens. William Bate and Patton Anderson were ordered to move half their divisions to the base at the rifle pits there, the rest to the crest. Even worse, they were on the physical crest, not the military crest, handicapping the defenders. The Union also changed their plans; Sherman had 3 divisions ready to cross the river, but the pontoon bridge at Brown's Ferry had torn apart, and Brig. Gen. Peter Osterhaus's division was stranded over in Lookout Valley. After Sherman assured him he could do it with 3 divisions, Grant decided to allow the attack on Lookout Mountain, and moved Osterhaus to Hooker's command. November 24

Hooker had about 10,000 men in 3 divisions for his operation on Lookout Mountain. Hooker was ordered to "take the point only if his demonstration should develop its practicability." 'Fighting Joe' ignored the subtlety, and ordered the troops to "cross Lookout Creek and to assault Lookout Mountain, marching down the valley and sweeping every rebel from it." The men of Brig. Gen. John Brown's Confederate brigade on the mountain top found they were powerless to intervene in the battle below. The fighting continued between both sides, and by 3 PM, thick fog enveloped the mountain. The two sides fired blindly in the fog, but few men were hit. Hooker sent a stream of messages to Grant, one of which predicted the Confederates would evacuate in the night. Realizing the battle was lost, Bragg ordered his men to withdraw. As the fog cleared out about midnight, under a lunar eclipse, the divisions of Cheatham and Stevenson retreated behind the Chattanooga Creek, burning bridges behind him. That night Bragg asked his two corps commanders whether to retreat or fight; Hardee counseled retreat, Breckinridge convinced Bragg to fight it out on Missionary Ridge. November 25

Battle of Missionary Ridge Battle of Missionary Ridge