jjohnson

Chief petty officer

Posts: 144

Likes: 219

|

Post by jjohnson on Nov 7, 2019 17:17:59 GMT

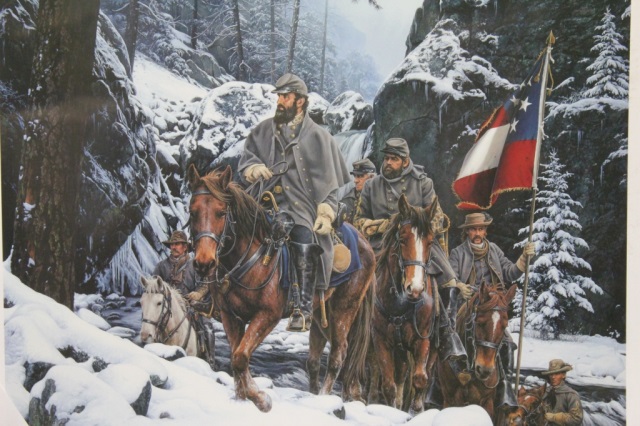

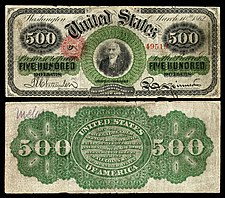

This will be a timeline exploring the rise of the Confederate States, and will continue the journey into the 21st century and beyond (which will make those posts sci-fi). The point of departure (PoD) will include: JEB Stuart an Stonewall Jackson surviving, the Cleburne Memorial becoming the basis for the emancipation law, and will show the effects of the loss of the south on the US as well. Please note that this will not include the all-too-common clichés of (a) the US conquering the CS completely, piecemeal, or partially to leave a 'rump CSA,' (b) the CS being an international pariah with segregation, horrid racism, etc continuing into the 21st century, (c) the CS falling apart into some kind of dictatorship, be it socialist, communist, or fascist. I will try to keep it realistic but then again, all alternate history is a form of unrealism. Also please note that I hate slavery, which should go without saying for anyone living in the 21st century. Events may happen that do not represent my own beliefs but may be what I thought was plausible given the split between the US/CS and the repercussions from that split. So here comes 'Dixie Forever.' Prologue: Some people in New England, on their legislatures and in their newspapers, threatened secession yet again after the end of the Mexican-American War. Four times before, in 1802-1803, in 1811-12, in 1814, and in 1844-45, people in the north threatened secession and this would make the fifth. First, Colonel Timothy Pickering of Massachusetts, friend of George Washington, of Massachusetts, and member of his cabinet; second from Josiah Quincy, another distinguished citizen of Massachusetts; third from the Hartford Convention of 1814; fourth from the Legislature of Massachusetts. Josiah Quincy, in the debate on the admission of Louisiana to the Union, on January 14, 1811, declares his “deliberate opinion that, if the bill passes, the bonds of this Union are virtually dissolved,…as it will be the right of all [the States], so it will be the duty of some, to prepare definitely for a separation, - amicably if they can, violently if they must.” In 1839, John Quincy Adams declared that “the people of each State have a right to secede from the Confederated Union.” In 1844, and again in 1845, the Legislature of Massachusetts reiterated its right to secede, and threatened to exercise that right if Texas were admitted to the Union: “The Commonwealth of Massachusetts, faithful to the compact between the people of the United States, according to the plain meaning and intent in which it was understood by them, is sincerely anxious for its preservation, but it is determined, as it doubts not the other States are, to submit to undelegated powers in no body of men on earth.” Not even the Oregon Treaty ameliorated the abolitionists and other New Englanders; President Polk wanted Texas, but agreed to a treaty with the United Kingdom, based on the existence of US settlers north of the 49th parallel, the existing border between the US and British North America. This new treaty gave the US all land west of the Continental Divide in the Rockies, and south of the 49° N parallel. Every time the United States acquired more territory it seemed as if New England threatened to secede. But it wouldn't be the North which would carry out the threat. This timeline is inspired by the Union Forever timeline from Mac Gregor, and Dominion of Southern America from Glen. I hope to make this as detailed and fun as his timeline is. -- Small History of Slavery in these United States: In the 1600s, indentured servants, from Ireland, Scotland, England, and Wales ventured over to the New World, working for 7 years, then when the indenture ended, they got land they were allowed to work. In the early 1620s, Africans came over with indenture and after seven years, were also freed to work their land. In Massachusetts, however, the Puritans enslaved the Indians they found, and when they proved not fit for slavery, the Puritans brought Africans. In 1637, the slave trade was legalized in Massachusetts, and in 1641, slavery. It would be 1655 before slavery was legalized in Virginia, and then by the court first, when Anthony Johnson, a free African from Angola, sued to regain John Casor, another African whose indenture had already expired. The court ruled in his favor, and Casor became the first African whose labor was owned for life. Over time, the northern and southern colonies would both have slavery. Rhode Island merchants began importing Africans in 1652. In 1703, 42% of people in New York City owned a slave, and many famous families in New England would grow rich in the slave trade - Faneuil (of Faneuil Hall fame), Royall, and Cabot from Massachusetts, Brown (the family which founded the University), Wanton, Champlin (Rhode Island), Whipple from New Hampshire, Easton from Connecticut, Willing and Morris from Philadelphia. Ezra Stiles imported slaves while President of Yale, six mayors of Philadelphia acted as slave merchants at the same time. Prominent slave traders, when they returned home, would stake a pineapple on their property as a sign they were open for business, which over the years since has become a mere decorative symbol. Before 1830, 4 of every 5 abolition societies were located in the southern colonies/States. Georgia banned slavery in 1735, but a royal decree in 1751 authorized it. Virginia petitioned the king in the 1750s and 1760s to stop importation of slaves but was ignored. During this time slaveholders in the south voluntarily freed slaves either upon their death or by allowing them to purchase their freedom. Unfortunately things grew harsher after the rebellion in Haiti, which began the laws against teaching reading and writing to slaves. In 1831, Virginia nearly banned slavery, missing the mark by 4 votes, only failing due to the failed Nat Turner rebellion*. -- Settlement of North America: The settlers in New England were Pilgrims (separatists) who wanted a separate church from the Church of England, and Puritans, who wanted to purify the Church of England to make it more Protestant. The Puritans viewed themselves as a city on a hill, and very exclusionary. If you didn't agree with them, they would throw you out, which is how Connecticut, New Hampshire, and Rhode Island came about. The settlers of New England came mostly from East Anglia and traditionally English areas of Britain. They viewed conformity with the group as a high moral cause, which would influence their political development for centuries to come. Their 'city on a hill' talk showed their belief in their own righteousness, a self-absorbed, holier-than-thou attitude that looked down on the rest of the colonies and states if they didn't agree with their views on things. In viewing their writings, you could see the New England attitude of nature as dark and foreboding, something to be conquered, controlled, and tamed. Over time, northerners drifted from their Christian roots, despite several 'Great Awakenings,' with Unitarianism, a heretical belief to orthodox Christianity, growing in popularity, along with various European intellectual movements, leading to a lot of secular humanism, atheism, deism, transcendentalism, and eventually socialism and Marxism, essentially any philosophy that looked to man for salvation and for values, rather than to God. New Englanders viewed themselves and their 'pure' English heritage as the only true Americans, looking down at the mixed South, with its Celtic, English, German, American Indian, Black, Hispanic, and African people and cultural influences on each other as polluted. Southerners (Maryland through Georgia) tended to come from Northern England, Scotland, Northern Ireland, and more Saxon areas of England. Theirs was the cavaliers, a paternalistic culture that was individualistic, as opposed to the New Englanders. Southerners had a more relaxed life, viewing nature as worthy of embrace and enjoyment, a gift from God, and a paradise. The cavaliers worked hard on their plantations, but they didn't like being seen working or handling money, leaving northerners to view them as lazy. As the North grew secular, the South entrenched into its orthodox religion. It looked to God for guidance via prayers and viewed the secular humanism of the north with suspicion and hostility. Baptist and Methodist churches sprang up all over and literal biblical preaching gained thousands of converts. Middle Colonies (New York, Pennsylvania, New Jersey, Delaware) were more often Quakers and came from the northern Midlands of England, and often had more in common with southerners than the New Englanders. -- Small history of sectionalism in these United States: During the votes on the Constitution in 1787, Hamilton advocated what amounted to an elected monarchy, and for reducing the states to nothing more than counties of a federal government, a plan which was rejected by the committee. The Articles of Confederation acknowledged the independence and sovereignty of 13 sovereign nations (States in 18th century parlance means the same thing), and the new Constitution would do so tacitly until the 10th amendment was added. A number of southerners, however, warned against confederating with northerners, but the south compromised and joined with them, despite their cultural differences already apparent in the 1780s and 1790s. By the 1820s, northerners who had grown used to protective tariffs had succeeded to getting a new high tariff to protect their industries passed, which caused a crisis, where South Carolina threatened nullification and even secession. To preserve the Union, however, the tariff was lowered, but New Englanders were fuming, as this affected their pocketbooks, so they thought to affect southern pocketbooks and attack them where they were vulnerable - slavery. Every fight from the northern perspective would now be a fight 'against slavery' to get what they wanted, namely protectionism and more central control, later called 'the American System' by Henry Clay, who would become Abraham Lincoln's political idol. The Missouri Compromise in 1820 involved sectionalism, with northerners not wanting Missouri as a slave state, because southern Democrats would be carrying slaves there, meaning another state which would vote against their northern interests. The south, desiring to preserve the Union, agreed to limiting slavery south of the 36°30' line, giving up a large part of the country to their plantation-style of agriculture for the sake of harmony; truth be told, most of the rest of Missouri Territory wasn't fit for plantation-style agriculture, but northerners wanted that territory for white people and white immigrants, as Abraham Lincoln would later admit, when he said that he intended western territory for white people. From the 1830s to the 1860 election, more and more sectional hatred was engendered by the Whigs, and later the Republicans, with the Mexican-American War opposed by some in the north who claimed it was a conspiracy to expand slavery; the negotiations short-changed the territorial ambitions of some who didn't want to expand southern states, who would then be settling those new states and could possibly out-vote the northerners. Far from any moral outrage, most anger in the north was about the same thing as always - money and power. During the debates on the passage of the Constitution, Patrick Henry said in 1787, " Those who have no similar interest with the people of the South are to legislate for us. Our dearest rights are to be put in the hands of those whose advantage it will be to infringe them. They will rule by patronage and sword. The states are committing suicide." *Vote total different from our timeline (OTL) Violence in the Senate

In 1856, on the 19th-20th of May, Massachusetts Senator Charles Sumner spoke on the floor of the Senate. He was an illusion of moral character to the people of the North, most especially in New England, and counter to the traditional black frock coats other wore, he wore a light-colored English tweed coat with lavender trousers, looking like a vain fop. His speech showed his character, acting like a classical scholar schooling slow and dim-witted children, insulting specifically two Democrat Senators, namely Senator Stephen Douglas of Illinois, who was present in the chamber with maybe a handful of other Senators, but also Senator Andrew Butler of South Carolina, an elderly, sickly Senator who wasn't even present. Those five hours covered a lot of mockery of Butler's supposed southern chivalry, and likened slavery to prostitution, "a mistress...who though ugly to others, is always lovely to him; though polluted in the sight of the world, is chaste in his sight." At the end of his invective-filled speech, Senator Douglas rose to defend himself and Butler, who wasn't even there. Representative Preston Brooks of South Carolina was there, and read his speech, wanting to challenge Sumner to a duel. Brooks's friends told him Sumner wasn't a gentleman, and any duel between them would lack honor, so Brooks chose a "light cane of the type used to discipline unruly dogs," and went to the Senate Chamber. A few days later on the 28th, the Senate report included his words: “‘… I desire my friends to understand what I have done, and why I did it. Regarding the speech as an atrocious libel on South Carolina, and a gross insult to my absent relative, I determined, when it was delivered, to punish him (Sumner) for it. Today I approached him after the Senate adjourned, and said to him, ‘Mr. Sumner, I have read your speech carefully, and with as much calmness as I could be expected to read such a speech. You have libeled my State and slandered my relation, who is aged and absent, and I feel it to be my duty to punish you for it’; and with that I struck him a blow across the head with my cane, and repeated it until I was satisfied. No one interposed, and I desisted simply because I had punished him to my satisfaction.” Contrary to fevered newspaper reports, Sumner was confronted, not snuck up on. Sumner in southern eyes, exemplified the perennial intellectualist politician spreading a mass of loose, bitter-toned hatred for his political opponents that turns so many off to politics. Commentaries on the Constitution

Abel Upshur: "I venture to predict that if it [the federal government] will beome absolute and irresponsible, precisely in proportion as the rights of the States shall cease to be respected, and their authority to interpose for the correction of federal abuses shall be denied and overthrown." St George Tucker: Blackstone's Commentaries : with notes of reference to the constitution and laws, of the federal government of the United States, and of the Commonwealth of Virginia Abel Upshur: A Brief Enquiry into the Nature and Character of our Federal Government William Rawle: A View of the Constitution of the United States of America (Second Edition) These three works by men who fought in or lived at the time of the American Revolution all indicated a widespread belief in the constitutionality of secession and that the Constitution was a compact between "free, independent, and sovereign" states. James Madison, responding to Daniel Webster's assertion of "one people" creating the Constitution: " It is fortunate when disputed theories can be decided by undisputed facts. And here the undisputed fact is that the Constitution was made by the people, but as embodied into the several States who were parties to it, and therefore made by the States, in their highest authoritative capacity...The Constitution of the United States, being established by a competent authority, by that of the people of the several States..." It was a common belief at the time that there was no 'one nation, indivisible,' but rather that the United States were a republic of republics. Socialism and Communism

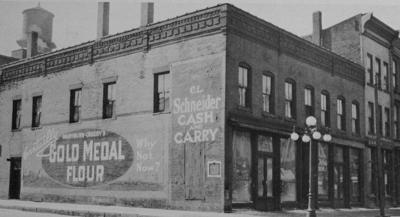

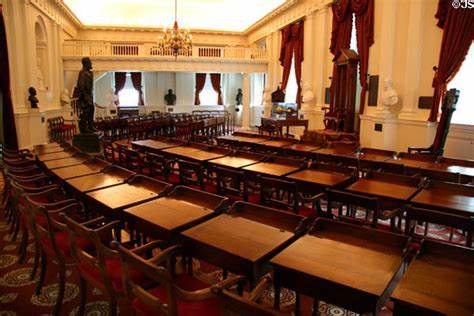

Friedrich Engels, co-founder of Marxist Communism, wrote to future Union General Joseph Weydemeyer, about the aim of consolidating small republics into one large indivisible republic. He wrote: "The preliminaries of the proletarian revolution, the measures that prepare the battleground and clear the way for us, such as a single and indivisible republic, etc...are now convenu [taken for granted]." Weydemeyer was a fellow communist, who with Charles Dana, Marx's friend and future assistant secretary of war, got the first copies of the Communist Manifesto printed in the United States. Engels knew in 1848 that as long as governments were close to the people in small republics, it would be difficult to impose communism. All the revolutions in 1848 had been defeated. But in Lincoln, his first inaugural address denied that the states were sovereign, claiming instead that the confederated Union government was sovereign over the states. Many of the '48-ers, as they were called, from Germany, would leave Germany and come to the northern United States and attempt their revolution again in the United States, to consolidate the smaller republics (States) into a larger republic (the Federal Government). Abraham LincolnThough Abraham Lincoln would convey the image of a humble rail-splitter and a common man's lawyer, that was far from the truth. From the start of his professional career, he was a Whig, and he idolized Henry Clay. The Whig Party was the party of big business back in its day, the party of big government, for the time. The party was the spiritual successor of the old Federalist Party of Adams and Hamilton, and in its new guise sought 'bounties' (subsidies) for businesses for internal improvements (railroads, canals, roads) and to fund those, a high protective tariff, which would also conveniently protect the New England industries from foreign competition, despite their products often being inferior to English goods, and with the tariff, they could inflate their prices more to pad their pockets. Around 1835-36, Lincoln wrote a book on his views on religion, called Infidelity. The work was read by his friend, Mr Hill, but before he could burn it, another friend of his found the work and substituted it for another the same size, which Hill then burned, believing it to be Lincoln's book. In the book, Lincoln denied the miraculous conception of Christ, ridiculed the Trinity, and denied the Bible was the divine special revelation of God. Hill believed he burned it, and counseled Lincoln not to speak of such things ever again. Thereafter, Lincoln would be very guarded about his religious views, though his closest friends would know he was a 'free thinker' or an infidel, as they called it in the day. During the Mexican-American War, Lincoln was a representative in the US House, his only term there. But he liked being near the power center. He didn't make too many friends in the House, and when he made his speech on the floor of the House about "show me the spot where Mexico invaded our land," he earned the nickname "Spotty Lincoln" thereafter till he left the House. Lincoln was also a railroad lawyer, noticed by the Illinois Central Railroad in 1851 when he defended a small local railroad in front of the Illinois Supreme Court. So they took him on to defend them, and as one of the perks, they gave him an annual pass, which allowed him to travel on their railroad for free, and as much as he wanted. By the time of his election as President, Lincoln had collected more in lawyer's fees from ICR than any other client. One of the ICR's engineers, Grenville Dodge, an acquaintance of Lincoln's, suggested he purchase some land over at Council Bluffs, Iowa. That land would happen to be the future eastern end of the transcontinental railroad. While President, Lincoln pushed a bill through Congress to begin the construction of the Union Pacific Railroad, which conveniently began at...Council Bluffs, Iowa. When his acquaintance, Dodge, volunteered for service in 1861, he quickly rose to Major General in the Army and became the Chief Engineer for the construction of that Union Pacific Railroad. Today that would be considered insider trading. In 1856, Lincoln gave a speech for the Republicans that he refused to write down, but several members of the audience took detailed notes, and it would later be written down in 1865 from those notes* after the war. At Major's Hall in Bloomington, Illinois, he revved the crowd into a fevered frenzy the likes of which any wildly gesticulating dictator-demagogue from central Europe would envy.  Major's Hall, Bloomington, IL Major's Hall, Bloomington, IL

Lincoln whipped up the crowd with claims that the southern states were going to make poor white men into slaves, things, just as they thought blacks were things, despite laws in the south at the time separating the person from the labor, according to southern politicians at the time. He made reference to his belief in white supremacy, "Nor is it any argument that we are superior and the negro inferior —that he has but one talent while we have ten." to the applause of the audience. He referenced poor Sumner in the Senate getting caned, calling it 'being murdered,' while ignoring Sumner spending five hours in the Senate insulting one of the members and his State, which, by the culture of South Carolina, deserved an answer, thinking he could get away with any insult without consequence. He called the South violent in repealing the Missouri Compromise (despite it being a relatively civil vote in Congress), while ignoring northern violence of 'Beecher's Bibles,' disguised rifles intended to be used to kill any southerner or southern sympathizer so Kansas would become a state dominated by northern settlers, and John Brown's northern-funded murder spree in the territory. His speech then delved into his own strange mish-mash of history, where he theorized the Articles of Association from 1774 are the legal creation of the United States, despite them being nothing of the sort, but rather a 'non-importation' promise if the King didn't resolve the issues experienced by the 13 colonies (Georgia didn't participate at the time). Ironically, he said that "It is, I believe, a principle in law that when one party to a contract violates it...the other party may rescind it." That same argument was claimed by the South against the North due to their pursuance of 'liberty laws,' by which they nullified part of the Constitution, which should have required an amendment. While he did to his credit condemn slavery as wrong and evil, as anyone today would agree, his demagoguery whipped everyone into such a frenzy that compromise would soon become impossible. *The speech is real, but no one ever wrote it down, as they claimed they were caught up in the emotion of the speech. |

|

jjohnson

Chief petty officer

Posts: 144

Likes: 219

|

Post by jjohnson on Nov 7, 2019 17:24:36 GMT

Prologue 2: Rising Tensions

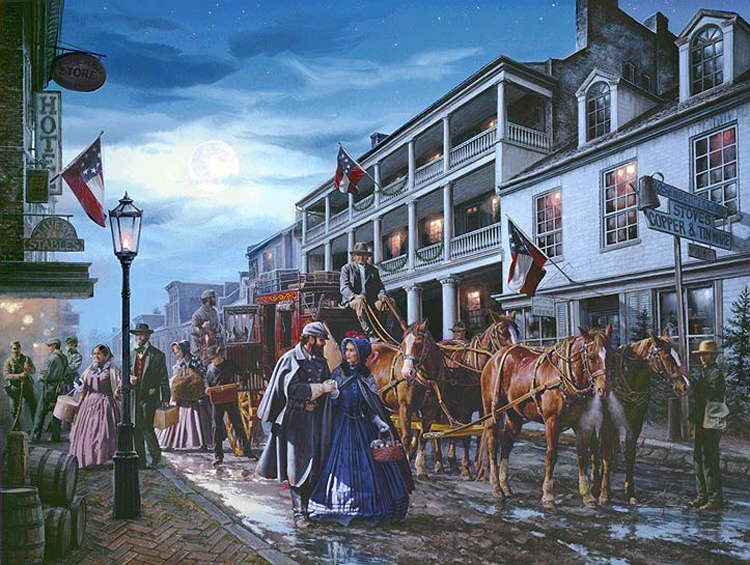

The 1850s were a time of growth but a time of increasing sectional tensions between the two great regions of the united states. The North and South grew increasingly at odds, while the Midwest tended towards siding with the North.

Harriet Beecher Stowe, an abolitionist, wrote Uncle Tom’s Cabin in 1852, spurring northern abolitionists against slavery. Other books concerning slavery, A Southside View of Slavery (Nehemiah Adams), and American Slavery As It Is (Theodore Weld and the Grimké Sisters) gave a picture of slavery as practiced in the south as well, but were not best-sellers like Stowe’s book. James Redpath's book The Roving Editor condemned the South and encouraged a Haitian-style slave revolt involving mass murder of Southern whites. That, along with Uncle Tom's Cabin and The Impending Crisis in the South began to give southerners the feeling they were personally threatened by the sentiment of an entire section of the country. Redpath's book had the following dedication to John Brown, the man who murdered innocent people in Kansas, who held no slaves, but were guilty for simply being southerners, "You went to Kansas... not to 'settle' or 'speculate' or from idle curiosity: but for one stern, solitary purpose - to have a shot at the South!"

Senator Lewis Cass proposed the idea of ‘popular sovereignty,’ wherein a territory would determine whether it would have slavery, as Congress did not have that power enumerated in the Constitution. Northern Democrats called for ‘squatter sovereignty’ while Southern Democrats wanted the issue decided at statehood. After being defeated in 1848, Illinois’s Senator Stephen Douglas became a leader in the party with regard to popular sovereignty in his proposal of the Kansas-Nebraska Act.

This Kansas-Nebraska Act explicitly repealed the Missouri Compromise, and had the transcontinental railway run through Chicago, while organizing (opening for settlement) the territories of Kansas and Nebraska.

Gold had attracted settlers to California in 1848, with northerners and southerners hoping to make a new state for their region of the country. Southerners tried creating farms and plantations, and brought their slaves to the mines, while northerners wanted the state free and free of slaves. Rising tensions and small conflicts between the two centers of power – San Diego and Sacramento nearly resulted in the split of the state.

Without gold, the southwest, notably New Mexico and what would become Arizona would have their status determined by popular vote by the Compromise of 1850, while DC would abolish the slave trade, but not slavery, and a Fugitive Slave Law would help pacify the south.

The nation sent Commodore Matthew Perry to Japan in 1853 to help open up trade to the island nation, and a Pacific railroad was planned to bring both coasts together.

When Kansas was opened, the small-scale skirmishing from California repeated itself even more. Abolitionists from New England poured in to Topeka, Lawrence, and Manhattan, while pro-slavery settlers, mainly from Missouri, settled in Leavenworth and Lecompton. At the same time, southerners began settling en masse in a swath across the southernmost territories with their slaves, eager to try to make up their deficiency in numbers in the House with representation in the Senate by organizing the territories.

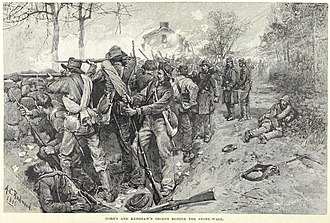

In Kansas, in 1855, the territorial legislature held elections. While there were only 1500 eligible voters, Missourians had swelled the population to 6000. A pro-slavery majority was elected, but the free-soilers were so outraged they set up their own delegates in Topeka. Anti-slavery Missourians sacked the settlement of Lawrence in May of 1856, and violence continued for another two years till the promulgation of the Lecompton Constitution. The conflict enflamed tensions back east. John Brown, a man of dubious mental health, was funded in going to Kansas to murder southerners to try to turn the tide in Kansas against the settlers with slaves.

Senator Charles Sumner (MA) gave a speech he called ‘The Crime Against Kansas,’ a scathing criticism of the South and slavery, wherein he attacked Senator Butler of South Carolina personally. Days afterward, Representative Brooks, also from South Carolina and a relative of Butler’s, caned Sumner for the insult to his family honor. Senator Stephen Douglas, who was also a subject of criticism during the speech, suggested to a colleague while Sumner was orating that "this damn fool (Sumner) is going to get himself shot by some other damn fool."

After the failure of the Whig Party in the last election, the remnants of the party reorganized into the Republican party, still focused on internal improvements funded by tariffs, central banks, along with railroads, free land for white farmers, and stopping the spread of slavery.

In the election of 1856, the Democrats nominated James Buchanan; the Know Nothings nominated former president Millard Fillmore; the new Republicans nominated John Frémont, who nearly won. The state of Southern California was comfortably for Buchanan. In the south, Frémont’s party was denounced as threatening civil war as a divisive force. Buchanan won 176-116, with Fillmore getting 8 electoral votes.

Shortly after his inauguration, on March 6, 1857, the Supreme Court released the Dredd Scott decision. They quickly ruled the obvious – that slaves were not US citizens and had no right to sue in court. The ruling also stated that since slaves were considered private property, their masters could reclaim runaways even from states where slavery did not exist, since the 5th Amendment forbade Congress to deprive a citizen of his property without due process. To add to their decision, the Supreme Court stated the Missouri Compromise was always unconstitutional and Congress couldn’t restrict slavery within a territory.

Southerners were emboldened with this decision, while Northerners were outraged, claiming a ‘slave power’ conspiracy controlled the Supreme Court. Anti-Slavery speakers protested the Supreme Court could only interpret law, not make it, so the decision couldn’t open a territory to slavery. The Republicans in the north would be emboldened by this decision for their next presidential election.

During his presidency, Buchanan noted that “The South had not had her share of money from the treasury, and unjust discrimination had been made against her.” Most moneys from the treasury had gone to fund internal improvements in the North, with little to no internal improvements being made in the South, even though the southerners, being mainly agricultural, paid the majority of tariffs. Foreign goods were more expensive since the South had less manufacturing, while the northern industry was protected by those same tariffs.

Horace Greeley, editor of the New York Tribune, told a fellow Republican in 1858, "I do not believe that the People of the Free States are heartily Anti-Slavery. Ashamed of their subserviency to the Slave Power they may well be; convinced that Slavery is an incubus and a weakness, they are quite likely to be; but hostile to Slavery as wrong and crime, they are not, nor (I fear) likely soon to be."

Meanwhile, in Illinois, a former Whig Congressman, now railroad lawyer, Abraham Lincoln, had a series of debates with Senator Stephen A Douglas, the incumbent, for 1858. Neither candidate for the Senate came out for equality between the black and white races, a common belief at the time. While Douglas would win the Senate seat, Lincoln would return to politics in 1860.

The debate over slavery heated up even more with the raid by John Brown on Harper’s Ferry in Virginia the next year. John Brown, receiving arms and money from Massachusetts business and social leaders, went into Virginia to create a slave army to sweep through the South, killing slave owners and liberating slaves. Local slaves did not rise up to support him as he expected, and he was captured by an armed force under Lt Colonel Robert E Lee. He killed 5 civilians, took hostages, and even stole the sword that Frederick the Great gave George Washington. To provide security during his execution, Virginia’s governor sent Thomas Jackson, a veteran of the Mexican War, with a group of VMI cadets, who stood at the scaffolding’s foot.

Divisions and Mistrust

The mistrust and antagonism of the two parts of the United States was summarized by Sam Watkins of Columbia, Tennessee: "The South is our country, the North is the country of those who live there. We are an agricultural people; they are a manufacturing people. They are the descendants of the good old Puritan Plymouth Rock stock, and we of the south from the proud and aristocratic stock of Cavaliers. We believe in the doctrine of State rights, they in the doctrine of centralization."

The South was a region steeped in traditions, including its religion, and was quite comfortable with the established frameworks of its civilization, while the Northern region was, in the view of the South, flitting between every new idea that came to its shores, moreso since the '48-ers from Europe came over with various new ideas on government that took hold up North. The Garrisonian Northampton Association, Frances Wright's Nashoba, and the Raritan Bay Union of Theodore Weld all tried to demonstrate what was called Christian Communism up North, something that found no takers in the more traditional South. Places like New Harmony, Indiana, founded on communist ideas, demonstrated the fascination such ideas had in the North.

Robert Lee's Views on Slavery and Abolition

During this decades's troubles, Robert Lee wrote on December 27, 1856 in a letter:

"There are few, I believe, in this enlightened age, who will not acknowledge that slavery as an institution is a moral and political evil in any country. It is useless to expatiate on its disadvantages. I think it a greater evil to the white than to the black race."

In the same letter:

"While we see the course of the final abolition of human slavery is still onward, and give it the aid of our prayers, let us leave the progress as well as the results in the hand of Him who sees the end, who chooses to work by slow influences, and with whom a thousand years are but as a single day."

"Although the Abolitionist must know this - must know that he has neither the right nor the power of operating, except by moral means; that to benefit the slave he must not excite angry feelings in the master; that, although he may not approve the mode by which Providence accomplishes its purpose, the results will be the same; and that the reasons he gives for interference in matters he has no concern with holds good for every kind of interference with our neighbor, - still, I fear he will persevere in his evil course."

Like many people of his era and of Virginia, Lee was in favor of abolition, but not sudden, but rather gradual, so that everyone can grow accustomed to the new independence of the former servants and make them capable and independent citizens.

|

|

jjohnson

Chief petty officer

Posts: 144

Likes: 219

|

Post by jjohnson on Nov 7, 2019 19:53:32 GMT

Chapter 1With the rising tensions, the 1860 election was a portend of things to come. If the Democrats had remained united, perhaps they could've won the election, but that is a matter for speculative fiction. Had it happened, perhaps states in the south might not have seceded. In Charleston, the Democrat National Convention took place, despite it being normally held in the North. The convention endorsed 'popular sovereignty,' which resulted in 50 delegates from the south walking out. When the convention delegates couldn't agree on a nominee, a second meeting then took place in Baltimore, Maryland. The party was fracturing. After the walk-out, the remaining Democrats nominated Senator Stephen Douglas, who had held a series of famous debates with the Republican candidate, Abraham Lincoln. Southern Democrats held a separate convention over in Richmond, Virginia, where they nominated the current Vice-President, John C Breckinridge as their candidate, with both sides claiming to be the true Democrats. In addition to this split, members of two former parties, the Know Nothings, and some Whigs, formed the Constitutional Union Party, which tried to avoid the sectional issues plaguing the republic by running on a platform of supporting the Constitution and the laws of the land and being against secession, while avoiding the issue of slavery altogether. The Republican National Convention met up in Chicago, taking a number of ballots to choose their nominee. William Seward won the first two ballots, but it had become apparent to many that he had alienated some branches of the party, and on the third ballot, a little known former representative, Abraham Lincoln, won the selection with a number of techniques practiced for decades and would continue to be used for decades to come - packing the crowd, not letting other candidates' supporters in, promises of money and cabinet positions. While the Democrats had fractured into three separate factions, the Republicans were unified, allowing them to gain the most votes in the electoral college, while gaining only 40% of the popular vote. Thomas Prentice Kettel, a noted economist of the era, wrote:

It [the North] had before it a most brilliant future, but it has wantonly disturbed that future by encouraging the growth of a political party [Republican] based wholly on sectional aggression, - a party which proposes no issues of statesmanship for the benefit of the whole country; it advances nothing of a domestic or foreign policy tending to national profit or protection, or to promote the general welfare in any way.

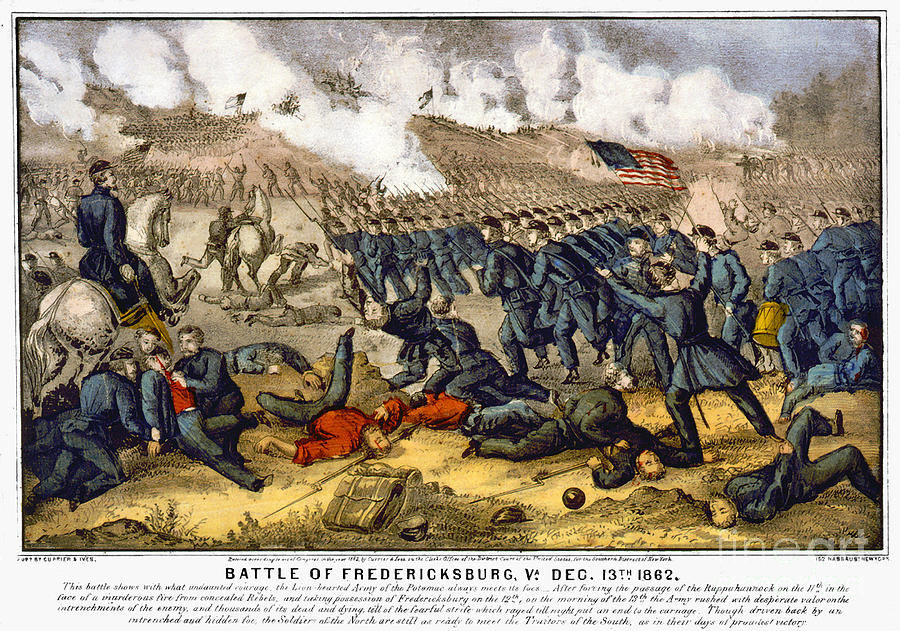

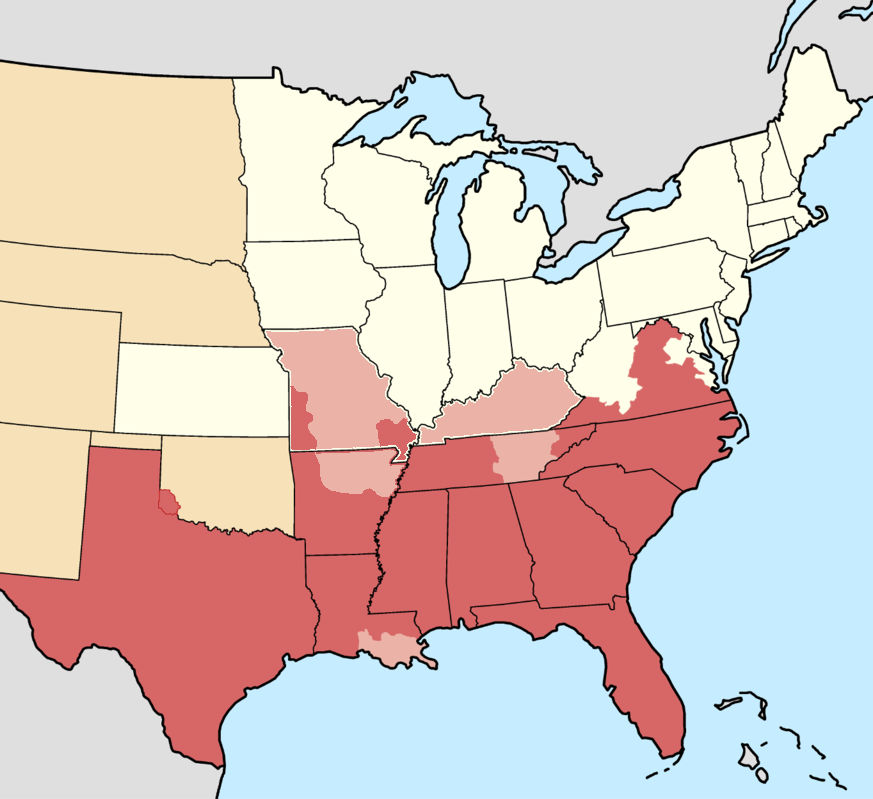

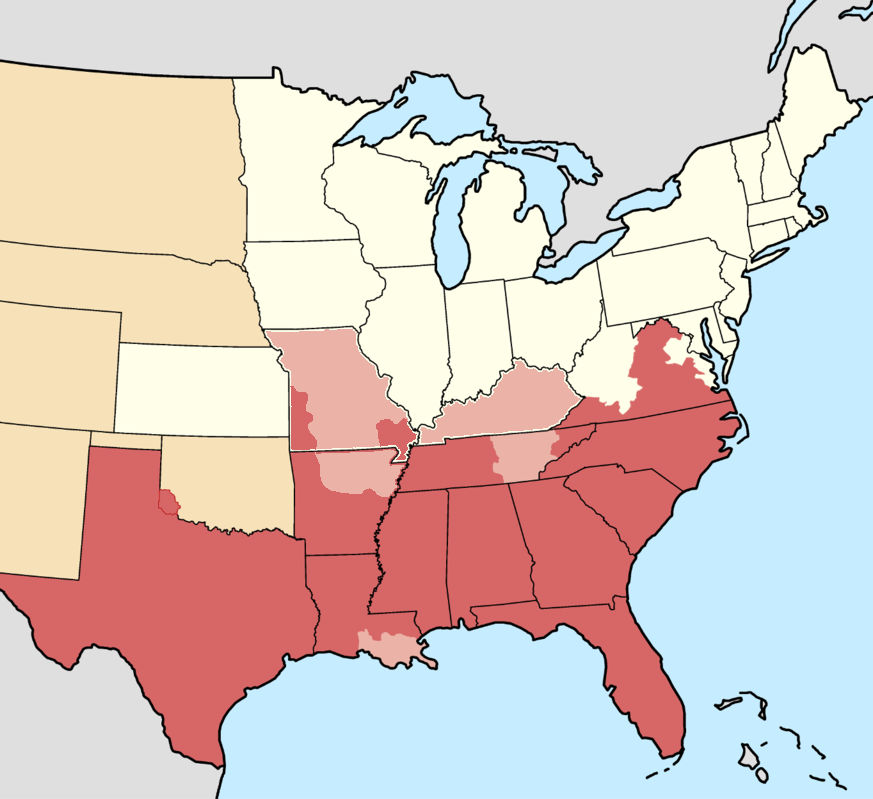

He later wrote of the hate used to rally northern votes in the 1860 election: The North has for more than ten years constantly allowed itself to be irritated by incendiary speakers and writers, whose sole stock in trade is the unreasoning hate against the South that may be engendered by long-continued irritating misrepresentation. Electoral totals: 180: Abraham Lincoln, Republican (red) 72: John Breckinridge, Southern Democrat (green) 39: John Bell, Constitutional Union (orange) 12: Stephen Douglas, Northern Democrat (light blue) 152 required to win. *NOTE: Map is edited from a modern QBAM. Gray are areas which remain territories at 1860. Lincoln's Measures

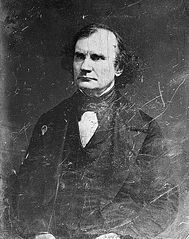

Lincoln's former law partners, who would become his biographers, Nicolay and Hay, wrote of him: " When the President determined on war, and with the purpose of making it appear that the South was the aggressor, he took measures..." On the 21st of December, Lincoln wrote of those measures in a 'confidential' letter to Elihu Washburne: " Please present my respects to the General (Winfield Scott), and tell him, confidentially, I shall be obliged to him to be as well prepared as he can to either hold, or retake, the forts, as the case may require, at, and after the inauguration." Mrs. Davis's Premonition

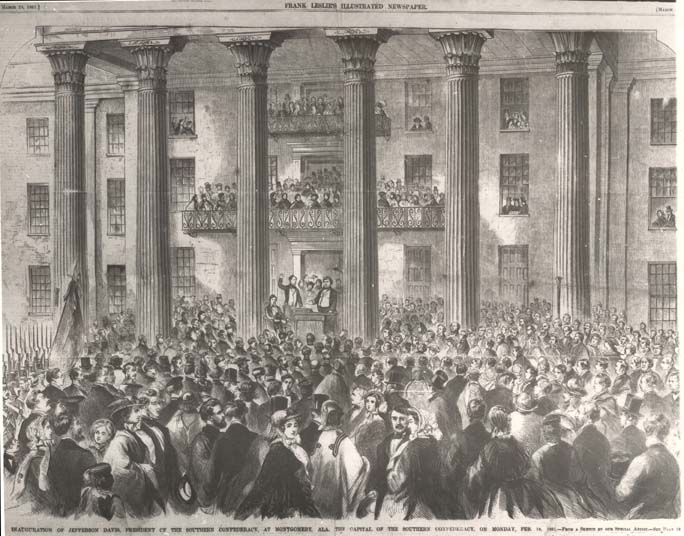

Speaking to one of her friends, and written down by diarist Mary Boykin Chesnut, Varina said "The South will secede if Lincoln is made president. They will make Mr. Davis President of the Southern side. And the whole thing is bound to be a failure." While she was in DC with her husband as a representative, she was known to have some 'unorthodox' views for the 1840s, such as "slaves were human beings with their frailties" and that "everyone was a 'half breed' of one kind or another." She joked she was a half-breed, with part of her family in the North and part in the South.  Varina Davis, 1849Secession Varina Davis, 1849SecessionSoutherners looked at the Republican party with fear. Many saw their victory as a sectional minority intent on overrunning them with tariffs and centralizing power in Washington, DC, away from the states. Once the election of Lincoln was certified, the people of several southern states voted regarding secession to protect their sovereignty from the centralizing party, which at this point in history was the Republican party. Missouri and Arkansas voted against secession at this point, as did Tennessee and North Carolina. The talk of secession was in the air. It was known that Lincoln's religious views were "most nearly represented" by a man named Theodore Parker, who had a very close relationship with the terrorist John Brown, and had even funded his raid on Harpers Ferry. Parker was a radical Unitarian, a group who denied the divinity of Christ. Jesse Fell, another Unitarian, who was also the secretary of the Republican State Central Committee, wrote a biographical sketch of Lincoln for the 1860 election. Fell wrote about Lincoln, "I have no hesitation whatever in saying that, whilst he (Lincoln) held many opinions in common with the great mass of Christian believers, he did not believe in what are regarded as the orthodox or evangelical views of Christianity." Parker opened his house to Brown and treated him like royalty, after he murdered people in Kansas. Given that knowledge, it is more understandable that southerners were fearful of his election. With northern newspapers calling John Brown, the terrorist, a Saint less than a month after his attack on Harpers Ferry, southerners began viewing Brown, Parker, and Lincoln as conspirators against the south, regardless if one were in the 5% who owned slaves or the 95% who didn't. Newspapers in the north wrote like Wendell Phillips, "Virginia is a pirate ship and John Brown sails the seas as a Lord High Admiral of the Almighty, with his commission to sink every pirate he sees." Governor Joseph Brown of Georgia, before the end of the 7th of November, 1860, spoke in the capital of Milledgeville: We have within ourselves, all the elements of wealth, power, and national greatness, to an extent possessed probably by no other people on the face of the earth. With a vast and fertile territory, possessed of every natural advantage, bestowed by a kind Providence upon the most favored land, and with almost monopoly of the cotton culture of the world, if we were true to ourselves, our power would be invincible, and our prosperity unbounded.Horace Greeley, editor of the New York Tribune, wrote on November 10th: " And now, if the Cotton States consider the value of the Union debatable, we maintain their perfect right to discuss it. Nay, we hold with Jefferson to the inalienable right of communities to alter or abolish forms of government that have become oppressive or injurious; and if the Cotton States shall decide that they can do better out of the Union than in it, we insist on letting them go in peace. The right to secede may be a revolutionary one, but it exists nevertheless; and we do not see how one party can have a right to do what another party has a right to prevent. We must ever resist the asserted right of any State to remain in the Union and nullify or defy the laws thereof; to withdraw from the Union is quite another matter. And whenever a considerable section of our Union shall deliberately resolve to o out, we shall resist all coercive measures designed to keep it in. We hope never to live in a republic, whereof one section is pinned to the residue with bayonets." While he was a fervent abolitionist, he continued to say: " Any attempt to compel them [the seceded states] to remain, by force, would be contrary to the principles of the Declaration of Independence and to the ideas upon which human liberty is based...If the Declaration of Independence justified the secession from the British Empire of three million of subjects in 1776, it was not seen why it would not justify the secession of five millions of Southerners from the Union in 1861." The December 10th, 1861 issue of the Chicago newspaper Daily Chicago Times, confessed that the southerners were being exploited by the northern political policies regarding tariffs, which favored the northern capitalists: "The South has furnished near three-fourths of the entire exports of the country ... we have a tariff that protects our (Northern) manufacturers from thirty to fifty percent and enables us to consume large quantities of Southern cotton, and to compete in our whole home market with the skilled labor of Europe. This operates to compel the South to pay an indirect bounty to our skilled labor, of millions annually."

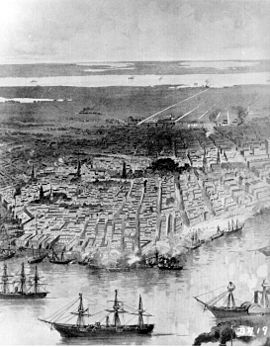

" Let the South adopt the free-trade system (Northern) commerce must be reduced to less than half what it is now." But it would be South Carolina which took the lead as it did in 1828. A convention was assembled, and on the 20th of December, the state voted to secede from the United States and resume its sovereign powers it believed it had delegated to the United States, not surrendered. Some states explicitly reserved their right to resume their delegated powers, namely New York, Rhode Island, and Virginia, statements which no other state objected to; New England had threatened multiple times to secede with no one claiming there was no right to secede at the time. South Carolina simply claimed it was acting in its sovereign and independent authority by removing its agent, the United States, from its foreign relations. The Indianapolis Daily Journal editorialized about South Carolina's secession: " Is any man so devoted to the idea of 'enforcing the law' and 'maintaining our glorious Constitution,' as not to see that maintaining it by civil war is the surest way to destroy it?" It continued, " the course to be pursued towards South Carolina...is to let her go freely and entirely." The Daily Capital City, a paper in Columbus, OH would publish February 9, 1861 an editorial titled "Men Change - Principles Never." It questioned the right of the federal government to coerce the seceded states back into the Union, " If the principle on which our Government is founded be not incorrect, it should be carried out at all hazards. There is and can be but one RIGHT in the premises - all else is wrong." One resident of Charleston, an Englishman by birth, wrote back to his family in England to explain the situation of how the northerners were exploiting the southern people: "Millions and millions have the South unjustly paid under the Northern protective tariff system. With secession, this tribute payment ceases. There is no wonder that the Northerners are union men and denounce the impropriety of secession. It occasions them pecuniary loss."Before its vote, on the 10th of December, a group of South Carolina congressmen asked President Buchanan for his pledge not to reinforce or change the military situation at Charleston Harbor, where troops were residing at Fort Moultrie (not Fort Sumter). The congressmen wanted to pay the government for federal property now within its borders, but the federal government would not treat with them on that matter. However, Buchanan offered his verbal assurances that he would not order the forts reinforced, and South Carolina would be informed if the President were to change that policy. After the vote, on the 26th, Major Anderson, who was in charge at Fort Moultrie, ordered his troops to move to Fort Sumter, a fort which could fire upon Charleston if it chose. Buchanan told the South Carolinians he couldn't order his return, since the takeover of Moultrie by the South Carolinians made that impossible. Nearly a fortnight later on the 5th of January, President Buchanan ordered the Star of the West to sail from New York with supplies to relieve the fort. South Carolinians fired across the ship, which turned back. Buchanan was resolved to hold the fort, though, and only send aid if requested, leaving things as they were for the time being. What Charleston residents knew, however, was that the city was allowing troops to purchase food and beverage in the city without restriction during this time. President Buchanan did make a final statement to Congress on the 4th of December, where he said: " The question, fairly stated, is: Has the Constitution delegated to Congress the power to coerce a State into submission which is attempting to withdraw or has actually withdrawn from the Confederacy? (a common term for the US at the time). If answered in the affirmative, it must be on the principle that the power has been conferred upon Congress to declare and make war against a State. After much serious reflection I have arrived at the conclusion that no such power has been delegated to Congress, nor to any other department of the Federal Government. It is manifest, upon an inspection of the Constitution, that this is not among the specific and enumerated powers granted to Congress; and it is equally apparent that its exercise is not 'necessary and proper for carrying into execution' any one of these powers. So far from this power having been delegated to Congress, it was expressly refused by the Convention which framed the Constitution." He concluded his statement: " The fact is, that our Union rests upon public opinion, and can never be cemented by the blood of its citizens shed in civil war. If it cannot live in the affections of the people, it must one day perish. Congress possesses many means of preserving it by conciliation; but the sword was not placed in their hand to preserve it by force." When President Lincoln made no public pronouncements on his willingness to defuse the situation, he made his way to Washington on a train ride, stopping at various points to give speeches, and finally approaching Washington in disguise, claiming an assassination plot against him. Soon after the incident with the Star of the West, six other states seceded: Mississippi, Florida, Alabama, Georgia, Louisiana, and Texas. From both North and South, representatives from several states met in Virginia to try to hold the Union together, but proposals for amending the Constitution, including the Corwin Amendment, which made slavery permanent, which Lincoln endorsed, would not be successful. The seven states met in Montgomery, Alabama, and formed a new government between them: the Confederate States of America. The first, provisional, Confederate Congress was held February 4, 1861, and adopted its provisional constitution. Four days later, it nominated Jefferson Davis, the Senator from Mississippi and former Secretary of War, as its provisional President. The Confederates sent peace envoys from January to April to Washington to meet with Abraham Lincoln to discuss items such as the assumption of debt, transfer of federal forts and armories to the confederate authorities, and trade, but each time they requested to meet, they were delayed for one reason or another, and Lincoln refused to see them or even acknowledge them. The envoys from the Confederate States did make clear that if the United States were to try to resupply forts, that would be considered an act of war. By about March, the federal Congress, now in control of the Republican party, which at this point was in favor of Henry Clay's American System, passed the Morrill Tariff, raising tariffs on hundreds of goods, and fueling secession sentiment across the South. At the same time, the South passed its own tariff of between 10 and 15%, which made the South essentially a free trade zone in comparison to the protectionist North. Despite the earlier support in the press for letting the South go, after the markets realized their profits would be jeopardized by the loss of southern markets, the tone changed: New York Times, March 30, 1861: " The predicament in which both the Government and the commerce of the country are placed, through the non-enforcement of our revenue laws, is now thoroughly understood the world over. ...If the manufacturer at Manchester can send his goods into the Western States through New-Orleans at a less cost than through New-York, he is a fool for not availing himself of his advantage. ...The English, almost to a man are Abolitionists of the ultra school. They abhor the principles of the Confederate States, but they intend to trade with them notwithstanding. We do not propose to offer a remonstrance, unless we are prepared by force to make good our position.

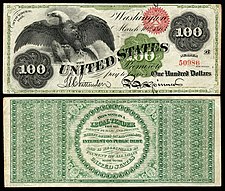

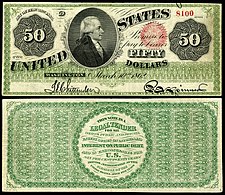

...If the importations of the country are made through Southern ports, its exports will go through the same channel. This is inevitable. The produce of the West, instead of coming to our own port by millions of tons, to be transported abroad by the same ships through which we received our importations, will seek other routes and other outlets. With the loss of our foreign trade, what is to become of our public works, conducted at the cost of many hundred millions of dollars, to turn into our harbor the products of the interior? They share in the common ruin. So do our manufacturers. ...Once at New-Orleans, goods may be distributed over the whole country, duty free. The process is perfectly simple. No remedy is suggested, except force or treaty. We see no other. ...The commercial bearing of the question has acted upon the North...We now see clearly whither we are tending, and the policy we must adopt. With us it is no longer an abstract question -- one of constitutional construction, or of the reserved or delegated powers of the State or Federal Government, but of material existence and moral position both at home and abroad. England and France were indifferent spectators till their interests were affected. We were divided and confused till our pockets were touched. " Boston Transcript : It does not require extraordinary sagacity to perceive that trade is perhaps the controlling motive operating to prevent the return of the seceding States to the Union. Slavery is an issue, yes, but the mask has been thrown off, and it is apparent that the people of the principle seceding States are now for commercial independence. The Union Democrat, from Manchester, NH: " The Southern Confederacy will not employ our ships or buy our goods. What is our shipping without it? Literally nothing. The transportation of cotton and its fabrics employs more ships than all other trade. It is very clear that the South gains by this process, and we lose. No - we MUST NOT "let the South go."" The New York Evening Post (March 12, 1861): " That either revenue from duties must be collected in the ports of the rebel states, or the ports must be closed to importations from abroad,...If neither of these things be done, our revenue laws are substantially repealed; the sources which supply our treasury will be dried up; we shall have no money to carry on the government; the nation will become bankrupt before the next crop of corn is ripe. There will be nothing to furnish means of subsistence to the army; nothing to keep our navy afloat; nothing to pay the salaries of the public officers; the present order of things must come to a dead stop...Allow railroad iron to be entered at Savannah with the low duty of ten per cent, which is all that the Southern Confederacy think of laying on imported goods, and not an ounce more would be imported at New York; the railways would be supplied from the southern ports. What, then, is left for our government?" Behind the backs of the rest of his cabinet, Lincoln ordered two secret missions to resupply both Fort Sumter near Charleston, and Fort Pickens near Pensacola, breaking the de facto truce with the Confederates, with the support of Montgomery Blair, his postmaster general, Gustavus Fox, Assistant Secretary of the Navy, and Gideon Welles, his Navy Secretary. He either intentionally or not, ordered the flotilla going to Charleston to take its orders from a ship that he then sent to Pensacola, rendering any military option there impotent. His decision, as his biographers John Nicolay and John Hay would later write, was decided by November. Lincoln wrote to Elihu Washburne: " Please present my respects to the General (Winfield Scott) , and tell him confidentially, I shall be obliged to him to be as well prepared as he can to either hold, or retake, the forts, as the case may require, at, and after the inauguration." Fox took Welles's idea, namely that it was " very important that the Rebels strike the first blow in the conflict," and then worked out the details of a plan. He wrote to Montgomery Blair, the future Postmaster General, in February, that " I simply propose three tugs, convoyed by light-draft men-of-war." and " The first tug to lead in empty, to open their fire." Lincoln had two difficult choices: reinforce the fort and risk losing the Upper South, or not do anything and risk looking weak like Buchanan, and legitimizing the Confederacy. Lincoln made his choice. The South had two difficult choices: do nothing and look weak, being humiliated internationally if they allowed Lincoln to resupply the forts, or fire upon a coming flotilla and risk being seen as the aggressors. In what may be an apocryphal quote, when asked "Why not let the South go?" President Lincoln appeared to reply, "Let the South go! Where then shall we get our revenue?" In Lincoln's own words of 1864, "and so the war came." First Flag of the Confederate States The new Confederacy, with seven states, sought to create a flag similar to that of the United States. They felt their new Confederation was simply a restoration of the original intent of the Union, and the first flag was created, called the "Stars and Bars." It had a red, white, and red stripe, and a blue canton with seven stars for the seven states.

|

|

jjohnson

Chief petty officer

Posts: 144

Likes: 219

|

Post by jjohnson on Nov 8, 2019 17:09:33 GMT

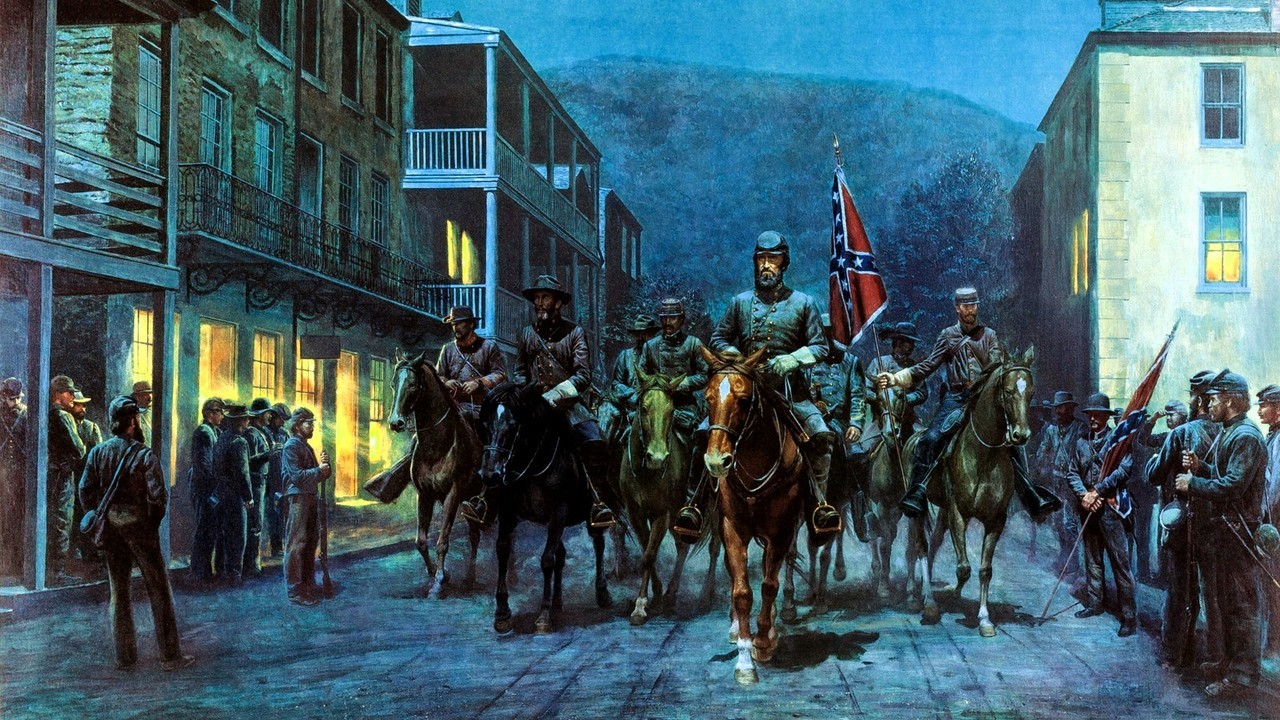

Chapter 2: Fire Free

Georgia Secedes

On the 7th of January, Senator Robert Toombs delivered a speech to the Senate, his last before departing, concerning equal right to settle territories as a right violated by the New Englanders. On the 19th of January, Georgia seceded from the Union. An excerpt from his speech: " The law of nature, the law of justice, would say—and it is so expounded by the publicists—that equal rights in the common property shall be enjoyed. Even in a monarchy the king can not prevent the subjects from enjoying equality in the disposition of the public property. Even in a despotic government this principle is recognized. It was the blood and the money of the whole people (says the learned Grotius, and say all the publicists) which acquired the public property, and therefore it is not the property of the sovereign. This right of equality being, then, according to justice and natural equity, a right belonging to all States, when did we give it up? You say Congress has a right to pass rules and regulations concerning the Territory and other property of the United States. Very well. Does that exclude those whose blood and money paid for it? Does “dispose of” mean to rob the rightful owners? You must show a better title than that, or a better sword than we have.

What, then, will you take? You will take nothing but your own judgment; that is, you will not only judge for yourselves, not only discard the court, discard our construction, discard the practise of the government, but you will drive us out, simply because you will it. Come and do it! You have sapped the foundations of society; you have destroyed almost all hope of peace. In a compact where there is no common arbiter, where the parties finally decide for themselves, the sword alone at last becomes the real, if not the constitutional, arbiter. Your party says that you will not take the decision of the Supreme Court. You said so at Chicago; you said so in committee; every man of you in both Houses says so. What are you going to do? You say we shall submit to your construction. We shall do it, if you can make us; but not otherwise, or in any other manner. That is settled. You may call it secession, or you may call it revolution; but there is a big fact standing before you, ready to oppose you—that fact is, freemen with arms in their hands."

Mississippi Secedes

In a convention of her people, Mississippi votes to secede from the Union on the 9th of January. Her senator, Jefferson Davis, gives a farewell address to the US Senate on the 21st and leaves for his home country. An excerpt from his speech: " I find in myself, perhaps, a type of the general feeling of my constituents towards yours. I am sure I feel no hostility to you, Senators from the North. I am sure there is not one of you, whatever sharp discussion there may have been between us, to whom I cannot now say, in the presence of my God, I wish you well; and such, I am sure, is the feeling of the people whom I represent towards those whom you represent. I therefore feel that I but express their desire when I say I hope, and they hope, for peaceful relations with you, though we must part. They may be mutually beneficial to us in the future, as they have been in the past, if you so will it. The reverse may bring disaster on every portion of the country; and if you will have it thus, we will invoke the God of our fathers, who delivered them from the power of the lion, to protect us from the ravages of the bear; and thus, putting our trust in God and in our own firm hearts and strong arms, we will vindicate the right as best we may."

Confederate States of AmericaTexas, Florida, Alabama, Louisiana all secede in January or February, and meet to form the Confederate States of America in Montgomery. Their constitution is nearly identical to that of the United States, adding a few new powers such as a line-item veto, forbiddance of federal funding for internal improvements, and allowing cabinet members a seat in the House, but also explicitly mentioning what was tacitly mentioned in the US Constitution - slavery. Uniquely, the Confederate Constitution expressly forbade the slave trade, while the US Constitution allowed it until 1808.

Lincoln's Inauguration

In his inaugural address, Lincoln stated his main purpose is, “ to collect the duties and imposts, but beyond what may be necessary for these objects, there will be no invasion – no using of force against or among the people anywhere.”

Ominously, he said: " In your hands, my dissatisfied fellow-countrymen, and not in mine, is the momentous issue of civil war. The Government will not assail you. You can have no conflict without being yourselves the aggressors." Unique to his inaugural address, Lincoln claimed the Union was older than the States, despite the fact that the Union began in 1776, or 1775 depending on the point of view, and states had existed since 1607 in the case of Virginia. At that time there was no 'union' other than the one between the Virginia colony and Great Britain, from which Virginia seceded independently of the other states. Lincoln also claimed the Constitution was older than the states, despite its having been written in 1787, 180 years after the founding of Virginia. He also stated that he did not believe the Constitution to be a compact, despite many across the Union holding that very opinion; he claimed all had to agree it was broken, despite the law of contracts being that the parties to the contract, in this case, the several States, were the common judge of when the contract is violated. Lincoln also claimed the Union itself was a government, while many in the southern states believed it was simply a common agent for international issues like trade and war. The Foreign View

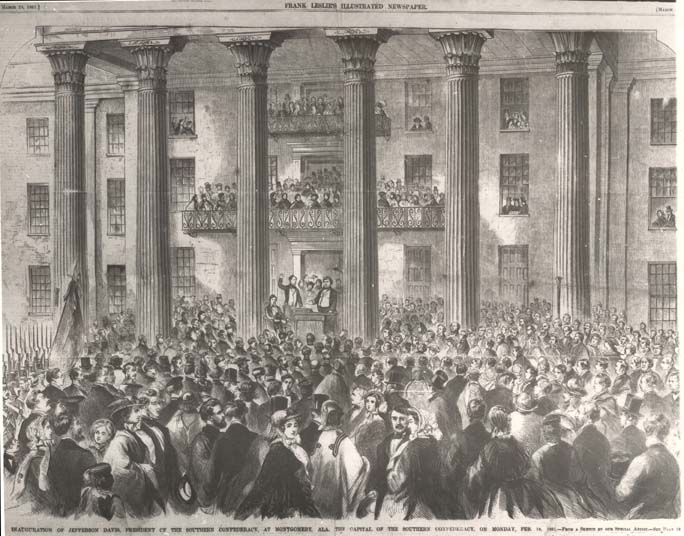

Anthony Trollope, a British citizen who had traveled extensively through the North and South before and around the time of secession wrote to his fellow British subjects in 1861 about the developing situation in North America: "The South is seceding from the North because the two are not homogeneous. They have different instincts, different appetites, different morals, and a different culture." He continued: "They (the Southerners) had become a separate people, dissevered from the North by habits, morals, institutions, pursuits, and every conceivable difference in their modes of thought and action. They still spoke the same language, as do Austria and Prussia; but beyond that tie of language they had no bond but that of a meager political union..." Davis's Inauguration At Montgomery, Alabama, President Jefferson Davis gave his inaugural address, in which he declared that government rests on consent of the governed, not on coercion, and on the preservation of the rights of the states and citizens. Notably, he said: " Sustained by the consciousness that the transition from the former Union to the present Confederacy has not proceeded from a disregard on our part of just obligations, or any failure to perform every constitutional duty, moved by no interest or passion to invade the rights of others, anxious to cultivate peace and commerce with all nations, if we may not hope to avoid war, we may at least expect that posterity will acquit us of having needlessly engaged in it." Davis's wife Varina was less enthused about his being chosen as President. Cotton RunPresident Davis awoke in a sweat, having had a horrible dream of a snake encircling the Confederacy, choking it off slowly until he felt himself starving. The snake hissed in his dream, "If you had sold your cotton you might have been able to have arms against me." He couldn't sleep the rest of the night, so he wrote out a few orders, and began what would be called the "Cotton Run." The Confederate government quickly moved to purchase all cotton not currently sold, and rushed the cotton overseas to Europe for gold, guns, munitions, medicines, boots, saddles, and other military necessities. On the way back, a number of Europeans, including a number of Prussian military officers, Bavarians, and Rhinelanders, a number of Dutch, Italians, Poles, even some French, Irish, Scots, Welsh, and Englishmen traveled of their own volition to the South to join the fight, but nowhere near the numbers of Europeans who would come to fight for the North. In total, before the blockade could get going by mid to late 1862, the Confederates were able to export their 1861 cotton crop to gain over $150 million in specie, which meant that they were able to fund their government, lower interest and speculation, and improve their morale and overseas respect, which would do much to encourage the chances of foreign recognition later. Even after the expenses of government were taken care of, there were over $35 million in specie to help keep interest low. Millions of dollars were raised by the Cotton Run before the North could put a blockade on the South, money that went towards valuable munitions and supplies that did much to help reduce southern casualties in the war. Virginia Votes Against SecessionOn the 13th of February, Virginia convened a secession convention, but voted down secession multiple times during the convention's existence. The state had produced several presidents, and several statesmen important to the formation of the Union and would not easily leave. The convention members were waiting for Lincoln to resolve the issue peacefully, and would wait for the President. Secretly, however, Lincoln plotted against even this convention. Lincoln and Seward found a Constitutional Union man they hoped would help adjourn the convention to prevent Virginia from seceding by the name of Allan Magruder. Magruder was asked to go to Richmond, where the convention had convened, to see Judge George Summers to try to get him to come to Washington to speak to Lincoln. He couldn't leave, so they found another union man, John Baldwin, who would go to talk with Lincoln. John Baldwin met with Lincoln on April 4th, and urged him to call a conference of the states for the purpose of issuing a proclamation of peace and union, which would give an official assurance of Lincoln's "yearnings for peace." According to Senate testimony, Baldwin quoted Lincoln as saying " I fear you are too late." At this time, Baldwin did not know it, but Lincoln had more than one secret war expedition on the move. Lincoln replied with an urging plea about the convention, saying, " Why don't you adjourn the convention? Yes, I mean sine die. It is a standing menace to me." Baldwin, according to his testimony, refused to seek the adjournment of the convention, and warned the President, " If a gun is fired, Virginia will secede within 48 hours." President Lincoln gave him no assurances, and as he left, he spoke with seven other states' governors waiting in the Executive Mansion. Baldwin didn't know what they would say to the President regarding force or not. The Plot for Fort Pickens

Before the more famous fort in South Carolina was fired upon, in January of the same year, Captain Vogdes was sent with an armed forces on the USS Brooklyn to reinforce Fort Pickens in Florida, but he was stopped by the so-called 'armistice' of the 29th of January. So his force stayed there on the Brooklyn. When Lincoln became President, he was made aware of these facts, and sent the following order March 12th, 1861: Sir: (C) At the first favorable opportunity, you will land your company, reinforce Fort Pickens, and hold the same till further orders, etc.

By command of Lieut. Gen. ScottCaptain Vogdes received this order on the 31st of March, but instead of obeying the order immediately, sent the following reply, avoiding war on the 1st of April: Sir: (D) Herewith I send you a copy of an order received by me last night. You will see by it that I am directed to land my command at the earliest opportunity. I have therefore to request that you will place at my disposal such boats and other means as will enable me to carry into effect the enclosed order.

(Signed) I. VOGDES, Capt. 1st Artly. Comdg. Captain Adams reported back after this to the Secretary of the Navy, Gideon Welles: (E) " It would be considered not only a declaration but an act of war; and would be resisted to the utmost.

"Both sides are faithfully observing the agreement (armistice) entered into by the United States Government and Mr.

Mallory and Colonel Chase, which binds us not to reinforce Fort Pickens unless it shall be attacked or threatened. It binds them

not to attack it unless we should attempt to reinforce it." Secretary Wells sent a confidential reply on the 6th of April: " Navy Dept., April 6th, 1861. "(Confidential).

Sir: (F) Your dispatch of April 1st is received. The Department regrets that you did not comply with the request of Capt. Vogdes. You will immediately on the first favorable opportunity after receipt of this order, afford every facility to Capt. Vogdes to enable him to land the troops under his command, it being the wish and intention of the Navy Department to co-operate with the War Department, in that object. (Signed) GIDEON WELLES, Secty. of the Navy" Lt Worden traveled from Florida up through the Confederacy and back to DC. He memorized and destroyed the orders, and when confronted by General Bragg, he told him he had a verbal message of a peaceful nature for Captain Adams, which was not entirely accurate. Four years later, Adams and Worden reported this information to Congress, and in 1867, would form evidence used by the Democrats in Lincoln's impeachment that he effectively started the war on March 12th, as the act of military force was an act of war, placing the force and power of the government behind it. NOTE: the commands above are in the historic records in the War of the Rebellion and in a booklet called "Truth of the War Conspiracy of 1861" from which I excerpted them. They are not my own words but those of the people at the time. The Plot for Fort SumterMuch of the information for this would come from Senate investigations that began directly after the war. It was found that Gustavus Fox had written a letter to Montgomery Blair on March 1st, explicitly stating that the object of his plans was "the reinforcing of Fort Sumter." When testifying before the Senate in August of 1865, he confessed that on the 6th of February, he had met Lt. Normal Hall at Army Headquarters. Hall was sent by Major Anderson from Fort Sumter, and had several conferences with Fox about relieving the fort. Thus, a plot between Fox, Hall, Blair, Lincoln, and Welles to 'reinforce' the fort, thus sparking the war. On the 20th of December, South Carolina had seceded, but had not seized any forts, as that would have been in violation of the existing truce between the US and South Carolina not to change the military situation. On the 26th, Major Anderson spiked the guns and burned the carriages at Fort Moultrie and left for Sumter, after which South Carolina seized the other forts. On the 29th of March, after the Senate had adjourned, Abraham Lincoln sent the following telegram to the Secretary of the Navy:

Executive Mansion, March 29th, 1861.

"Sir: I desire that an expedition, to move by sea be got ready to sail as early as the 6th of April next, the whole according to memorandum attached: and that you co-operate with the Secretary of War for that object. Your obedient servant, (Signed) A. LINCOLN.

Lincoln directed the secretary of the navy to prepare three ships of war, the Pocahontas, Pawnee, and Harriet Lane, with 300 seamen and a month's stores, and for the war department to ready 200 men with one year's stores. Gustavus Fox was sent to New York on March 30th to prepare everything for Sumter. Down in South Carolina, Governor Pickens of South Carolina began asking about the fort being evauated, and sent a telegram to the Confederate Peace Commissioners, who were communicating through an intermediary, Judge Campbell (as Lincoln refused to meet with the Confederates, which would legitimize them). Secretary Seward assured Judge Campbell, who then told the commissioners, that he would receive an answer by April 1st to the governor's telegram. Seward replied to Judge Campbell, " The President may desire to supply Fort Sumter but will not do so." He then added to this, " There is no design to reinforce Fort Sumter." On that same day, General Winfield Scott sent a telegram to begin the preparations for sending warships to Fort Pickens and Fort Sumter. Colonel Harvey Brown received the following telegram.

Hd. Qurs. of the Army, Washington, April 1st, 1861.

Sir: You have been designated to take command of an expedition to reinforce and hold Fort Pickens in the harbor of Pensacola. You will proceed to New York where steam transportation for four companies will be engaged ;—and putting on board such supplies as you can ship without delay proceed at once to your destination. The object and destination of this expedition will he communicated to no one to whom it is not already known. (Signed) WINFIELD SCOTT.

President Lincoln sent the following telegram to Scott in order to make sure his order was clear.

Executive Mansion, Washington, April 1st, 1861.

All officers of the Army and Navy, to whom this order may be exhibited will aid by every means in their power the expedition under the command of Colonel Brown; supply him with men and material; and co-operating with him as he may desire. (Signed) ABRAHAM LINCOLN. Gustavus Fox bore the following telegram to Lt. Col. Scott from General Scott, ordering him to embark with a detachment to Sumter: Hd. Qurs. of the Army, (Confidential) Washington, April 4th, 1861. "Sir: This will be handed to you by Captain G. V. Fox, an ex-officer of the Navy. He is charged by authority here, with the command of an expedition (under cover of certain ships of war) whose object is, to reinforce Fort Sumter. To embark with Captain Fox, you will cause a detachment of recruits, say about 200, to be immediately organized at Fort Columbus, with competent number of officers, arms, ammunition, and subsistence, with other necessaries needed for the augmented garrison at Fort Sumter. Consult Captain Fox, etc.

(Signed) WINFIELD SCOTT. To Lieut. Col. H. L. Scott, Aide de Camp."

From President Lincoln, the following telegram was sent to Lt. Porter on April 1st, ordering him to Pensacola to take Fort Pickens.

"Executive Mansion, Washington, April 1st, 1861.

"Sir: (2) You will proceed to New York and with least possible delay assume command of any steamer available. Proceed to Pensacola Harbor, and, at any cost or risk, prevent any expedition from the main land reaching Fort Pickens, or Santa Rosa. You will exhibit this order to any Naval Officer at Pensacola, if you deem it necessary, after you have established yourself within the harbor. This order, its object, and your destination will be communicated to no person whatever, until you reach the harbor of Pensacola.

(Signed) ABRAHAM LINCOLN. To Lieutenant D. D. Porter, U. S. Navy. Curiously, President Lincoln sent the following telegram to the man in charge of the Navy Yard, ordering him not to inform the Secretary of the Navy of his mission: Executive Mansion, April 1st, 1861. Sir: You will fit out the Powhatan without delay. Lieutenant Porter will relieve Captain Mercer in command of her. She is bound on secret service; and you will under no circumstances communicate to the Navy Department the fact that she is fitting out.

(Signed) ABRAHAM LINCOLN. To Commandant Navy Yard, New York