Post by lordroel on Aug 11, 2016 15:14:17 GMT

How NATO and the Warsaw Pact planed to win World War III

How the Warsaw Pact Planned to Win World War Three in Europe

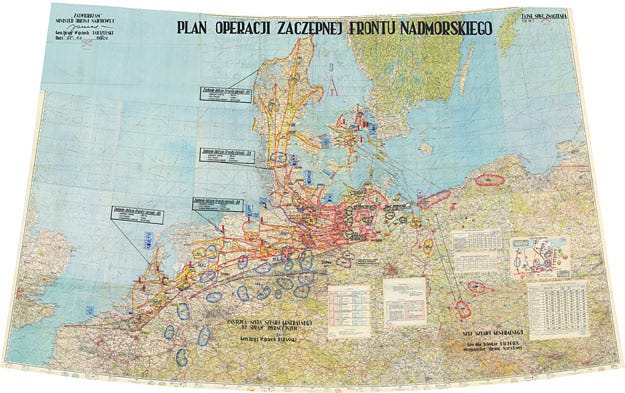

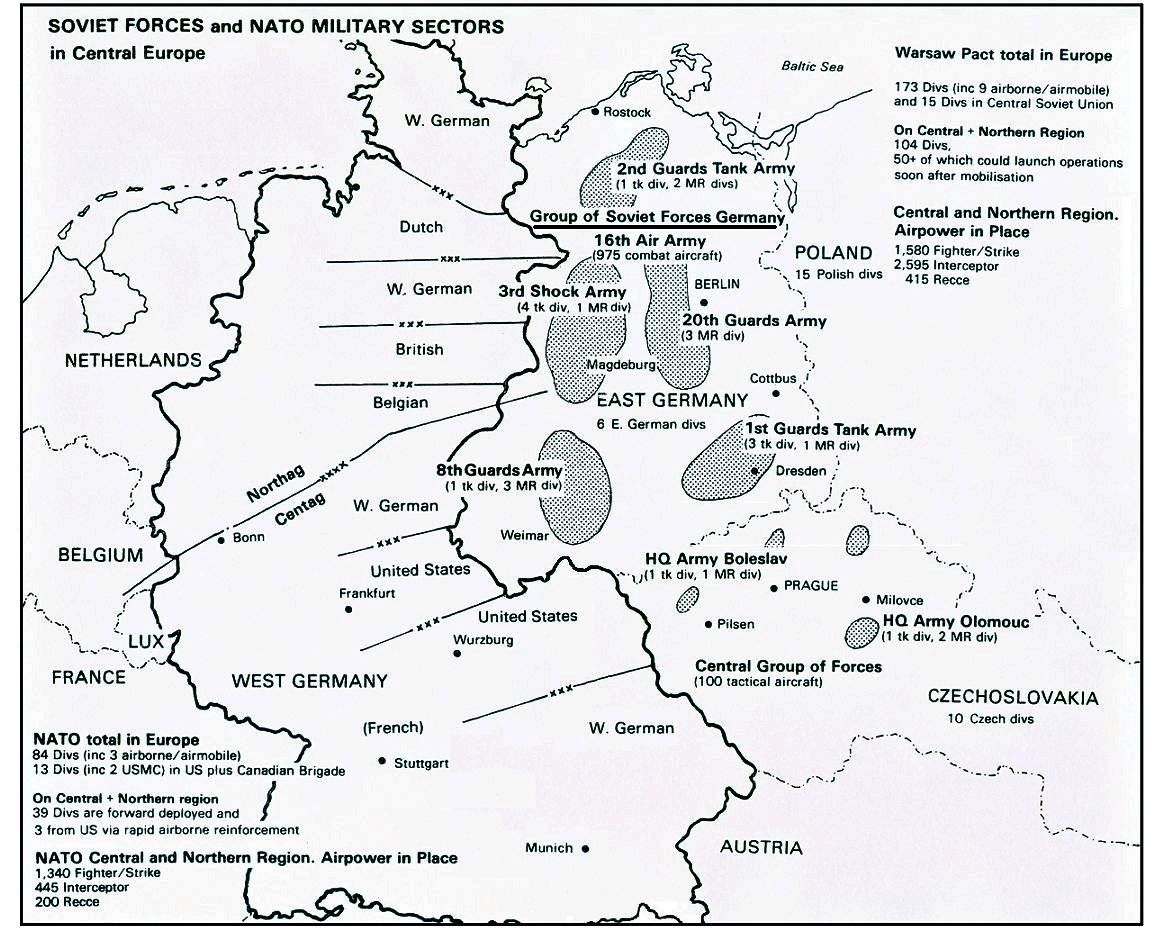

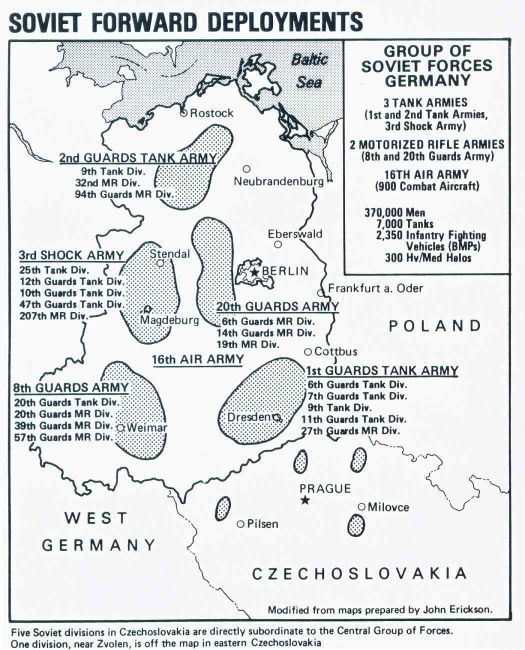

Map of Soviet forces in Germany

The scenario is set in the late 1980s, assumed that the forces of the Soviet Union and the rest of the Warsaw Pact—namely East Germany, Poland, Czechoslovakia and Hungary—steamrollered West Germany to defeat NATO. The plan assumed the western alliance would defend as far forward as possible while avoiding the use of tactical nuclear weapons.

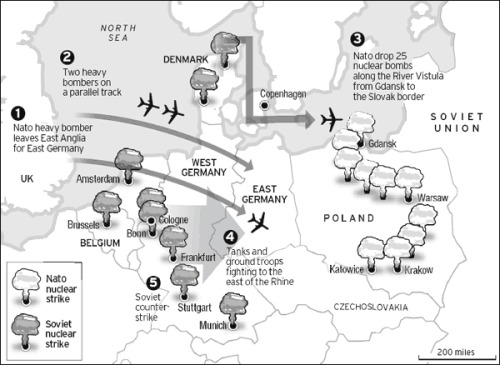

But what about the Warsaw Pact? After the Cold War ended, the Polish government made public classified Soviet documents that revealed the likely war plan. The plan, known as “Seven Days to the Rhine,” was the basis of 1979 military exercise that assumed NATO as the aggressor, having nuked a series of twenty-five targets in Poland, including Warsaw and the port of Gdansk. The cover story of countering aggression was a mere fig leaf for the true nature of the anticipated conflict: a bolt-from-the-blue Soviet attack against NATO.

By the 1980s NATO had shifted to a “Flexible Response” nuclear doctrine: the alliance was prepared to use nuclear weapons, but would seek to win the war conventionally. This is in stark contrast to the Warsaw Pact, which saw their use as inevitable and planned to use them from the outset. Such early would confer the pact an enormous strategic advantage over NATO.

In “Seven Days to the Rhine,” Soviet nuclear forces would destroy Hamburg, Dusseldorf, Cologne, Frankfurt, Stuttgart, Munich and the West German capital of Bonn. NATO headquarters in Brussels would be annihilated, as would the Belgian port of Antwerp. The Dutch capital and port of Amsterdam would also be destroyed. Denmark would suffer two nuclear strikes.

1976 map of probable axes of attack for the Warsaw Pact forces into Europe.

The result would be a headless NATO and the destruction or demoralization of civilian governments in West Germany, Belgium, the Netherlands and Denmark—precisely the countries likely to be occupied at the end of the seven days. The elimination of the port cities of Hamburg, Antwerp and Amsterdam would severely curtail NATO’s ability to flow reinforcements from the United Kingdom and North America.

Curiously, France and the United Kingdom were to be spared nuclear strikes. This is probably because both had independent nuclear arsenals not tied to the United States. The United States might have hesitated to retaliate for fear of escalating to strategic nuclear warfare, but for France and the UK the European atomic battlefield was much closer and the dividing line between tactical and strategic not so clear-cut. The Soviet leadership probably had no intention of continuing war with either one on the eighth day.

After the Warsaw Pact had launched nuclear strikes, conventional forces would be sent in to conquer. Seven Days to the Rhine assumed a radioactive zone that used to be called Poland, dividing the Soviet Union from its forces in East Germany, Czechoslovakia and Hungary. Those forces, along with their East German, Czechoslovak and Hungarian counterparts, would need to suffice to carry out the attack. While Polish forces were theoretically available, by 1979 the Soviets would have reason to suspect their political reliability.

As a result, total forces committed would be roughly the same number of forces the pact would have in a no-notice attack on NATO. Planning with the assumption of a radioactive curtain severing forward pact forces from the Soviet Union itself is also a reasonable model for assuming a quick war without a prewar buildup of ammunition and fuel from the Soviet Union.

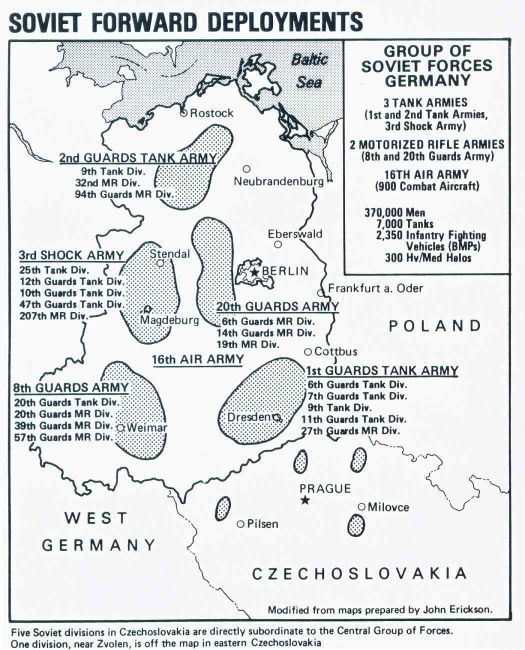

Leading the spearhead aimed at the heart of NATO would be the Group of Soviet Forces in Germany. The GSFG was comprised of five armies, each with three or four tank and motor-rifle (mechanized infantry) divisions.

In the North, the Soviet and East German attack force would consist of the Soviet Second Guards Tank Army, Twentieth Guards Army and Third Shock Army, consisting of seven tank divisions and five motor rifle divisions. East Germany’s National People’s Army, considered the best of the non-Soviet pact forces, would contribute two tank and four mechanized-infantry divisions.

This combined northern force of eighteen combat divisions, plus artillery, air assault and special forces, would smash into the combined Danish, Dutch, West German, British and Belgian forces facing them. The battle would take place on the so-called North German Plain, a stretch of relatively flat, rolling country from the inner German border to the Low Countries. This was considered the quickest, most direct way to knock out the largest number of NATO countries.

Somewhere in the endless stream of combat vehicles headed west would be what was known as the Operational Maneuver Group, or OMG. Anywhere from two brigades to two divisions large, the OMG would be held in reserve until a breakthrough was achieved. Once committed, the OMG would lunge deep behind enemy lines, cutting off NATO forces as it did so.

In southern Germany, the spearhead would be the Soviet Eighth Guards Army and the First Guards Tank Army, totaling three tank divisions and three motor rifle divisions. The Soviet Central Group of Forces, based in Czechoslovakia, would add two tank and three motor rifle divisions; the Czechoslovak People’s Army would also add three tank and five motor rifle divisions. Czechoslovak forces were formidable in theory, but the Soviets likely still considered them politically suspect twenty years after the Prague Spring of 1968.

This southern force of nineteen divisions would enjoy the shortest route to the Rhine River, only 120 miles as the crow flies, but faced serious military and geographical obstacles. The ten West German and American divisions facing them were among the best-equipped in NATO, and the correlation of forces, to use a Soviet Army phrase, did not favor the attacker. The terrain was a mixture of hills, mountains and connecting valleys, all of which strongly favored the defender.

In the meantime, Soviet airborne and air assault forces would fan out and occupy key bridges, particularly over the Weser and Rhine Rivers. Seizing river crossings would be essential for maintaining the momentum of the ground offensive. Airfields, military headquarters and known alternate seats of government would also be targets. Soviet spetsnaz special forces would also target NATO tactical nuclear weapons, seeking to neutralize Pershing II, Ground Launched Cruise Missiles and nuclear gravity bombs before they could be used.

At sea, the Soviet Navy would immediately go on the offensive. The Soviet Navy would, like the German Navy before it, try to sever the naval supply line from North America to Europe. The Soviet Navy would also immediately try to destroy American aircraft carriers, which with their airborne nuclear weapons were a wild card, capable of delivering nuclear strikes against a variety of targets over vast ranges.

The most important goal of the Soviet Navy would be to safeguard its ballistic missile submarines hiding in the Barents Sea bastion. Whether or not Moscow won or lost in the conventional realm, this would preserve a second-strike strategic capability against the United States. If the Americans were successful in wiping out Soviet boomers, that could embolden them to launch a nuclear first strike.

Warsaw Pact aviation was to be very busy. Assuming a short seven-day war, there would not be time to execute a proper air-defense suppression campaign. Much of NATO’s leadership would have been killed during the nuclear attacks, and as a result NATO air defenses would be disorganized. Pact air forces might simply press on without attempting to destroy NATO air defenses.

Assuming a no-notice war, most combat missions would be preplanned counter-air missions and air strikes against known airfields, army bases and NATO ground positions. Prepositioned stocks of U.S. Army equipment in Germany and the Netherlands would be particularly vulnerable, allowing the pact to knock out entire divisions without fighting them.

The Warsaw Pact plan makes clear two things. First, in a surprise attack, the most important forces are the ground forces. The quicker they can advance, the sooner they can overrun NATO—and that includes air bases and naval facilities. The faster they can force West Germany to surrender, the sooner the rest of NATO runs out of reasons to continue fighting—and the specter of all-out nuclear war recedes.

Second, NATO would have lost the war. NATO’s assumption that the war would gradually escalate to nuclear weapons would have been fatal against an adversary that planned to use them on Day One. The use of nukes in Western Europe would devolved the decision to employ them away from NATO as a collective body to heads of the United States, France and the UK. All three would be forced to use battlefield nukes to save their troops—and risk escalation that would devastate their homelands—or walk away from the rest of NATO.

While the World War III scenario in Europe was always unlikely, it was also the most dangerous. We now know that, instead of an escalation to nuclear war being a possibility, it was virtually guaranteed. The only question would have been to what extent—and whether or not human civilization would have survived it.

How NATO Planned to Win World War Three in Europe

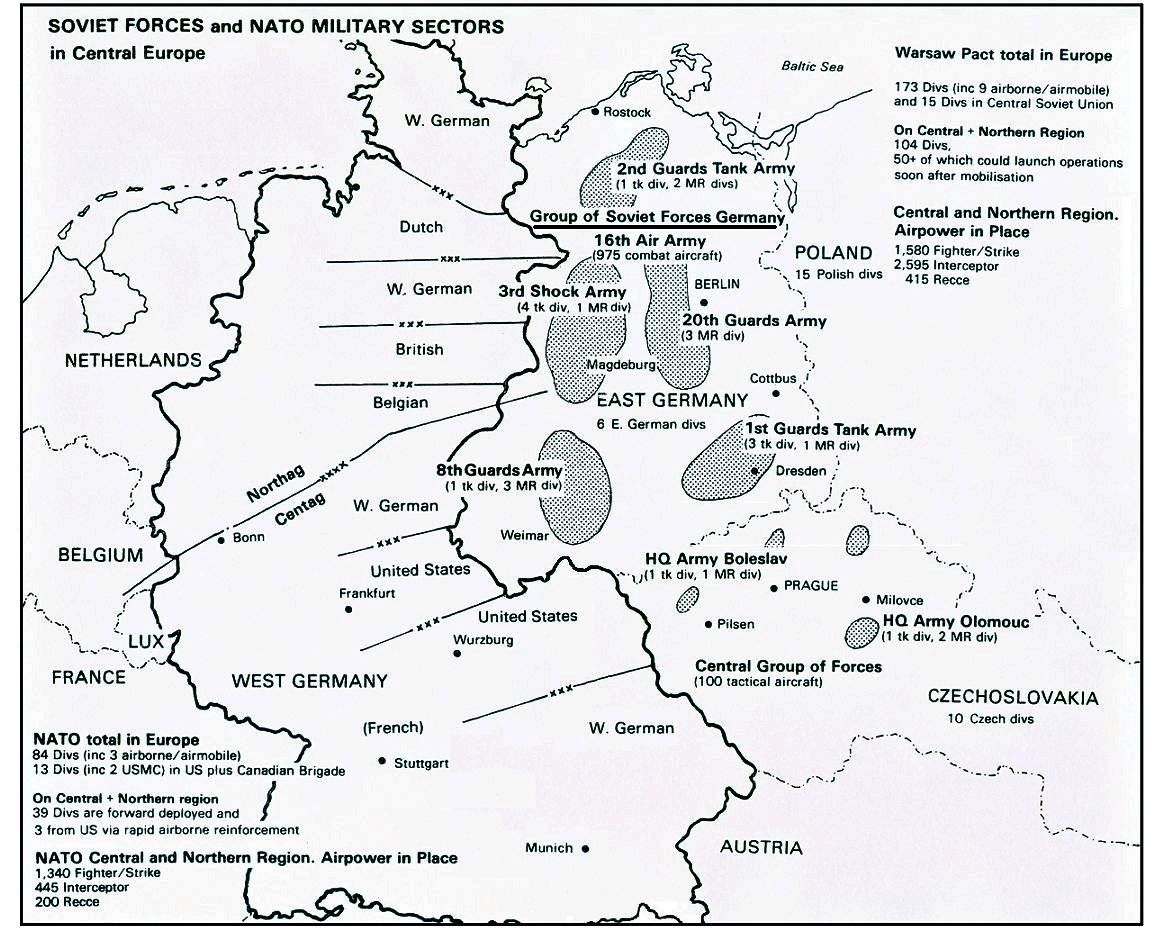

Map of NATO and Warsaw Pact forces in Europe

The North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO) was formed in 1949 to oppose Soviet expansionism in Western Europe. The end of the war saw the Soviet Union solidify its gains in Eastern Europe, garrisoning countries such as Poland, Hungary, Czechoslovakia, Romania, Bulgaria and East Germany. NATO was a direct response to the raising of what Winston Churchill deemed the “Iron Curtain.”

At the time, American and Western European planners felt that if war were to break out between West and Stalin’s Russia, it would quite logically take place in Europe. The reality of nuclear weapons, however, meant that the two sides avoided direct confrontation and instead fought a series of proxy wars worldwide. That having been said, for the Soviet Union an invasion of Western Europe carried the biggest risk—and the biggest reward.

NATO’s strategic mission was to prevent the destruction of the alliance by military force. Essential to that were four wartime goals: gaining air superiority, keeping sea lines of communication open to North America, maintaining the territorial integrity of West Germany and avoiding the use of nuclear weapons. Were NATO to lose any of these four, the war was as good as over.

In 1988, NATO’s plan for the defense of Western Europe was the doctrine of forward defense, in which Soviet and Warsaw Pact forces were stopped as far close to the inner German border as possible. A defense in depth—which experience on the Eastern Front in World War II had proved superior—would have imperiled virtually the entire West German population and forty years of postwar rebuilding.

NATO seemingly had no unified battle plan other than to “man the line” until Soviet and Warsaw Pact forces were exhausted—whereupon counterattacks could be executed to restore prewar borders. West German Army forces, inflexible at the strategic level, were allowed a level of flexibility at the tactical level. The United States devised AirLand Battle, a doctrine that stipulated ground and air units would work together to strike the enemy simultaneously, from the forward edge of the battle area to deep behind enemy lines.

At sea, the primary mission of NATO’s naval forces was to keep the sea lanes between North America and Europe open, in order to guarantee the flow of reinforcements from the United States and Canada. NATO patrol aircraft, ships and submarines would seek out Soviet submarines attempting to interdict supply convoys, trying to keep them north of an imaginary line connecting Greenland, Iceland and the United Kingdom.

In the Norwegian Sea, the U.S. Navy planned to surge two to three carrier battle groups, plus a battleship surface action group to attack Soviet air and naval bases of the Northern Fleet. This direct attack on the Soviet homeland was meant to divert enemy attention from the convoys, destroy air and naval facilities, and starve enemy units at sea of support. It would also, unofficially, isolate Soviet ballistic missile submarines from their land-based support, leaving them in a position to be hunted down.

NATO naval forces would bottle up Soviet, Polish and East German naval forces inside the Baltic Sea, and prevent a seaborne invasion of Denmark. West German naval forces would be on alert for Polish marine units attempting to execute a landing north of Hamburg.

In the air, NATO’s air fleets would be assigned to several roles. American F-15s and F-16s, British Tornado ADV, and German F-4 Phantom jets, among many others, would attempt to establish air superiority over the continent. Meanwhile, British and German Tornado IDS low-level strike bombers would fly counter-air missions, bombing Warsaw Pact airfields in East Germany and Poland. USAF F-111 fighter bombers and other alliance strike jets would perform interdiction missions, bombing bridges, headquarters, supply and other targets to slow the Warsaw Pact advance. Finally, American A-10 Warthogs, German Alpha Jets and Royal Air Force Harriers would be providing forward air support to beleaguered NATO ground troops.

Yet it was on the ground was where the war would have been decided. Everything supported the war on the ground—even the air war, for the ideal Soviet solution to NATO air superiority was to put a tank on every enemy airfield.

Technologically, NATO ground forces had an edge, and the decade was a period where many combat systems were introduced that are still in service today. In 1988, the Europe-based U.S. Seventh Army was several years into fielding its “Big Five” combat systems: the M1 Abrams tank, M2 Bradley infantry fighting vehicle, AH-64 Apache attack helicopter, UH-60 Blackhawk transport and Patriot air defense missile, which would greatly upgrade the Army’s ability to fight AirLand Battle. West Germany had begun deploying its second generation tank, the Leopard II, also being deployed by the Netherlands, and had the Marder infantry combat vehicle. At the same time, the introduction of the Challenger tank and Warrior infantry fighting vehicle reinvigorated the British Army of the Rhine’s combat formations.

NORTHAG, or Northern Army Group, was assigned to the north half of West Germany. NORTHAG was committed to defending the North German Plain, a stretch of relatively flat, rolling country from the inner German border to the Netherlands and Belgium. The terrain clearly favored the attacker. NORTHAG also had the added pressure of protecting the shortest route to the Ruhr, the industrial heartland of West Germany, the West German capital of Bonn, and the shortest routes to Antwerp and Rotterdam, two major ports that played an essential role in flowing reinforcements to NATO.

NATO forces in sector were split between German, British, Dutch and Belgian corps of two to four combat divisions each—meaning it enjoyed unity of command only at the army level. Although NATO could expect quick reinforcement from the UK, the Netherlands and Belgium, most units in the army group’s sector were stationed far from their defensive positions and required extended warning to occupy them.

CENTAG, or Central Army Group, was assigned to the lower half of Germany. CENTAG was a predominantly German and American force, with a mechanized brigade from Canada added for good measure. Two German corps, each with a mix of panzer, panzergrenadier and mountain divisions, would hold the line, as well as two American corps, each consisting of two to three armored and mechanized infantry divisions. CENTAG was responsible for the narrowest point between the German border and the Rhine river, a distance of roughly 120 miles.

Although outnumbered, CENTAG had aces up its sleeve. U.S. and German combat formations were made up of armor and mechanized infantry, ideal for fighting the tank-heavy Soviet and Warsaw Pact forces facing them. Although a conscript army the Bundeswehr, as the West German army was called, was of very high quality, with excellent training, leadership and equipment. American divisions stationed in Europe had an extra maneuver battalion, increasing firepower by approximately 10 percent, and each American corps had an armored cavalry regiment screening the border.

Another plus for CENTAG was the terrain. Unlike northern Germany, the terrain in southern Germany consist of hills, mountains and connecting valleys, all of which strongly favored the defender. It was in CENTAG that the famous Fulda Gap was located, as well as the lesser-known Hof Gap and nearby Cheb Approach.

In the far north, Norway’s shared border with the Soviet Union seemingly boded ill for its defense. The mountainous terrain of Norway, however, made at an attack difficult to sustain, and any Soviet ground assault would have likely been assisted by Soviet marine and airmobile forces. NATO planned to send a multinational brigade, ACE Mobile Force, to buttress Norwegian defenses, and the U.S. Marine Corps pre-positioned an entire brigade’s worth of equipment in Norwegian caves.

Across the continent, NATO could expect enemy airborne landings, helicopter-borne air assaults and attacks by special forces. These light and highly mobile formations would be used to seize key objectives behind NATO lines including airfields, bridges (especially over the Rhine, Main and Weser rivers), headquarters, supply depots and pre-positioned stocks of American equipment.

Guarding against these attacks and providing rear-area security were twelve brigade-sized units of West German reservists. Bonn also had three brigades of paratroops that could be quickly rushed to defend threatened areas. Air base security in NATO was very high, with the U.S. Air Force deploying large numbers of security troops at its many bases and the RAF Regiment guarding British airfields.

If conventional forces failed to stop a Warsaw Pact invasion, NATO had a wide variety of tactical nuclear weapons on hand, from nuclear depth charges to gravity bombs and the Ground-Launched Cruise Missile and Pershing II missiles. While the alliance certainly had enough nuclear weapons to stop a Soviet-led attack, using them would have started a cycle of nuclear retaliation and counter-retaliation difficult to stop. The use of tactical nuclear weapons would likely have begotten the use of strategic nuclear weapons . . . and the end of human civilization.

Orginaly posted on the website, The National Interest in two articles called: How the Warsaw Pact Planned to Win World War Three in Europe and How NATO Planned to Win World War Three in Europe

How the Warsaw Pact Planned to Win World War Three in Europe

Map of Soviet forces in Germany

The scenario is set in the late 1980s, assumed that the forces of the Soviet Union and the rest of the Warsaw Pact—namely East Germany, Poland, Czechoslovakia and Hungary—steamrollered West Germany to defeat NATO. The plan assumed the western alliance would defend as far forward as possible while avoiding the use of tactical nuclear weapons.

But what about the Warsaw Pact? After the Cold War ended, the Polish government made public classified Soviet documents that revealed the likely war plan. The plan, known as “Seven Days to the Rhine,” was the basis of 1979 military exercise that assumed NATO as the aggressor, having nuked a series of twenty-five targets in Poland, including Warsaw and the port of Gdansk. The cover story of countering aggression was a mere fig leaf for the true nature of the anticipated conflict: a bolt-from-the-blue Soviet attack against NATO.

By the 1980s NATO had shifted to a “Flexible Response” nuclear doctrine: the alliance was prepared to use nuclear weapons, but would seek to win the war conventionally. This is in stark contrast to the Warsaw Pact, which saw their use as inevitable and planned to use them from the outset. Such early would confer the pact an enormous strategic advantage over NATO.

In “Seven Days to the Rhine,” Soviet nuclear forces would destroy Hamburg, Dusseldorf, Cologne, Frankfurt, Stuttgart, Munich and the West German capital of Bonn. NATO headquarters in Brussels would be annihilated, as would the Belgian port of Antwerp. The Dutch capital and port of Amsterdam would also be destroyed. Denmark would suffer two nuclear strikes.

1976 map of probable axes of attack for the Warsaw Pact forces into Europe.

The result would be a headless NATO and the destruction or demoralization of civilian governments in West Germany, Belgium, the Netherlands and Denmark—precisely the countries likely to be occupied at the end of the seven days. The elimination of the port cities of Hamburg, Antwerp and Amsterdam would severely curtail NATO’s ability to flow reinforcements from the United Kingdom and North America.

Curiously, France and the United Kingdom were to be spared nuclear strikes. This is probably because both had independent nuclear arsenals not tied to the United States. The United States might have hesitated to retaliate for fear of escalating to strategic nuclear warfare, but for France and the UK the European atomic battlefield was much closer and the dividing line between tactical and strategic not so clear-cut. The Soviet leadership probably had no intention of continuing war with either one on the eighth day.

After the Warsaw Pact had launched nuclear strikes, conventional forces would be sent in to conquer. Seven Days to the Rhine assumed a radioactive zone that used to be called Poland, dividing the Soviet Union from its forces in East Germany, Czechoslovakia and Hungary. Those forces, along with their East German, Czechoslovak and Hungarian counterparts, would need to suffice to carry out the attack. While Polish forces were theoretically available, by 1979 the Soviets would have reason to suspect their political reliability.

As a result, total forces committed would be roughly the same number of forces the pact would have in a no-notice attack on NATO. Planning with the assumption of a radioactive curtain severing forward pact forces from the Soviet Union itself is also a reasonable model for assuming a quick war without a prewar buildup of ammunition and fuel from the Soviet Union.

Leading the spearhead aimed at the heart of NATO would be the Group of Soviet Forces in Germany. The GSFG was comprised of five armies, each with three or four tank and motor-rifle (mechanized infantry) divisions.

In the North, the Soviet and East German attack force would consist of the Soviet Second Guards Tank Army, Twentieth Guards Army and Third Shock Army, consisting of seven tank divisions and five motor rifle divisions. East Germany’s National People’s Army, considered the best of the non-Soviet pact forces, would contribute two tank and four mechanized-infantry divisions.

This combined northern force of eighteen combat divisions, plus artillery, air assault and special forces, would smash into the combined Danish, Dutch, West German, British and Belgian forces facing them. The battle would take place on the so-called North German Plain, a stretch of relatively flat, rolling country from the inner German border to the Low Countries. This was considered the quickest, most direct way to knock out the largest number of NATO countries.

Somewhere in the endless stream of combat vehicles headed west would be what was known as the Operational Maneuver Group, or OMG. Anywhere from two brigades to two divisions large, the OMG would be held in reserve until a breakthrough was achieved. Once committed, the OMG would lunge deep behind enemy lines, cutting off NATO forces as it did so.

In southern Germany, the spearhead would be the Soviet Eighth Guards Army and the First Guards Tank Army, totaling three tank divisions and three motor rifle divisions. The Soviet Central Group of Forces, based in Czechoslovakia, would add two tank and three motor rifle divisions; the Czechoslovak People’s Army would also add three tank and five motor rifle divisions. Czechoslovak forces were formidable in theory, but the Soviets likely still considered them politically suspect twenty years after the Prague Spring of 1968.

This southern force of nineteen divisions would enjoy the shortest route to the Rhine River, only 120 miles as the crow flies, but faced serious military and geographical obstacles. The ten West German and American divisions facing them were among the best-equipped in NATO, and the correlation of forces, to use a Soviet Army phrase, did not favor the attacker. The terrain was a mixture of hills, mountains and connecting valleys, all of which strongly favored the defender.

In the meantime, Soviet airborne and air assault forces would fan out and occupy key bridges, particularly over the Weser and Rhine Rivers. Seizing river crossings would be essential for maintaining the momentum of the ground offensive. Airfields, military headquarters and known alternate seats of government would also be targets. Soviet spetsnaz special forces would also target NATO tactical nuclear weapons, seeking to neutralize Pershing II, Ground Launched Cruise Missiles and nuclear gravity bombs before they could be used.

At sea, the Soviet Navy would immediately go on the offensive. The Soviet Navy would, like the German Navy before it, try to sever the naval supply line from North America to Europe. The Soviet Navy would also immediately try to destroy American aircraft carriers, which with their airborne nuclear weapons were a wild card, capable of delivering nuclear strikes against a variety of targets over vast ranges.

The most important goal of the Soviet Navy would be to safeguard its ballistic missile submarines hiding in the Barents Sea bastion. Whether or not Moscow won or lost in the conventional realm, this would preserve a second-strike strategic capability against the United States. If the Americans were successful in wiping out Soviet boomers, that could embolden them to launch a nuclear first strike.

Warsaw Pact aviation was to be very busy. Assuming a short seven-day war, there would not be time to execute a proper air-defense suppression campaign. Much of NATO’s leadership would have been killed during the nuclear attacks, and as a result NATO air defenses would be disorganized. Pact air forces might simply press on without attempting to destroy NATO air defenses.

Assuming a no-notice war, most combat missions would be preplanned counter-air missions and air strikes against known airfields, army bases and NATO ground positions. Prepositioned stocks of U.S. Army equipment in Germany and the Netherlands would be particularly vulnerable, allowing the pact to knock out entire divisions without fighting them.

The Warsaw Pact plan makes clear two things. First, in a surprise attack, the most important forces are the ground forces. The quicker they can advance, the sooner they can overrun NATO—and that includes air bases and naval facilities. The faster they can force West Germany to surrender, the sooner the rest of NATO runs out of reasons to continue fighting—and the specter of all-out nuclear war recedes.

Second, NATO would have lost the war. NATO’s assumption that the war would gradually escalate to nuclear weapons would have been fatal against an adversary that planned to use them on Day One. The use of nukes in Western Europe would devolved the decision to employ them away from NATO as a collective body to heads of the United States, France and the UK. All three would be forced to use battlefield nukes to save their troops—and risk escalation that would devastate their homelands—or walk away from the rest of NATO.

While the World War III scenario in Europe was always unlikely, it was also the most dangerous. We now know that, instead of an escalation to nuclear war being a possibility, it was virtually guaranteed. The only question would have been to what extent—and whether or not human civilization would have survived it.

How NATO Planned to Win World War Three in Europe

Map of NATO and Warsaw Pact forces in Europe

The North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO) was formed in 1949 to oppose Soviet expansionism in Western Europe. The end of the war saw the Soviet Union solidify its gains in Eastern Europe, garrisoning countries such as Poland, Hungary, Czechoslovakia, Romania, Bulgaria and East Germany. NATO was a direct response to the raising of what Winston Churchill deemed the “Iron Curtain.”

At the time, American and Western European planners felt that if war were to break out between West and Stalin’s Russia, it would quite logically take place in Europe. The reality of nuclear weapons, however, meant that the two sides avoided direct confrontation and instead fought a series of proxy wars worldwide. That having been said, for the Soviet Union an invasion of Western Europe carried the biggest risk—and the biggest reward.

NATO’s strategic mission was to prevent the destruction of the alliance by military force. Essential to that were four wartime goals: gaining air superiority, keeping sea lines of communication open to North America, maintaining the territorial integrity of West Germany and avoiding the use of nuclear weapons. Were NATO to lose any of these four, the war was as good as over.

In 1988, NATO’s plan for the defense of Western Europe was the doctrine of forward defense, in which Soviet and Warsaw Pact forces were stopped as far close to the inner German border as possible. A defense in depth—which experience on the Eastern Front in World War II had proved superior—would have imperiled virtually the entire West German population and forty years of postwar rebuilding.

NATO seemingly had no unified battle plan other than to “man the line” until Soviet and Warsaw Pact forces were exhausted—whereupon counterattacks could be executed to restore prewar borders. West German Army forces, inflexible at the strategic level, were allowed a level of flexibility at the tactical level. The United States devised AirLand Battle, a doctrine that stipulated ground and air units would work together to strike the enemy simultaneously, from the forward edge of the battle area to deep behind enemy lines.

At sea, the primary mission of NATO’s naval forces was to keep the sea lanes between North America and Europe open, in order to guarantee the flow of reinforcements from the United States and Canada. NATO patrol aircraft, ships and submarines would seek out Soviet submarines attempting to interdict supply convoys, trying to keep them north of an imaginary line connecting Greenland, Iceland and the United Kingdom.

In the Norwegian Sea, the U.S. Navy planned to surge two to three carrier battle groups, plus a battleship surface action group to attack Soviet air and naval bases of the Northern Fleet. This direct attack on the Soviet homeland was meant to divert enemy attention from the convoys, destroy air and naval facilities, and starve enemy units at sea of support. It would also, unofficially, isolate Soviet ballistic missile submarines from their land-based support, leaving them in a position to be hunted down.

NATO naval forces would bottle up Soviet, Polish and East German naval forces inside the Baltic Sea, and prevent a seaborne invasion of Denmark. West German naval forces would be on alert for Polish marine units attempting to execute a landing north of Hamburg.

In the air, NATO’s air fleets would be assigned to several roles. American F-15s and F-16s, British Tornado ADV, and German F-4 Phantom jets, among many others, would attempt to establish air superiority over the continent. Meanwhile, British and German Tornado IDS low-level strike bombers would fly counter-air missions, bombing Warsaw Pact airfields in East Germany and Poland. USAF F-111 fighter bombers and other alliance strike jets would perform interdiction missions, bombing bridges, headquarters, supply and other targets to slow the Warsaw Pact advance. Finally, American A-10 Warthogs, German Alpha Jets and Royal Air Force Harriers would be providing forward air support to beleaguered NATO ground troops.

Yet it was on the ground was where the war would have been decided. Everything supported the war on the ground—even the air war, for the ideal Soviet solution to NATO air superiority was to put a tank on every enemy airfield.

Technologically, NATO ground forces had an edge, and the decade was a period where many combat systems were introduced that are still in service today. In 1988, the Europe-based U.S. Seventh Army was several years into fielding its “Big Five” combat systems: the M1 Abrams tank, M2 Bradley infantry fighting vehicle, AH-64 Apache attack helicopter, UH-60 Blackhawk transport and Patriot air defense missile, which would greatly upgrade the Army’s ability to fight AirLand Battle. West Germany had begun deploying its second generation tank, the Leopard II, also being deployed by the Netherlands, and had the Marder infantry combat vehicle. At the same time, the introduction of the Challenger tank and Warrior infantry fighting vehicle reinvigorated the British Army of the Rhine’s combat formations.

NORTHAG, or Northern Army Group, was assigned to the north half of West Germany. NORTHAG was committed to defending the North German Plain, a stretch of relatively flat, rolling country from the inner German border to the Netherlands and Belgium. The terrain clearly favored the attacker. NORTHAG also had the added pressure of protecting the shortest route to the Ruhr, the industrial heartland of West Germany, the West German capital of Bonn, and the shortest routes to Antwerp and Rotterdam, two major ports that played an essential role in flowing reinforcements to NATO.

NATO forces in sector were split between German, British, Dutch and Belgian corps of two to four combat divisions each—meaning it enjoyed unity of command only at the army level. Although NATO could expect quick reinforcement from the UK, the Netherlands and Belgium, most units in the army group’s sector were stationed far from their defensive positions and required extended warning to occupy them.

CENTAG, or Central Army Group, was assigned to the lower half of Germany. CENTAG was a predominantly German and American force, with a mechanized brigade from Canada added for good measure. Two German corps, each with a mix of panzer, panzergrenadier and mountain divisions, would hold the line, as well as two American corps, each consisting of two to three armored and mechanized infantry divisions. CENTAG was responsible for the narrowest point between the German border and the Rhine river, a distance of roughly 120 miles.

Although outnumbered, CENTAG had aces up its sleeve. U.S. and German combat formations were made up of armor and mechanized infantry, ideal for fighting the tank-heavy Soviet and Warsaw Pact forces facing them. Although a conscript army the Bundeswehr, as the West German army was called, was of very high quality, with excellent training, leadership and equipment. American divisions stationed in Europe had an extra maneuver battalion, increasing firepower by approximately 10 percent, and each American corps had an armored cavalry regiment screening the border.

Another plus for CENTAG was the terrain. Unlike northern Germany, the terrain in southern Germany consist of hills, mountains and connecting valleys, all of which strongly favored the defender. It was in CENTAG that the famous Fulda Gap was located, as well as the lesser-known Hof Gap and nearby Cheb Approach.

In the far north, Norway’s shared border with the Soviet Union seemingly boded ill for its defense. The mountainous terrain of Norway, however, made at an attack difficult to sustain, and any Soviet ground assault would have likely been assisted by Soviet marine and airmobile forces. NATO planned to send a multinational brigade, ACE Mobile Force, to buttress Norwegian defenses, and the U.S. Marine Corps pre-positioned an entire brigade’s worth of equipment in Norwegian caves.

Across the continent, NATO could expect enemy airborne landings, helicopter-borne air assaults and attacks by special forces. These light and highly mobile formations would be used to seize key objectives behind NATO lines including airfields, bridges (especially over the Rhine, Main and Weser rivers), headquarters, supply depots and pre-positioned stocks of American equipment.

Guarding against these attacks and providing rear-area security were twelve brigade-sized units of West German reservists. Bonn also had three brigades of paratroops that could be quickly rushed to defend threatened areas. Air base security in NATO was very high, with the U.S. Air Force deploying large numbers of security troops at its many bases and the RAF Regiment guarding British airfields.

If conventional forces failed to stop a Warsaw Pact invasion, NATO had a wide variety of tactical nuclear weapons on hand, from nuclear depth charges to gravity bombs and the Ground-Launched Cruise Missile and Pershing II missiles. While the alliance certainly had enough nuclear weapons to stop a Soviet-led attack, using them would have started a cycle of nuclear retaliation and counter-retaliation difficult to stop. The use of tactical nuclear weapons would likely have begotten the use of strategic nuclear weapons . . . and the end of human civilization.

Orginaly posted on the website, The National Interest in two articles called: How the Warsaw Pact Planned to Win World War Three in Europe and How NATO Planned to Win World War Three in Europe

If that is an accurate depiction of actual Soviet plans as opposed to Warsaw Pact propaganda then any attack would have lead to the destruction of at the least much of centra/western Europe. Possibly far more.

If that is an accurate depiction of actual Soviet plans as opposed to Warsaw Pact propaganda then any attack would have lead to the destruction of at the least much of centra/western Europe. Possibly far more.