Post by lordroel on Jul 14, 2016 14:56:48 GMT

Exercise Armageddon, also described as Operation Armageddon was a plan by the Republic of Ireland drafted at the start of the Troubles in September–October 1969 that envisaged a military invasion and guerrilla operations in Northern Ireland, in order to protect Irish nationalists there from sectarian attack.

'Operation Armageddon' would have been doomsday - for Irish aggressors

The Defense Forces’ plans to invade Northern Ireland, which were drawn up 40 years ago as violence there erupted, display a mixture of enthusiasm and naivety that would have provoked massive retaliatory action from the British . . . had they been implemented.

FORTY-SEVEN YEARS ago, in August and September of 1969, intense rioting and civil unrest prevailed throughout Northern Ireland.

As the violence reached fever pitch the then taoiseach, Jack Lynch, made a televised speech to the nation on RTÉ in which he used the now immortal and much misquoted phrase: “We will not stand by”.

For almost 47 years, historians and political pundits have argued over the precise meaning of this provocative – and yet somewhat ambiguous phrase. Had Jack Lynch intended to convey the possibility of an Irish Army invasion of Northern Ireland – ostensibly to protect nationalists from sectarian attacks?

Unlikely as it may seem today, the Irish Army did indeed draw up secret plans to invade the six counties.

In a secret Irish Army document, drawn up in September 1969 and entitled Interim Report of Planning Board on Northern Ireland Operations– the Irish military authorities explicitly outlined their concept for “feasible” military operations within the six counties.

In its opening paragraphs, the military document – seen by The Irish Times– predicts with considerable understatement that “all situations visualised [in this document] assume that military action would be taken unilaterally by the Defense Forces and would meet with hostility from Northern Ireland Security Forces”.

In other words, due to the prospect of confronting far superior forces and being exposed to “the threat of retaliatory punitive military action by UK forces on the Republic”, Irish military operations would of necessity commence unannounced – with no formal declaration of war.

The document sets out various attack scenarios whereby the Irish general staff would seek to exploit the element of surprise to launch both covert unconventional or guerrilla-style operations against the British authorities, along with conventional infantry attacks on Derry and Newry.

Before elaborating in detail on the precise nature of such offensive operations within Northern Ireland, the authors of this secret document provide a health warning of sorts to their political masters.

At paragraph 4, a statement is made that “The Defense Forces have no capability of embarking on unilateral military operation of any kind . . . therefore any operations undertaken against Northern Ireland would be militarily unsound”.

However, despite this caveat, the document goes on to outline “accepting the implications of subparagraph 4a . . . conventional military operations on a small scale up to a maximum of company level and unconventional operations could be undertaken by the Defence Forces” – subject to such action being of short duration.

At paragraph 4, sub-paragraph g of this extraordinary document, the Irish Army goes on to identify the towns of “Derry, Strabane, Enniskillen and Newry” as most suitable for infantry operations “by virtue of their proximity to the Border” – and also by virtue of their predominantly nationalist demographics.

At sub-paragraph h, the Irish military authorities identify the BBC TV studios in Belfast as a primary target for destruction along with “Belfast airport, docks and main industries . . . located in the northeast corner”. The document observes that due to their “distance from the Border . . . any military operations against these (targets) should preferably be of the unconventional type”.

The remainder of the 18 pages of secret documents dealing with “Northern Ireland Operations” and “Planning for and conduct of Border operations”, also seen by The Irish Times, deal with the steps necessary for the execution of specific – albeit limited – military operations against Newry, Derry and major infrastructural targets in Belfast.

The document outlines at paragraph 23b the requirement for four infantry brigades to be brought up to strength and trained intensively to “operate in company groups” against urban targets – in other words, company-sized attacks on RUC, B Special and British Army elements in Derry and Newry.

At paragraph 23c the document also outlines the requirement for three motorised cavalry squadrons to be fully equipped and brought up to strength – presumably for armoured reconnaissance and lightning strikes on Northern Ireland security forces located in urban areas such as Derry and Newry.

At paragraph 23d, the document recommends the establishment of “a Special Forces Unit, prepared for employment, primarily on unconventional operations”.

At the time that this document was drafted, in September 1969, the Irish Army was seriously under-strength, with a total of 8,113 personnel. While individual troops were relatively well armed with FN 7.62 automatic rifles – purchased for service in the Congo – the Irish Army was severely lacking in transport and other support elements necessary for combat operations, however limited in scale.

At one point in the military document, it is suggested that “CIÉ buses” would have to be commandeered to get Irish troops into action against Border targets. The Irish did have some artillery support – mainly 120mm mortars and second World War vintage 25-pound field guns.

However, the Irish had little or no air support – the Air Corps possessed approximately a half dozen serviceable De Havilland Vampire jets in the autumn of 1969. These aircraft would have been of little use against RAF Phantom and Harrier jets, stationed at that time within a very short flight time from Northern Irish air space.

In terms of ground forces, in September 1969, the British army presence in Northern Ireland was already on high alert and consisted of almost 3,000 heavily armed troops of the 2nd Queens Regiment, the Royal Regiment of Wales and the Prince of Wales’s Own Regiment based in Belfast, Omagh and Derry. These units had – unlike their Irish counterparts – considerable experience and training in conventional large-scale combat tactics as part of Nato’s UK 16 Para Brigade.

Many of these units had just recently rotated to Northern Ireland following deployment as part of Europe’s Nato Northern Flank Mission.

Armed with Humber armored personnel carriers – equipped with Rolls Royce six- cylinder engines – along with Saracen armored fighting vehicles and overwhelming air superiority, the British army presence in Northern Ireland in the autumn of 1969 would have been more than capable of dealing decisively with any Irish Army incursion north of the Border.

Irrespective of the element of surprise, the Irish Army would have been subject to a massive British counter-attack – probably within hours of their initial incursion. Irish casualties would have been high as the British would have sought to swiftly and indiscriminately end the Republic’s unilateral military intervention – which would have had the potential to completely destabilize Northern Ireland, leading perhaps to the type of sectarian violence and ethnic cleansing seen in central Europe just two decades later.

In the final paragraph of the document, the Irish military authorities warn of the doomsday scenario that the aptly named Operation Armageddon might bring about for the Irish Republic – if launched by Lynch’s government.

“Sustained operations of this nature would demand the total commitment of the State . . . Should the operation miscarry, the consequences could be very grave for the State and the people it is intended to assist.”

Luckily for the Irish Republic – and the people of Northern Ireland – Lynch’s declaration not to stand by never translated into a declaration of war.

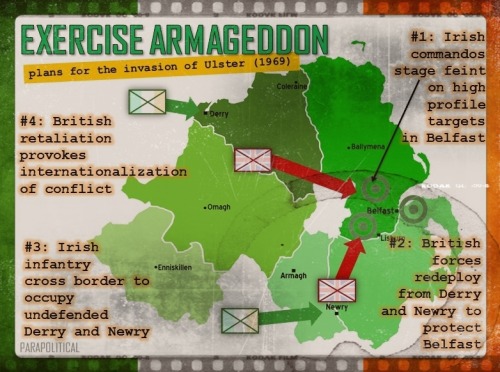

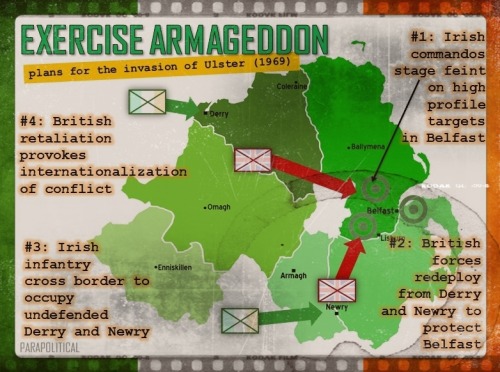

The image below gives an accurate round up of what the plans were for Operation Armageddon

Other articles related to Operation Armageddon

Wikipedia article related to Operation armageddon

Background

Article on Wikipedia related to the Northern Ireland riots of August 1969

The Northern Ireland Civil Rights Association organised protest marches from 1968 seeking to improve conditions for Roman Catholics in Northern Ireland, who were discriminated against by the majority Protestant population. This had led to counter-protests and then sectarian riots, leading to 1,500 Catholic refugees fleeing to the Republic of Ireland. On 13 August 1969 the Taoiseach, Jack Lynch said in a television interview: "...the Irish government can no longer stand by and see innocent people injured and perhaps worse". His cabinet was divided over what to do, with Kevin Boland and Neil Blaney calling for robust action. On 30 August Lynch ordered the Irish Army Chief of Staff, General Seán Mac Eoin, to prepare a plan for possible incursions.

While the riots continued, the introduction of British Army troops in the Falls area of Belfast, and around the Bogside part of Derry from mid-August under Operation Banner protected Catholic areas from further mass loyalist attacks.

The plan

The army's planners accepted that it had "no capability to engage successfully in conventional, offensive military operations against the security forces in Northern Ireland" to protect the Catholic minority from loyalist mobs.

The plan called for units of specially trained and equipped Irish commandos to infiltrate Northern Ireland and launch guerrilla-style operations against the Belfast docks, Aldergrove airport, the BBC studios and key industries. The campaign would start in Belfast and the northwest, so as to draw the bulk of security forces in Northern Ireland away from the border areas and turn their attention to the guerrilla campaign. The Irish Army would then invade with four brigades operating in company-strength units to occupy the Catholic-majority towns of Derry and Newry, and attack[citation needed] any remaining security forces in those areas. The Irish Army Transport Corps did not have enough resources to transport all of the necessary forces to the conflict zone, and the plan suggested hiring buses from CIÉ. For political reasons, the Republic would not formally declare war when the operation started.

Only 2,136 troops out of 12,000 in the army were at actual combat readiness. The operation would leave the Republic of Ireland exposed to "retaliatory punitive military action by United Kingdom forces". The plan included a warning that: "The Defense Forces have no capability of embarking on unilateral military operation of any kind ... therefore any operations undertaken against Northern Ireland would be militarily unsound."

Some theories mention in the documentary

- The plan to occupy Newry would not save any Catholic refugees, as it was a predominantly Catholic town with no inter-sectarian riots.

- The Catholic parts of Derry had suffered assaults from the Royal Ulster Constabulary and Protestant mobs, but was effectively ring-fenced on the introduction of British troops in August; as of October 1969, further attacks were unlikely.

- The plan ignored the incompatibility of forces. The United Kingdom was a member of NATO, while the Irish Defence Forces were much smaller than the British Armed Forces, had inferior arms and transportation in comparison to British forces, and had only minimal air and naval capabilities. The Defense Forces were said to train for "World War II operations using World War I weapons", such as the Lee–Enfield rifle, although most Irish soldiers were armed with FN FAL 7.62 automatic rifles. Former Irish officers such as Vincent Savino recalled that the Irish Army was "so short of the basics", having been allowed to run down since 1945 by the same politicians who now wanted it to undertake such a dangerous mission. By contrast, British forces in Northern Ireland consisted of almost 3,000 heavily armed soldiers of the 2nd Queens Regiment, the Royal Regiment of Wales, and the Prince of Wales's Own Regiment of Yorkshire. These troops had considerable experience in training and conventional large-scale combat tactics, and many had returned from guarding NATO's Northern Flank. They were equipped with Humber Pig and Saracen armored personnel carriers. Royal Air Force F-4 Phantom and Harrier jets were also stationed at airbases within short flying time from Northern Ireland. These forces would have been capable of dealing decisively with any Irish military incursion into the area. The mismatch was reflected in the choice of title. According to security analyst Tom Clonan, "irrespective of the element of surprise, the Irish Army would have been subject to a massive British counterattack - probably within hours of their initial incursion. Irish casualties would have been high as the British would have sought to swiftly and indiscriminately end the Republic's unilateral military intervention".

- In 1969, both the Republic and the UK were applying to join the European Economic Community. The Republic's application would likely have been jeopardised if it had invaded a "friendly neighbour".

- While the Irish government had called for United Nations involvement in Northern Ireland in August 1969, launching a localised but technical invasion and then calling again for intervention would have led to universal condemnation, being contrary to international law. The Republic of Ireland had joined the UN only in 1955.

- All members of NATO are bound by the North Atlantic Treaty to oppose a military incursion on a member state; this would probably force the United States to intervene.

- The targets for covert operations, such as the BBC offices in Belfast, were already guarded by the British Army to protect them from local rioters. None of these targets were linked to the inter-sectarian riots.

- An intrusion might have provoked new and more widespread sectarian rioting, causing hundreds of deaths.

- An invasion of Northern Ireland by the armed forces of the Republic would likely have met with the same overwhelmingly negative international response as the UK's invasion of the Suez Canal zone during the Suez Crisis in 1956.

- There was a high chance that the British would counter the invasion with a counter-invasion of the Republic, most likely resulting in the capitulation of the Republic to UK forces in a hypothetical retaliatory invasion and occupation.

'Operation Armageddon' would have been doomsday - for Irish aggressors

The Defense Forces’ plans to invade Northern Ireland, which were drawn up 40 years ago as violence there erupted, display a mixture of enthusiasm and naivety that would have provoked massive retaliatory action from the British . . . had they been implemented.

FORTY-SEVEN YEARS ago, in August and September of 1969, intense rioting and civil unrest prevailed throughout Northern Ireland.

As the violence reached fever pitch the then taoiseach, Jack Lynch, made a televised speech to the nation on RTÉ in which he used the now immortal and much misquoted phrase: “We will not stand by”.

For almost 47 years, historians and political pundits have argued over the precise meaning of this provocative – and yet somewhat ambiguous phrase. Had Jack Lynch intended to convey the possibility of an Irish Army invasion of Northern Ireland – ostensibly to protect nationalists from sectarian attacks?

Unlikely as it may seem today, the Irish Army did indeed draw up secret plans to invade the six counties.

In a secret Irish Army document, drawn up in September 1969 and entitled Interim Report of Planning Board on Northern Ireland Operations– the Irish military authorities explicitly outlined their concept for “feasible” military operations within the six counties.

In its opening paragraphs, the military document – seen by The Irish Times– predicts with considerable understatement that “all situations visualised [in this document] assume that military action would be taken unilaterally by the Defense Forces and would meet with hostility from Northern Ireland Security Forces”.

In other words, due to the prospect of confronting far superior forces and being exposed to “the threat of retaliatory punitive military action by UK forces on the Republic”, Irish military operations would of necessity commence unannounced – with no formal declaration of war.

The document sets out various attack scenarios whereby the Irish general staff would seek to exploit the element of surprise to launch both covert unconventional or guerrilla-style operations against the British authorities, along with conventional infantry attacks on Derry and Newry.

Before elaborating in detail on the precise nature of such offensive operations within Northern Ireland, the authors of this secret document provide a health warning of sorts to their political masters.

At paragraph 4, a statement is made that “The Defense Forces have no capability of embarking on unilateral military operation of any kind . . . therefore any operations undertaken against Northern Ireland would be militarily unsound”.

However, despite this caveat, the document goes on to outline “accepting the implications of subparagraph 4a . . . conventional military operations on a small scale up to a maximum of company level and unconventional operations could be undertaken by the Defence Forces” – subject to such action being of short duration.

At paragraph 4, sub-paragraph g of this extraordinary document, the Irish Army goes on to identify the towns of “Derry, Strabane, Enniskillen and Newry” as most suitable for infantry operations “by virtue of their proximity to the Border” – and also by virtue of their predominantly nationalist demographics.

At sub-paragraph h, the Irish military authorities identify the BBC TV studios in Belfast as a primary target for destruction along with “Belfast airport, docks and main industries . . . located in the northeast corner”. The document observes that due to their “distance from the Border . . . any military operations against these (targets) should preferably be of the unconventional type”.

The remainder of the 18 pages of secret documents dealing with “Northern Ireland Operations” and “Planning for and conduct of Border operations”, also seen by The Irish Times, deal with the steps necessary for the execution of specific – albeit limited – military operations against Newry, Derry and major infrastructural targets in Belfast.

The document outlines at paragraph 23b the requirement for four infantry brigades to be brought up to strength and trained intensively to “operate in company groups” against urban targets – in other words, company-sized attacks on RUC, B Special and British Army elements in Derry and Newry.

At paragraph 23c the document also outlines the requirement for three motorised cavalry squadrons to be fully equipped and brought up to strength – presumably for armoured reconnaissance and lightning strikes on Northern Ireland security forces located in urban areas such as Derry and Newry.

At paragraph 23d, the document recommends the establishment of “a Special Forces Unit, prepared for employment, primarily on unconventional operations”.

At the time that this document was drafted, in September 1969, the Irish Army was seriously under-strength, with a total of 8,113 personnel. While individual troops were relatively well armed with FN 7.62 automatic rifles – purchased for service in the Congo – the Irish Army was severely lacking in transport and other support elements necessary for combat operations, however limited in scale.

At one point in the military document, it is suggested that “CIÉ buses” would have to be commandeered to get Irish troops into action against Border targets. The Irish did have some artillery support – mainly 120mm mortars and second World War vintage 25-pound field guns.

However, the Irish had little or no air support – the Air Corps possessed approximately a half dozen serviceable De Havilland Vampire jets in the autumn of 1969. These aircraft would have been of little use against RAF Phantom and Harrier jets, stationed at that time within a very short flight time from Northern Irish air space.

In terms of ground forces, in September 1969, the British army presence in Northern Ireland was already on high alert and consisted of almost 3,000 heavily armed troops of the 2nd Queens Regiment, the Royal Regiment of Wales and the Prince of Wales’s Own Regiment based in Belfast, Omagh and Derry. These units had – unlike their Irish counterparts – considerable experience and training in conventional large-scale combat tactics as part of Nato’s UK 16 Para Brigade.

Many of these units had just recently rotated to Northern Ireland following deployment as part of Europe’s Nato Northern Flank Mission.

Armed with Humber armored personnel carriers – equipped with Rolls Royce six- cylinder engines – along with Saracen armored fighting vehicles and overwhelming air superiority, the British army presence in Northern Ireland in the autumn of 1969 would have been more than capable of dealing decisively with any Irish Army incursion north of the Border.

Irrespective of the element of surprise, the Irish Army would have been subject to a massive British counter-attack – probably within hours of their initial incursion. Irish casualties would have been high as the British would have sought to swiftly and indiscriminately end the Republic’s unilateral military intervention – which would have had the potential to completely destabilize Northern Ireland, leading perhaps to the type of sectarian violence and ethnic cleansing seen in central Europe just two decades later.

In the final paragraph of the document, the Irish military authorities warn of the doomsday scenario that the aptly named Operation Armageddon might bring about for the Irish Republic – if launched by Lynch’s government.

“Sustained operations of this nature would demand the total commitment of the State . . . Should the operation miscarry, the consequences could be very grave for the State and the people it is intended to assist.”

Luckily for the Irish Republic – and the people of Northern Ireland – Lynch’s declaration not to stand by never translated into a declaration of war.

The image below gives an accurate round up of what the plans were for Operation Armageddon

Other articles related to Operation Armageddon

Wikipedia article related to Operation armageddon

Background

Article on Wikipedia related to the Northern Ireland riots of August 1969

The Northern Ireland Civil Rights Association organised protest marches from 1968 seeking to improve conditions for Roman Catholics in Northern Ireland, who were discriminated against by the majority Protestant population. This had led to counter-protests and then sectarian riots, leading to 1,500 Catholic refugees fleeing to the Republic of Ireland. On 13 August 1969 the Taoiseach, Jack Lynch said in a television interview: "...the Irish government can no longer stand by and see innocent people injured and perhaps worse". His cabinet was divided over what to do, with Kevin Boland and Neil Blaney calling for robust action. On 30 August Lynch ordered the Irish Army Chief of Staff, General Seán Mac Eoin, to prepare a plan for possible incursions.

While the riots continued, the introduction of British Army troops in the Falls area of Belfast, and around the Bogside part of Derry from mid-August under Operation Banner protected Catholic areas from further mass loyalist attacks.

The plan

The army's planners accepted that it had "no capability to engage successfully in conventional, offensive military operations against the security forces in Northern Ireland" to protect the Catholic minority from loyalist mobs.

The plan called for units of specially trained and equipped Irish commandos to infiltrate Northern Ireland and launch guerrilla-style operations against the Belfast docks, Aldergrove airport, the BBC studios and key industries. The campaign would start in Belfast and the northwest, so as to draw the bulk of security forces in Northern Ireland away from the border areas and turn their attention to the guerrilla campaign. The Irish Army would then invade with four brigades operating in company-strength units to occupy the Catholic-majority towns of Derry and Newry, and attack[citation needed] any remaining security forces in those areas. The Irish Army Transport Corps did not have enough resources to transport all of the necessary forces to the conflict zone, and the plan suggested hiring buses from CIÉ. For political reasons, the Republic would not formally declare war when the operation started.

Only 2,136 troops out of 12,000 in the army were at actual combat readiness. The operation would leave the Republic of Ireland exposed to "retaliatory punitive military action by United Kingdom forces". The plan included a warning that: "The Defense Forces have no capability of embarking on unilateral military operation of any kind ... therefore any operations undertaken against Northern Ireland would be militarily unsound."

Some theories mention in the documentary

- The plan to occupy Newry would not save any Catholic refugees, as it was a predominantly Catholic town with no inter-sectarian riots.

- The Catholic parts of Derry had suffered assaults from the Royal Ulster Constabulary and Protestant mobs, but was effectively ring-fenced on the introduction of British troops in August; as of October 1969, further attacks were unlikely.

- The plan ignored the incompatibility of forces. The United Kingdom was a member of NATO, while the Irish Defence Forces were much smaller than the British Armed Forces, had inferior arms and transportation in comparison to British forces, and had only minimal air and naval capabilities. The Defense Forces were said to train for "World War II operations using World War I weapons", such as the Lee–Enfield rifle, although most Irish soldiers were armed with FN FAL 7.62 automatic rifles. Former Irish officers such as Vincent Savino recalled that the Irish Army was "so short of the basics", having been allowed to run down since 1945 by the same politicians who now wanted it to undertake such a dangerous mission. By contrast, British forces in Northern Ireland consisted of almost 3,000 heavily armed soldiers of the 2nd Queens Regiment, the Royal Regiment of Wales, and the Prince of Wales's Own Regiment of Yorkshire. These troops had considerable experience in training and conventional large-scale combat tactics, and many had returned from guarding NATO's Northern Flank. They were equipped with Humber Pig and Saracen armored personnel carriers. Royal Air Force F-4 Phantom and Harrier jets were also stationed at airbases within short flying time from Northern Ireland. These forces would have been capable of dealing decisively with any Irish military incursion into the area. The mismatch was reflected in the choice of title. According to security analyst Tom Clonan, "irrespective of the element of surprise, the Irish Army would have been subject to a massive British counterattack - probably within hours of their initial incursion. Irish casualties would have been high as the British would have sought to swiftly and indiscriminately end the Republic's unilateral military intervention".

- In 1969, both the Republic and the UK were applying to join the European Economic Community. The Republic's application would likely have been jeopardised if it had invaded a "friendly neighbour".

- While the Irish government had called for United Nations involvement in Northern Ireland in August 1969, launching a localised but technical invasion and then calling again for intervention would have led to universal condemnation, being contrary to international law. The Republic of Ireland had joined the UN only in 1955.

- All members of NATO are bound by the North Atlantic Treaty to oppose a military incursion on a member state; this would probably force the United States to intervene.

- The targets for covert operations, such as the BBC offices in Belfast, were already guarded by the British Army to protect them from local rioters. None of these targets were linked to the inter-sectarian riots.

- An intrusion might have provoked new and more widespread sectarian rioting, causing hundreds of deaths.

- An invasion of Northern Ireland by the armed forces of the Republic would likely have met with the same overwhelmingly negative international response as the UK's invasion of the Suez Canal zone during the Suez Crisis in 1956.

- There was a high chance that the British would counter the invasion with a counter-invasion of the Republic, most likely resulting in the capitulation of the Republic to UK forces in a hypothetical retaliatory invasion and occupation.