ALTERNATE TIME LINE “RENO’S Greasy Grass ”

Apr 18, 2023 16:28:19 GMT

lordroel, 1bigrich, and 1 more like this

Post by oscssw on Apr 18, 2023 16:28:19 GMT

“RENO’s Greasy Grass ”

BIG thanks to Miletis12 for teaching me how to add images.

No good deed goes unpunished

1804–1806 Lewis and Clark Expedition

1851 First Fort Laramie Treaty

1861–1865 Civil War

1863 June During the Gettysburg Campaign, two regiments of the Michigan Brigade were armed with the Spencer carbine. These cavalry regiments were under Brevet Brigadier General George Armstrong Custer. These reliable repeaters were decisive at the Battle of Hanover and at East Cavalry Field. Brevet Gen. George A. Custer's Michigan Brigade assisted Farnsworth to hold his ground, and a stalemate ensued. Stuart was forced to continue north and east to get around the Union cavalry, further delaying his attempt to rejoin Robert E. Lee's army, which was then concentrating at Cashtown Gap west of Gettysburg. This delay of JEB left Lee Blind during a crucial period of the battle. Custer was very impressed with the Spencer.

1862 Santee Sioux (Minnesota) Uprising

November 29, 1864 Sand Creek Massacre

1866 July 28 Custer was appointed lieutenant colonel of the newly created 7th Cavalry Regiment,

which was headquartered at Fort Riley, Kansas. He served on frontier duty at Fort Riley from

October 18 to March 26, and scouted in Kansas and Colorado until July 28, 1867.

A US Army cavalry regiment consisted of 12 companies formed into 3 squadrons of 4 companies each. Besides the commanding officer who was a colonel, the regimental staff included 7 officers, 6 enlisted men, a surgeon, and 2 assistant surgeons. Each company was authorized 4 officers, 15 noncommissioned officers, and 72 privates. A civilian veterinarian accompanied the regiment although he was not included in the table of organization.

The regiment was armed from late civil war stock of 116,000 Remington .44 caliber, six-shot, cap and ball Model 1863 New Model Army revolvers. The .44 caliber six-shot New Model Army was as reliable, but not as popular, as Colt's revolvers. The checkered walnut grips are factory finished with a medium gloss varnish, mounted with a blued steel screw, through brass escutcheons. The 8" octagon barrel is fitted with a post blade front sight. The notch in the center of the frame serves as the rear sight. The traditional brass triggerguard is polished bright. The Remington trigger is wide and comfortable, and the release is modest, with no creep or lost motion. The troopers were also issued a black leather flapped cross draw(Butt forward) holster, black leather belt with brass buckle, an extra cylinder and nipple wrench.

The 7th was issued from the large stock (90,000) of late Civil War The Spencer repeating carbine carbines. These used the Spencer .56-56 caliber metallic-cartridge; the Army had over 30,000,000 surplus rounds. The Spencer was a repeating, Manually cocked hammer, lever action, 7 round tube magazine. The Spencer had a Rate of fire: 14-20 rounds per minute. Maximum Effective Range was 500 yards in the hands of a good marksmen. Given the US Army allowed only about 20 rounds per year for training, not many first enlistment were marksmen. It was deadly accurate on man-size targets out to 300 yards in the hands of a trained soldier.

1867 Medicine Lodge Treaty of 1867

The army purchased fifty. 50 caliber Gatling guns.

1867 September 16 Custer was arrested and charged with “absence without leave from his command," it was specified that he left Fort Wallace for Fort Harker without proper authority from his superiors. Many of the other specifications fell under the charge of "conduct prejudicial to good order and military discipline." Two of these specifications claimed that he had marched some of his men "upon private business". Behind these charges, however, lay the larger accusation that Custer should have been devoting his time, energy, forces and resources to pursuing Indians.

1867 October 11 Lt. Col Custer was found guilty on all charges and sentenced with suspension of rank and pay for one year.

1868 December 15 Major Marcus Reno joined the 7th Cavalry at Fort Hays, Kansas as XO. Major Reno commanded the 7th Cavalry during Custer's absence. Marcus Reno was born on November 15, 1834, in Carrollton, Illinois. Reno entered West Point on 1 September 1851. He graduated 20th in a class of 38 in June 1857. Reno served in the Union Army during the Civil War, participating in the Battles of Kelly's Ford (wounded), the Gettysburg Campaign, Cold Harbor, Trevilian Station, and Cedar Creek. He was twice brevetted for gallant and meritorious conduct. After the war, Reno served in the Pacific Northwest until 1868.

1868 September 24, two months before his sentence was up, Custer was reinstated to command the 7th US Cavalry once again by General Phillip Sheridan with orders to find and attack the villages of Cheyenne Dog Soldiers.

1868 Second Fort Laramie Treaty

1868 November 27 during “Red Cloud's War” the battle of the Washita occurred near present Cheyenne in Roger Mills County, Oklahoma. Prior to that date, theand military campaigns in western Kansas had failed to stem the tide of Indian raiding on the southern Great Plains. Maj. Gen. Philip H. Sheridan, who had been named commander of the Department of the Missouri in spring 1868, realized that warm weather expeditions against the mounted Southern Cheyenne, Southern Arapaho, and other "hostiles" were ineffective. Therefore, he devised a plan to attack during the winter months when the tribes were encamped and most vulnerable.

In November 1868 three columns of U.S. Army cavalry and infantry troops from forts Bascom in New Mexico, Lyon in Colorado, and Dodge in Kansas, were ordered to converge on the Indian Territory (present Oklahoma) and strike the Southern Cheyenne and the Southern Arapaho. The main force was the Seventh Cavalry led by Lt. Col. George A. Custer. Custer's troops marched from Fort Dodge and established Camp Supply in the Indian Territory, where they were to rendezvous with the Nineteenth Kansas Volunteer Cavalry, which was advancing from Topeka. Slowed by a severe snowstorm, the Nineteenth was unable to reach the post in time, and the Seventh set out alone on November 23.

While Custer's main body of troops and supplies advanced in deep snow south toward the Canadian River and the Antelope Hills, scouts from Maj. Joel Elliott's detachment found an Indian trail further south near the Washita River. Custer reformed the Seventh and decided to follow the path down the Washita, leaving the baggage train to catch up later. The Seventh arrived on a ridge behind an Indian camp after midnight on November 27. After moving forward with his Osage scouts and surveying the area, Custer planned to divide the Seventh into four battalions and attack the village at dawn.

Custer's target was peace chief Black Kettle's camp of about 250 Cheyenne. Earlier, on November 20, 1868, Bvt. Maj. Gen. William B. Hazen, commander of the military's Southern Indian District, had warned Black Kettle, who was seeking protection and supplies for his band at Fort Cobb in the Indian Territory, that the military was pursuing the Cheyenne and the Arapaho. Black Kettle learned that he and his principal men would have to deal with the army's field commanders if they wanted peace. Based on that knowledge, Black Kettle planned to move his village from its present location to larger Cheyenne encampments down the Washita. Having been attacked at Sand Creek in Colorado in 1864, he hoped to find safety in numbers.

Custer's troops were in position by daybreak, and he ordered them forward. Someone from the village spotted the soldiers and fired a shot to warn the camp. The attack started, and within ten minutes the village had been overrun. Fighting continued until about three o'clock that afternoon, however, because Indians from camps downstream rushed up the valley to aid Black Kettle. Arapaho and Kiowa were among those that encountered and killed a detachment of seventeen men led by Maj. Joel Elliott along a stream now known as Sergeant Major Creek. (Arapaho chief Little Raven and the Kiowa Satanta were among the defenders of Black Kettle's village.)

Black Kettle and an indeterminate number of Cheyenne were killed, and fifty-three women and children were captured. (Custer reported 103 Cheyenne men had been killed. The Cheyenne claimed only about eleven of their men had died. The rest were women and children.) In addition, fifty-one lodges and their contents were burned, and the camp's pony herd of roughly eight hundred horses was killed. The Seventh Cavalry suffered twenty-two men killed, including two officers, fifteen wounded, and one missing. That very evening the Seventh, with their prisoners in tow, began their return march to Camp Supply.

1869 The Sheridan-Custer campaign continued, with troopers of the Seventh Cavalry and the Nineteenth Kansas Volunteer Cavalry roaming over much of present southwestern Oklahoma.

Work on Camp Wichita, later Fort Sill, begun, replacing Fort Cobb as a base of operations.

March Custer overtook a large number of Cheyenne on the Sweetwater River in the Texas Panhandle. His supplies exhausted, Custer did not attack. Instead, using trickery, he took tribe leaders hostage and won a Cheyenne promise to report to Camp Supply. Declaring the five-month campaign finished, Custer led his army back to Kansas, and they arrived at Fort Hayes on April 10, 1869.

Custer’s and most of his officers and troopers opinion of the Spencer now included evidence that it was a superb weapon against the plain’s Indians.

1873 Panic of 1873 and recession

1873 Custer and the 7th Cavalry posted to Ft. Abraham Lincoln, Dakota Territory. Custer faced a group of attacking Lakota at the Northern Pacific Railroad Survey at Yellowstone. It was his first encounter with Lakota leaders Sitting Bull and Crazy Horse, but it wouldn’t be his last. Little did Custer know at the time the two Indigenous leaders would play a role in his death a few years later.

Major Reno, along with both ordnance and civil war calvary veterans was on the board of officers involved in the final rejection of the Springfield Model 1873 and decision to continue the late war Spencer as the standard carbine of the US Army.

The major reasons for rejection were:

A. Lack of funding for both a new infantry rifle and Cavalry carbine.

The Ordnance Department had just adopted the Springfield No. 99 as the standard infantry weapon of the U.S. Army. Later designated the Springfield Model 1873 and nicknamed the “Springfield Trapdoor,” the rifle would serve the American military for the next twenty years. The rifle got its nickname from its breech-loading mechanism, which resembled a trapdoor. To load a round, a soldier had to open the latch and manually insert a single cartridge.

B. Poor reliability of the Model 1873 carbine during trials. The Army had yet to switch over to brass cartridges and still relied on copper. Firing the carbine created heat that caused the copper cartridges to expand, making the spent cartridge difficult to extract from the breech. One method to remove it was to pry it out with a knife. The M1873 field manual instructed soldiers to push the cartridge out with a cleaning rod, but this presented a problem since the M1873 carbine was not equipped with a cleaning rod.

C. Civil War experienced cavalry officers valued the volume of fire the spencer could deliver.

Although most of the men drew the standard-issue Spencer’s , it was their prerogative to purchase their own arms. Custer carried a Remington .50-caliber sporting rifle with octagonal barrel. Yellow hair also packed two revolvers that were not standard issue; Webley British Bulldog, double-action, white-handled revolvers.

Captain Thomas A. French of Company M carried a .50-caliber Springfield that his men called “Long Tom.” Sergeant John Ryan, also of Company M, used a .45-caliber, 15-pound Sharps telescopic rifle, specially made for him. Private Henry A. Bailey of Company I had a preference for a Dexter Smith, breech loading, single-barreled shotgun.

7th Cavalry issued Colt M1873 Cavalry model 7½ inch barrel, single action, six shot, solid frame revolver. Chambered in .45 Colt (also known as .45Long Colt or .45LC). The Colt Single Action Army revolver was chosen over other Colts, Remington and Starrs. By 1871, the percussion cap models were being converted for use with metallic cartridges. Ordnance testing in 1874 narrowed the field to two final contenders: the Colt Single Action Army and the Smith & Wesson Schofield. The Schofield won only in speed of ejecting empty cartridges. The Colt won in firing, sanding and rust trials and had fewer, simpler and stronger parts. It had a muzzle velocity of 810 feet per second, with 400 foot-pounds of energy. Its effective range dropped off rapidly over 60 yards, however. The standard U.S. issue of the period had a blue finish, case-hardened hammer and frame, and walnut grips.

1875 May A delegation of Lakota chiefs came to the White House to protest shortages of government rations and the greed of a corrupt Indian agent. Grant seized the opportunity to:

First, he said, the government’s treaty obligation to issue rations had run out and could be revoked; rations continued only because of Washington’s kind feelings toward the Lakota.

Second, he, the Great Father, was powerless to prevent miners from overrunning the Black Hills (which was true enough, given limited Army resources). The Lakota. must either cede the Paha Sapa ( Lakota for Black Hills) or lose their rations.

When the chiefs left the White House for three weeks they alternated between exasperating encounters with threatening bureaucrats and bleak hotel-room councils among themselves. At last, they broke off the talks and returned to the reservation disgusted and very, very angry.

December 3, 1875 Lakota and Cheyenne 'wanderers' ordered back to their reservations

January 31, 1876 Deadline for the Lakota and Cheyenne to return to their reservations

February 1, 1876 Off-reservation Indians certified hostile; matter handed to War Department

February 2, 1876 Pursuant to orders issued by Terry the Military Department of Dakota detailed two officers and 24 enlisted men of the 20th Infantry for special duty in a Gatling gun battery, equipped with the improved magazine system to be organized at Fort Lincoln.

February 20, 1876 After a perilous snowbound train ride from their stations in Dakota Territory and Minnesota, 2nd Lt. William H. and his men arrived at the fort. Custer was away combining, at the government’s expense, a holiday with Libby in Washington and testifying before a Congressional committee investigating allegations of corruption in President Ulysses S. Grant’s administration. Before his departure the post commander issued orders for Low to organize and drill a “battery consisting of four pieces.” Because eight men manned each gun, Terry subsequently authorized the assignment of eight additional men from Low’s regiment to the special unit.

The army purchased fifty. 50 caliber Gatling guns in 1867. These new guns were not apparently in use on the frontier for some time, as no record of their use appeared for some time after their purchase. The development and adoption of the .50 center fire metallic cartridge by the army furnished the type of ammunition needed for the Gatling gun and the army first rapid fire or machine gun was placed in service. The gun consisted of ten barrels mounted around a c central axis and operated by turning a hand crank at the breech, which h caused the barrels to revolve around the axis . Each complete revolution of the crank brought each of the ten barrels in line with the stationary breech, which caused the bottom barrel to fire and the top one to eject the empty shell as the mechanism is m was operated .

The ammo was introduced at the top by means of a gravity feed hopper, and the only limitations on firing , theoretically , were the ability of the operator to turn the crank rapidly and the speed with which the loader replaced the empty magazines. Thus, if the operator could revolve the mechanism one hundred times a minute and the loader keep the supply of cartridges constant, the gun could deliver one thousand bullets a minute. Even though the army brass was never happy with the earlier Manual manipulation allowed cartridges from one stack to drop down into the gun at a time. The army ordnance bureau had refused to modify it’s gatlings in 1871 to use a true early box magazine to replaced the 40 round tins.

However, in 1872, an influential Indianapolis, Indiana congress and former Army of the Potomac Col of volunteers and friend of Phil Sheridan talked the Army Ordnance board into attending a demonstration of the Gatling Company (which was produced in Indianapolis) newly patented improved type of feed device named after L. M. Broadwell. The Broadwell Drum consisted of twenty stacks of cartridges arrayed in a circle with the bullets pointing inward at a central column (kind of like the later Lewis drum). Each stack held twenty rounds, giving the drum a total capacity of 400 rounds. Not only did the new drum vastly improve the effective rate of fire, it did it with far less jams.

The Gatling gun had been considered an artillery weapon, usually mounted on a light field artillery carriage. However the 40 round magazines and a tendency to jamming, as much due to the feed as to the lack of practice by the gun crews, had long supported the traditional conservatism of the board of Accordance in it’s objection to wide scale purchase and use of the gatling. Now a majority of the board, including the Chief of Ordnance believed the gun hat matured enough to be of real value in repulsing Indian charges and as an offensive weapon for use with infantry.

Three months later the board got a report from the Springfield Arsenal that the modifications to the 1867 guns to accommodate the Broadwell Drum were minor, cheap and easily reservable more than half were impressed. The board met two weeks later under, the urging of the same congressman, to consider the Gatling Company’s proposal to provide the necessary parts to the Springfield Armory at very reasonable cost IF the army signed a contract for an initial purchase of 200 drums. The contract contained a clause that IF the army found that, under field conditions, the Broadwell Drum drums proved unsatisfactory the company would refund both the cost of the drums and the replacement parts.

.

March 1, 1876 Crook's Wyoming column departs Fort Fetterman, Wyoming Territory

March 17, 1876 Colonel Reynolds attacks Cheyenne camp on the Little Missouri River

April 3, 1876 Gibbon's Montana column departs Fort Ellis, Montana Territory

April 12 1876 Custer returns from Washington DC after an attempt to mollify POTUS Grant but his old commander refused to meet with him. Grant's reason for avoiding Custer was political. Custer had testified about corruption in Grant's Indian affairs offices, so Grant removed him from command. Despite his better judgment, Grant's wartime friend Phillip Sheridan, persuaded him to send Custer West and restore his command of the 7th Cavalry. Custer was now determined to restore his fortunes and career by the only means he knew; on the field of battle.

Grant knew “Goldie Locks” all too well and, despite his great respect for his dear friend Sheridan, took steps to control Custer. Grant sent an “Eyes only letter” to Terry by special messenger. He made it quite clear that he had grave doubts about Custer in the upcoming campaign. He ordered Terry to keep “The Boy General” on a very short leash with very specific orders in writing that could not be misinterpreted. Terry was to relieve Custer of his command at the first sign of insubordination, shaking off authority, recklessness or even unruly talk.”

Grant just knew, given the slightest chance, the “Glory Hunting Bastard” would do something rash and very dangerous to restore his image and future prospects. He ended the private message with the threat to “End your career if Custer Kicked over the traces”.

May 10 , 1876 Low , with the agreement of his battery Sgt, a former captain of Volunteer artillery veteran during the civil War reduced his Gatling Gun detachment to 3 pieces for this campaign. By pooling the best horses in the battery they both believed they could, in all good conscience, could keep up with the column. Custer wanted to leave the entire battery behind but only Terry could authorize that.

Custer made the case to Terry that both the 7th Cavalry and the battery lacked adequate horsepower. He also contended the shortage of serviceable horses further restricted the mobility of Low’s Gatling guns (viewed by the Army as a defensive tactical weapon) and he could better use the serviceable horses to better mount his troopers. Terry agreed to the reduction to three Gatlings and told Custer he would see what he could do about remounts for the 7th. .

For Custer the shortage of adequate mounts would reduce the strength of his command, forcing him to leave the regimental band, many recruits and other dismounted troopers at the Powder River supply depot when the regiment pursued the Indians up Rosebud Creek that June.

May 17, 1876 Terry's Dakota column departs Fort Lincoln, Dakota Territory

Brigadier General Terry commanded two companies of the 7th US Infantry, one company of the 6th US Infantry, Low’s Gatling Gun detachment and the entire 7th Cavalry, numbering in all about 925 men.

Alfred Terry was one of the best Union generals and the military commander of the Dakota Territory from 1866 to 1869 and again from 1872 to 1886. He was born in 1827 in Hartford, Connecticut, to a prosperous family. Having a good education, he became a lawyer and was appointed as the Superior Court of New Haven County clerk in the 1850’s.

At the outbreak of the Civil War, Terry raised a regiment of Connecticut volunteers and led them into battle at First Bull Run and other engagements in Virginia, the Carolinas, and Georgia. His success on the battlefield earned him a promotion to brigadier general.

In 1866, Terry became military commander of the Department of Dakota and would play an essential role in the army’s long and often ruthless campaign against the Indians to gain control of the northern plains. In 1867, he served as a member of the peace commission that finally ended Red Cloud’s attacks by negotiating the Fort Laramie Treaty of 1868. Terry’s legal training and judicial experience would lead to his selection for many similar commissions throughout his career.

29 May, 1876 Crook's Wyoming column departs Fort Fetterman

June 2, 1876 after a staff meeting Custer requested a private word with his commander. Terry thinking about Grant’s letter was wary but consented. Once again Custer was pressing Terry to send the Gatling gun detachment of the 20th Infantry under 2nd Lt. William H. Low, back to Powder River supply depot and mount the men he left there due to lack of mounts. Custer “pleaded” that amounts to three gun teams and six limbers teams along with the mounted gunners added up to 180 horses or two full strength troops of cavalry. This twas a new tack for Custer’s argument.

In the past he had argued saying that the battery “might embarrass him, and that he was strong enough without it. Or “They might hamper our movements or march at a critical moment, because of the inferior horses and of the difficult nature of the country.”

Terry knew the majority of the dismounts were Custer’s band and raw recruits. He also believed Custer valued his band a lot more than Low’s guns. Once again he turned Custer down.

June 4–7, 1876 Sitting Bull's Sun Dance

The region containing the Powder, Rosebud, Bighorn, and Yellowstone rivers was a productive hunting ground and the tribes regularly gathered in large numbers during early summer to celebrate their annual sun dance ceremony. During the ceremony, Sitting Bull received a vision of soldiers falling upside down into his village. He prophesied there soon would be a great victory for his people.

Sitting Bull and Crazy Horse were Battle-Hardened War leaders

In 1873, Custer faced a group of attacking Lakota at the Northern Pacific Railroad Survey at Yellowstone. It was his first encounter with Lakota leaders Sitting Bull and Crazy Horse, but it wouldn’t be his last. Little did Custer know at the time the two Indigenous leaders would play a role in his death a few years later.

In 1868, the U.S. government had signed a treaty recognizing South Dakota’s Black Hills as part of the Great Sioux Reservation. However, the government had a change of heart and decided to break the treaty in 1874 when Custer led an excursion of miners who had been looking for gold into the Black Hills.

Custer was tasked with relocating all Native Americans in the area to reservations by January 31, 1876. Any person who didn’t comply would be considered hostile.

The Native Americans, however, didn’t take the deception lying down. Those who could, left their reservations and traveled to Montana to join forces with Sitting Bull and Crazy Horse at their fast-growing camp. Thousands strong, the group eventually settled on banks of the Little Bighorn River.

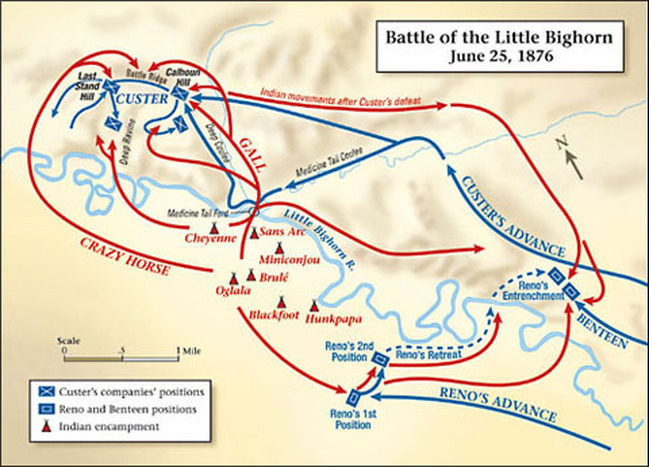

On June 22, General Terry decided to detach Custer and his 7th Cavalry to make a wide flanking march and approach the Indians from the east and south. Custer was to act as the hammer, and prevent the Lakota and their Cheyenne and Arapaho allies from slipping away and scattering, a common fear expressed by government and military authorities. General Terry and Colonel Gibbon, with infantry and cavalry, would approach from the north to act as a blocking force or anvil in support of Custer's far ranging movements toward the headwaters of the Tongue and Little Bighorn Rivers. The Indians, who were thought to be camped somewhere along the Little Bighorn River, "would be so completely enclosed as to make their escape virtually impossible."

June 10 1876 General Terry dispatched Reno and six companies of the 7th Cavalry to determine if there were any Indians on the Powder or Tongue rivers. If he found nothing significant he was to rejoin the Dakota column on the 19th. which (contrary to orders) would also scout the lower reaches of Rosebud Creek.

Major Reno discovered evidence of the largest Indian village anyone in the US Army had ever seen on the the Rosebud River. His scout reported sign these Indians were moving west to the Bighorn valley.

A Gatling gun and crew under 2nd Lt. Frank Kinzie accompanied Reno’s column. Reno’s scouting column passed over “very rough ground,” in the words of one soldier on the recon , an obstacle that required Kinzie’s gun crew to unhitch the horses, unlimber the Gatling and manhandle the piece across ravines. Kinzie and his gun crew, through great effort and a lot of ingenuity, confirmed Reno’s belief the guns could follow the cavalry through difficult terrain.

June 16, 1876 Lt Col George Armstrong Custer was kicked in the head by his favorite horse the thoroughbred, Victory. Custer died mediately. Custer had dismounted to clear what he thought was a rock from Victory’s left hind hoof. It turned out to be a jagged piece of buffalo horn jammed into the extremely sensitive laminae. When Custer touched it it caused great pain to Victory an the horse kicked out in reflex reaction.

Terry sent out a galloper to find Major Reno and inform him he was now “Acting” commanding officer of the 7th. Terry knew Reno had proven himself as a regimental CO during several long absences of Custer and refused to appoint anyone else to command the 7th until after this campaign was completed.

The intelligence gathered by Reno influenced Terry’s decision to send The 7th “in pursuit” of the hostiles.

June 16, 1876 Lakota and Cheyenne move into the Little Bighorn valley

June 17, 1876 The Battle of the Rosebud, took place during the Campaign of 1876. Brigadier General George Crook, along with his Crow and Shoshone scouts, had come north from Wyoming with approximately 1000 troops looking for the Sioux and Northern Cheyenne villages of Chief Sitting Bull. On the morning of June 17, near the headwaters of Rosebud Creek, Crook was unprepared for the organized attack of an equal or even greater number of warriors lead by Sioux Chief Crazy Horse and Cheyenne Chiefs Two Moon, Young Two Moon and Spotted Wolf. The presence of thousands of warriors and soldiers on the rolling hills of Southeastern Montana made the eight-hour engagement one of the largest battles of the Indian wars. This battle was also exceptionally significant because the Native Americans fought as an army with great intensity to defend their traditional land. Crook was stopped in his advance and the Native Americans were emboldened by the success.

Eight days later, because Crook's troops were withdrawn from the war zone to resupply, they were not available to support the 7th cavalry.

June 22 1876 Terry’s column with the 7th Cavalry ahead, left the Yellowstone River. This was part of an already failed pincer's movement against the Lakota and Cheyenne village.

June 24, Major Reno established a night camp twenty-five miles east of where the fateful battle would take place on June 25-26. The Crow and Arikara scouts were sent ahead, seeking actionable intelligence about the Lakota and Cheyenne. The returning scouts reported that the trail indicated the village turned west toward the Little Bighorn River and was encamped close by. Reno ordered a night march that followed the route that the village took as it crossed to the Little Bighorn River valley.

The 7th, was now commanded by Major Marcus Reno with Captain Myles Keogh as his XO.

Myles Walter Keogh was an Irish soldier. He served in the armies of the Papal States during the war for Italian unification in 1860, and was recruited into the Union Army during the American Civil War, serving as a cavalry officer, particularly under Brig. Gen. John Buford during the Gettysburg Campaign and the three-day Battle of Gettysburg. After the war, Keogh remained in the regular United States Army as commander of I Troop of the 7th Cavalry Regiment under George Armstrong Custer during the Indian Wars. He was not the senior Captain of the 7th but he was highly respected in the officer’s mess.

Although there was some grumbling, the army being what it is, all agreed Major Reno had the right to select his acting XO and most thought Keogh was the best man for the job.

Unlike Custer, Both Reno and Keogh considered the mobility problems of the Gatling’s outweighed by their fire power. Low found them very supportive in his efforts to attain good trace horses and allow live fire training of the gunners. On Reno’s part the size of the Lakota village he had scouted convinced him the 7th and Terry’s entire column was greatly outnumbered. He believed both the Spencers and these new fangle “Machine Guns” would make the difference between life and death IF the Lakota war chiefs managed to get their braves to attack in mass. When he thought about the way the Lakota and the rest of the Plain’s Indians had been treated by the Indian bureau under Grant he was more than half convinced this administration had already done the convincing for the War Chiefs.

June 25, 1876 Morning found the Lakota camp ripe with rumors about soldiers on the other side of the Wolf Mountains, 15 miles to the east, yet few people paid any attention. In the words of Low Dog, an Oglala Lakota: "I did not think anyone would come and attack us so strong as we were."

June 25, 1876 the 7’s scouts located the village of Lakota and Cheyenne, estimated at over 8,000 individuals, with 1,500-2,500 warriors. Lieutenant Edward Godfrey recalled Ree scout Bloody Knife reporting, “We’ll find enough Sioux to keep us fighting for two or three days.” Lieutenant Charles Varnum overheard the 7th’s chief scout, the mixed-blood Mitch Boyer, state to the Co of the 7th “If you don’t find more Indians in that valley than you ever saw before, you can hang me.” Co of the 7th replied, “Well, a lot of good that would do me.”

Early in the morning the 7th Cavalry Regiment was positioned near the Wolf Mountains, about twelve miles distant from the Lakota/Cheyenne encampment along the Little Bighorn River. The 7th’s scouts reported the regiment's presence had been detected by Lakota or Cheyenne warriors. The 7th’s CO, judging the element of surprise to have been lost, feared the inhabitants would attack or scatter into the rugged landscape, causing the failure of the Army's campaign.

Reno sent back a galloper to warn Terry of what was going on and that he intended an immediate advance to engage the village and its warrior force.

At first light, while his troopers were finishing up an early breakfast and preparing for the day’s march, reveille had sounded at 0500, Reno instructed Major Joel H. Elliott to send one troop from his Squadron (battalion) under his best Captain to provide an officer’s assessment and amplify the scout’s report. Elliott chose D Troop under Capt. Thomas Weir, 2nd Lt. Winfield Edgerly including Trumpeter and galloper John Martin , (Giovanni Martini). He was ordered to get the information and then return to the column and only fight if the “Hostiles” blocked his scout or return to the column. He was not to become “decisively engaged”.

Major Reno also ordered H Troop Capt. Frederick Benteen, 1st Lt. Francis Gibsonwith to determine if more Indian encampments extended to the south along the Little Bighorn River. He was not to fight any more than necessary to get the information back to Reno. Finding none, Benteen turned back north, to rejoin Reno with his information.

Major Reno sent a galloper, Sergeant Daniel Kanipe, to Lieutenant Edward Mathey commanding the pack train. He was to send Lt Low’s 3 gun detachment with all their ammo limbers to his position mediately. at their very best pace. Fortunately the gatling gun detachment had adopted a horse artillery organization (everyone rode a limber or a horse) and the 24 enlisted men of the 20th Infantry were composed of men who could ride well enough to keep up with the guns and limbers. Troop B, Mathey, and the rest of his pack train and Gun #3 and it’s ammunition limbers now pulled by 6 mules teams and 8 infantry gunners led by their gun chief, sergeant Beaufort, was to follow along at their best pace.

Mathey was in charge of the 175-mule pack train with Captain Thomas McDougall and his Company B escorting the train. The pack train contingent had been enlarged by pulling a few men from each of the other eleven companies; approximately 130 soldiers and civilian packers were with the pack train now. Every man was armed, most of the civilians with war surplus Henry Caliber .44 rim fire lever action Breech-loading rifles with a 15-round tubular magazine +1 round in the chamber rifles. The “gunners” with Colt revolving pistols.

As captain Weir’s, troop approached the village, hundreds of warriors responded to meet him. Weir called a halt, had his men dismount and form into a skirmish line. After a short time the skirmish line was flanked and he fell back to the woods along the river.

For a time, Weir 's troop, due to the fire power of their Spencers, held out in the woods as the Indian warriors surrounded the soldiers. When the Lakota. and Cheyennes fighting him began to infiltrate the woods, Weir decided his defensive position was untenable. At that time, Arikara scout Bloody Knife was shot in the head while Weir tried to communicate with him, covering Weir with brain matter and blood, blinding and stunning him. It was his trumpeter and galloper John Martin who used his canteen to wash the blood, bone chips and brain out of his Major’s eyes. With sight restored Weir was snapped back into the present, quickly ordered his troop mounted and led them in a headlong charge through the Lakota’s blocking force. His immediate objective was the bluffs across the river.

He left an understrength platoon in the woods under 2nd Lt. Winfield Edgerly as a rear guard. They were to hold mounted long enough for the rest of the troop to form line for a mounted charge and and then closely follow through the gap . Once through, Weir deployed his men into another Spencer armed skirmish line and covered the rear guard’s escape with a high volume of fire only a repeater could deliver. The entire troop then raced for a much better defensive position. 2nd Lt. Winfield Edgerly, five men of his rear guard and twelve other troopers and Non Coms were dead by the time the rest reached bluffs. Troop D was now down to 42 effective no one of which were wounded but capable of riding and fighting, for now.

On his way North to Reno Captain Benteen encountered Captain Weir's depleted command. Weir having made Captain three months earlier than Benteen ordered him to stay with his force. In response to the firing heard down river, Benteen urged Weir to respond to the sound of the guns, Reno’s force was being engaged by the Lakota scouts. Captain Weir decided to take his combined force of 93 North to unite the entire 7th cavalry under it’s commander Major Reno. This meant once again cutting through hundreds of warriors toward Reno's original position. Unknown to Weir or Benteen the hostiles confronting them had been reduced considerably by many going to respond to Reno’s threat further down river.

It was now clear to Captains Weir, Benteen and most of their non-coms that here at what the Lakota called the Greasy Grass, was concentrated the combined forces of the Lakota Sioux, Northern Cheyenne, and Arapaho tribes. The hostiles had finally settled their in terminal feuds to deal the White Eyes a killing blow before their tide drowned the entire great planes people. Here at a the Little Bighorn River on the Crow Indian Reservation in southeastern Montana Territory the 7th Cavalry Regiment of the United States Army was vastly outnumbered. Their duty was to rejoin Reno as soon as possible, give him the very, very bad news he was hopelessly outnumbered.

One thing Major Reno had learned under Custer was the danger of splitting his command in the face of superior enemy forces. Benteen did not have Custer’s luck, which was all that had saved the 7th on more than one occasions from dividing his command. The troops under his direct control sent out pickets to scout the immediate area and he held the rest dismounted but ready to swing into the saddle at a moments notice, if need be. The ground was such that he had soon lost sight of both scouting columns. The landscape is both gentle and very rugged. The upland to the east of the Little Bighorn Valley is highly dissected by a complex drainage system, consisting of ravines, coulees, and ridges. Elevations from the valley floor to the upland change as much as 340 feet. The slope in parts of the upland is greater than 10 degrees, and in rugged areas of the bluffs and along some ravines and other erosional features in excess of 30 degrees. The Little Bighorn Valley itself is a gentle northward sloping plain, with the Little Bighorn River flowing to the east side of the valley adjacent to the upland.

At 0830 Sergeant Daniel Kanipe led Lt Low and his 2 gun detachment with all their ammo limbers into camp. Low had pushed his gun teams hard but he had stripped No. 3 gun team of it’s horses as a fresh supply of replacements if the guns had to go into action before their teams were rested.

Lt Low reported to Major Reno as soon as he spotted him and reported Mathey and the rest of the pack train was to follow along at their best pace and should be up by noon. He also reported a picked column of 25 of the strongest mules packed light with just ammunition had been sent along ahead and should reach you by ten or so.

At 0950 a dozen of Captain Thomas McDougall’s B troop, under command of First Sergeant Polgardner came into camp with the 25 mules of the advanced pack train. Reno’s plan to concentrate his force before engaging the Hostiles was moving slower than he would have liked but he was sure it was the 7ths best chance to carry out it’s orders and survive to fight another day. Much would depend on the Gatling's and Spencers along with the steadiness of his men in today’s battle. He had more faith in his men than in his guns.

About 1000 2nd Lt. Charles Varnum, Reno’s Chief of Scouts, reported that one of his Crow scouts “Goes Ahead”, on the watch for Weir’s return could hear intermittent gun fire when the wind was blowing from Troop D’s direction. Reno ordered “Boots and saddles” and led the 7th with pickets ahead and on both flanks northward along the bluffs toward the broad drainage known as Medicine Tail Coulee, a natural route leading down to the river and the village.

Reno ordered C troop’s 2nd Lt. Henry Moore Harrington and an understrength platoon of 12 men to wait and direct the rest of the pack train and it’s escort to follow. He confided in Harrington his plans. Since Captain Thomas McDougall of B troop was senior to both Harringtion and Lieutenant Edward Mathey commanding the pack train, he was to make it clear Reno wanted those pack mules, their ammunition and supplies to close with the main force as soon as possible. He was also to divulge all he knew of my intensions to McDougall . If for any reason, most likely a large Lakota war party, the pack train was unable to come up; Captain McDougall was to find good defensible ground and build his defense using the remaining gatling gun as the lynch pin and send at least three veteran galopers, using different routes, to inform Reno of the situation.

About 1100 As it happened Captain McDougall’s command was first hit by a band of 300 Northern Cheyenne and Arapahos under the Cheyenne war chief Two Moons. They had manged to get behind Reno and were suppose to wait for the rest of the Indian force to hit the 7th from head on and on their flanks to close the trap. Instead the sight of that large pack train drove the young braves into a headlong attack hoping for an easy kill and a lot of booty.

McDougall, sized up the situation quickly and ordered B troop to form a skirmish line between the pack train and the attacking Indians. Fortunately Two Moons ha dlost control and his young warriors hit the skirmish line piecemeal with the better mounted in the lead. It was here the Spencers began to prove Reno correct. The men of B troop’s fire killed over two dozen braves and their horses in a matter of ten minutes. Two Moons beside himself with rage tried to head off his warriors only to be hit by Sergeant John Ryan, detached from M troop for pack train duty, using a .45-caliber, 15-pound Sharps telescopic rifle, specially made for him. He was with the pack train retreating up hill to their defensive position. Seeing the shot Lt Mathey ordered him to “Pick off every red skin bastard that looks like a leader.” By the end of the day Ryan had killed and mortally wounded over a score and a half of brave men.

Once on the military crest of the hill, with the damn gatling positioned on the high point in the center of the circular position, Mathey ordered the mules shot as brest works. They had no time to dig in and nothing else for cover and that included the gun team and limerr teams. He thought, if I live I’ll be paying for those damn mules for the rest of my life and laughed like an idiot. He caught himself when he saw the look on Harrington face.

Meanwhile McDougall’s skirmish line was being driven up hill and bent back upon it’s self as it was being flanked. He waited to decimate the next group of braves and had his bugle sound boots and saddles at which time the horse holders turned over their charges to their riders after helping the wounded into their saddles. Those too badly wounded to ride were given peace by the non coms. B troop went hell for leather about halfway up the hill and then reformed it’s thinned out skirmish line. The wounded were made their way to the pack train position.

Sergeant Beaufort’s Gun #3 teams of 8 infantry gunners had their weapon in position, loaded and ready to fire. He waited until the riding wounded were clear.

Lt Mathey seeing the gun ready ordered his bugler to sound recall until he ordered it stopped. McDougall, heard the call, saw the gun in battery and ordered boots and saddles again. This time he lead his troop to his left, which had only a few warriors at this moment, instead of up the hill. Once Beaufort saw B troop clear he order “Action Front, range three hundred yards” waited for the gunner to raise his arm, meaning he wss on target and ordered “Continuous fire until I tell you to stop O'Keef.” And “Tommy O’keef laid down a barrage that ripped into man and horse like a reaper through grain. O’Keef worked the gun left to right along the Indian advance and the .50 caliber rounds shredded them to pieces.

After expending an entire 400 round Broadwell Drum, with only 3 jams, Beaufort ordered them to reload but hold fire. O’Keef had to be be physically pulled from his gun because he was temporarily deaf. B troop, led by McDougall, jumped the dead mule breastworks and, all but the horse holders and wounded joined their comrade on the line. Of the 300 young braves, half were dead or dying. Many more of their ponies were just as bad off. Their leader Two Moons and anyone else wearing a particularly impressive war bonnet was also dead. Sergeant John Ryan was cleaning his rifle before it got anymore fowled by black powder. Water, which the pack train had in abundance, was passed out to the troops and civilians. The wounded were being taken care of by Surgeon George Lord. The medic had laudanum and morphine to ease pain, but not much else and a carbolic-acid solution was used to sterilize wounds. He performed two amputations while on the ridge, a lower leg of Private Mike Madden, and the upper half of the middle finger of Private John Phillips. Both men survived.

Acting Assistant Surgeon Henry Rinaldo Porter was with Benteen. He was shot in the fleshy part of his right thigh while in the wood. He bandaged himself, downed a dose of laudanum and continued to administer to the wounded.

Surgeons James DeWolf was with Reno’s main body of the Seventh and about to be engaged by over two thousand warriors. He would have an awful lot of work to do this day.

General Terry had sent Major Reno and the 7th Cavalry in pursuit of Sitting Bull’s trail, which had led into the Little Bighorn Valley. Terry’s plan was for Benteen to attack the Lakota and Cheyenne from the south, forcing them toward a smaller force that he intended to deploy farther upstream on the Little Bighorn River. This morning Benteen’s scouts had discovered the location of Sitting Bull’s village. Reno intended to move the 7th Cavalry to a position that would allow his force to attack the village at dawn the next day. When some stray Indian warriors sighted a few 7th Cavalrymen, Reno assumed that they would rush to warn their village, causing the residents to scatter.

June 25 about noon Reno, still missing Wier and Benteen’s Troops (about 120 troopers) and those with the pack train (about 100 troopers). He still had most of the 7th concentrated under his direct command (counting scouts and the gatling detachment about 500). He had his orders and so he chose to attack immediately, in an attempt to prevent Sitting Bull’s followers from escaping.

As the Battle of the Little Bighorn unfolded, Major Reno had his fears confirmed. The worst was Army intelligence had estimated Sitting Bull’s force at 800 fighting men; in fact, some 2,500 Sioux and Cheyenne warriors were facing the Seventh. The second was many of the braves were armed with repeating rifles. The third was Crazy Horse, leader of the Oglala band of Lakota, was just as formidable a tactician and leader as he had surmised. It also became obvious the Lakota and their allies had come here for war to the knife and the knife to the hilt. No quarter was asked or would be given by them this day.

As he advanced the concentrated Seventh to contact; a meeting engagement against great odds was in the offing. However the battle did open well when Wier and Benteen’s Troops, now about 80 strong broke though the still thin Lakota screen and joined with the Seventh. It was Weir’s report that finally confirmed the number of hostiles present at 2,000 to 2,500. A mobile fight was out of the question. He had to nail himself and his command to a good defensive position and allow his superior fire power to wear down the savages until he could go over to the offensive as they broke and ran. His Spencers and gatlings could do the job. He had plenty of ammunition and his was a veteran regiment, of combat hardened troops for the most part. His officers and senior Non Coms were all veterans of that horrible blood bath, the civil war, and they were still soldiers by their own choice. They knew their jobs and they would not break. He chose to make his stand on Calhoun Hill.

He detached C, L and I troops as a delaying force at a very favorable Medicine Tail ford bottle neck. Reno told the senior captain, that of I troop, this was not a suicide mission. He expected the three troops to hold their position until such time as he informed them to leave or until the hostiles made their position untenable . At that point they were to withdraw in good order to their next defendable ground and force the hostiles to do it all over again. Reno also made sure those troopers had plenty of ammunition.

Troops C, L and I at the cost of 43 dead or mortally wounded, include one captain and three lieutenants, bought the time needed to deploy a 360 degree defense perimeter with double skirmish lines of prone and kneeling troopers by troop. The horse holders and pack mules were stationed behind but in easy access to the battle line. The two Galings and their ammunition caissons were positioned in the center at the highest point on Calhon hill able to bring fire in any direction. He also held back a reserve of two companies, about 125 troopers to plug holes in the skirmish line.

Reno and the other veteran Indian fighters were surprised how few Lakota dismounted skirmishers were present. In the past afoot Indians, with their excellent war surplus, Henry rifles would use their unsurpassed hunting skills to get close enough to the skirmish line to kill off officers and non coms before the main body hit the troopers. Fortunately for the US Army Indians made horrible snipers, even the long term US Troopers with their paltry 20 rounds a year for target practice had a much high percentage of excellent marksmen and could often use the superior range of the Spencer to pick off Indian skirmishers IF they could see them. The Henry, carried by some of the Lakota, was a Caliber .44 rim fire, lever action Breech-loading rifles with a 15-round tubular magazine +1 round in the chamber Henry rifles. In the hands of a good marksmen could hit small to medium game at up to 200 yards. Against a man size target it had a maximum effective range of 200 yards in the hands of an average shooter, which most of the Lakota certainly were not.

Spencer repeating carbine, carried by the troopers had a rate of fire of 14-20 rounds per minute, at a muzzle velocity 931 to 1,033 feet per second. A trained marksman could hit targets as far as 800 yards away. Even a a first enlistment trooper could expect to strike a man sized target fairly often, say once in three shots at 350 yards and almost every time at 250 yards.

Before long, some Sioux criers came along behind the Lakota line, and began calling in the Sioux language to get ready and watch for the “suicide boys”. In many Native American traditions, those who reported news were called Camp Criers. Camp Criers would walk, run or ride from person to person or home to home until everyone was informed.

The Cheyenne and Lakota would revere men who belonged to the Dog Soldier warrior sect. The Dog Soldiers were known to wear a long sash which in times of greatest peril they would peg to the earth vowing to die where they stood in the defense of their colleagues. At Little Bighorn a group of Lakota and Cheyenne warriors who called themselves “The Suicide Boys” were to be, in the plans of the war chiefs, the decisive force in the fight. The desperate charge by these warriors who had pledged to die in the battle were to brake the greatly outnumbered and beleaguered 7th Cavalry.

From his position between the 7th and Lakota skirmishers Half-Sioux scout, Mitch Bouyer clearly heard and understood what he was being said. He raced to Reno’s side at this time and told him what he was hearing. He said “The Lakota were getting ready down below to charge together from the river, and when they come in, all the Indians up above should jump up for hand-to-hand fighting. That way the soldiers would not have a chance to shoot, but would be crowded from both sides.” The suicide boys would lead the way, they would turn to them and give those behind a chance to come in close. The criers called out those instructions twice. Most of the Cheyennes could not understand them, but the Sioux there told them what had been said.

Instead of coming on dismounted, taking advantage of the breaks in the ground to get close and use their repeaters to kill the soldiers while concealed or to circle the soldiers at long distance until they wore them down these braves conducted a series of mounted charges. Some were initially well coordinated and hit the entire perimeter of the Seventh’s skirmish line. Despite the havoc of the gatlings Reno had to throw in his reserve a number of times to plug holes in the skirmish line. As the afternoon wore on the Indian attacks, still in great force, became less coordinated and more hysterical.

At one point the warriors galloped up Calhoun hill with the intent of stampeding the horses held by the number four horse holders. The rest of the Suicide boys charged right in at the place where the soldiers were making their stand, and the others followed them.

The suicide boys never got to hand-to-hand fighting range as the spencers and gatlings were tearing the heart out of their attack.

At 1700, After the suicide boys had been massacred by spencer and gatling fire, it did not take long before Major Reno ordered boots and saddles and took the offensive. His objective was to drive them back toward their huge village killing them and their war ponies wholesale as they ran.

Sunset found the Seventh still killing. Reno called a halt for the night.

June 26, 1876 Gibbon and Terry acted as the anvil to the Seventh renewed attack. Eventually the Lakota were driven into the arms of the US army heavy infantry pincers, with their field artillery deployed to scour what was left of the Lakoda with canister and grape. That was the end of the campaign accept for the a little mopping up. Reno called it right. The Lakota were finished.

June 27, 1876 What were left of the Lakota and Cheyenne break camp and move off toward captivity.

july 4, 1876 American Centennial

July 6, 1876 Sherman and Sheridan receive confirmation of the campaign’s success

1876–1877 Army harasses off-reservation Indians throughout the fall and winter

May 6, 1877 Crazy Horse and his followers surrender

May 7, 1877 Sitting Bull and his followers cross into Canada

September 5, 1877 Crazy Horse killed