Post by miletus12 on Feb 23, 2022 2:49:39 GMT

Today is February 22, 2022. The date is Lincoln's birthday. There are two supreme political acts for which Lincoln is internationally famous. The first political act was to declare that the end of slavery was an ultimate aim of his administration's policy. Massively disguised as a "necessary war measure" undertaken as a military act, the true purpose of the Emancipation Proclamation (See text.), was to destroy the slavocracy as it existed and purge the United States of the pernicious effects this slavocracy's kleptocrats and pseudo-aristocracy had upon the meritocracy that Lincoln aimed to emplace in it's stead.

It should be remarked that the ever-incompetent George McClellan had managed to "not lose" at the Battle of Antietam and thus gave President Lincoln the "pretext" of a victory to publish his proclamation.

There is not a spot in a mythical hell hot enough to roast McClellan.

The actual military situation was such that Lincoln had to take "strategic steps".

The Emancipation Proclamation was designed to implement these strategic steps:

a. Neutralize the pro-Confederate elements in English and French ruling classes that sought to use the Confederacy's treasonous rebellion to weaken the United States as a competitor to their designs for geopolitical and economic dominance in the New World. Palmerston and Napoleon III clearly intended that the United States be destroyed. Once the Emanicipation Proclamation became understood among the populations of Great Britain and France as a war against slavery as well as a war to preserve the United States, American propaganda efforts to thwart foreign ruling governments' recognition of the rebellion as anything but a slavocracy class's attempt to retain human and thus would taint by association those "ruling European elites" with the same immorality and class interests as oppressors of "the common man", would be a lot easier. It also added the shotgun effect of recruitment among the failed 1848 revolutionaries in Europe in drawing to the Union, immigrants to America,k who would swell federal armies, and provide fresh manpower to man the Union's factories.

b. Take a third of the slavocracy's human potential out of active if coerced support to the Confederate cause. The Confederacy had 12 million human beings. About a third of them were slaves. Military manpower was potentially 1.5 million men at best. Reducing that manpower by a third was vital. As it stood, someone (Winfield Scott) who advised Lincoln, may have suggested that it would take killing one in four Confederate soldiers to bleed the slavocracy down to ruin. There is a lot of difference between murdering 400,000 men and 275,000 men. Lincoln was a cold-blooded practical man, who could understand Euclidean (military) logic. And it certainly happens, that he had at least one of the best military minds of the age as his personal advisor who could teach him the arithmetic of war if Lincoln was not versed in the details himself. *(See video) Lincoln was a GOOD self-taught strategist, who could have given the Elder Moltke a run for it and probably beaten that man.

c. Inform all "knowing" parties, that the conflict was now a "war to the knife". See b., if the details are still unclear. For the superficial understanders, such as that idiot, McClellan, the military outcome was now elevated to the pure economic and political environment. The slavocracy was to be destroyed and a capital / free labor system was to be established. The TRAGEDY was that Lincoln was not allowed to lay the postwar work needed to reshape American society. Instead: Andrew Johnson, a vain and petty revanchist bent on personal revenge, and the politically naive Ulysses Grant were left to mismanage Reconstruction and then the corrupt and incompetent James Garfield allowed "The Great Betrayal".

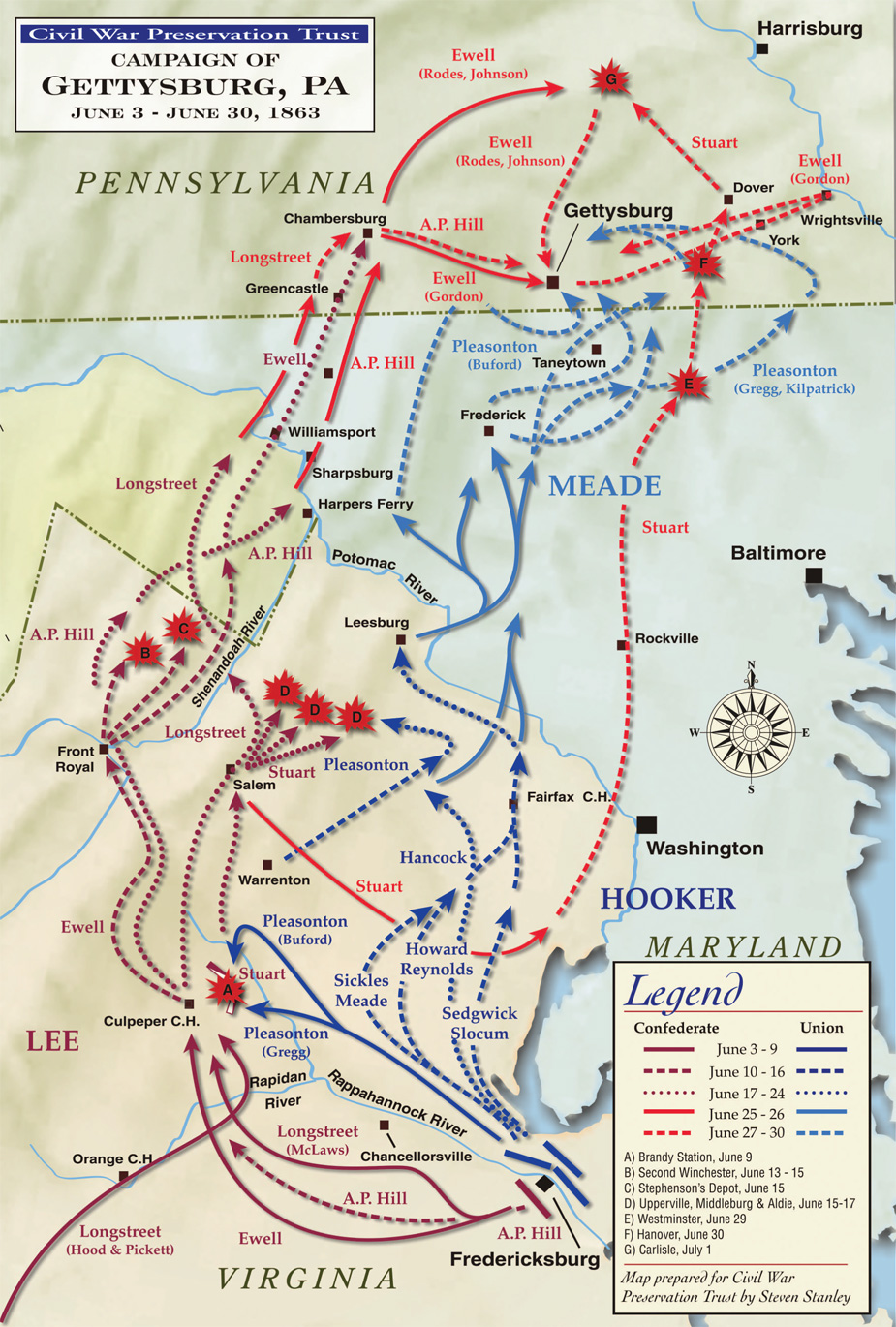

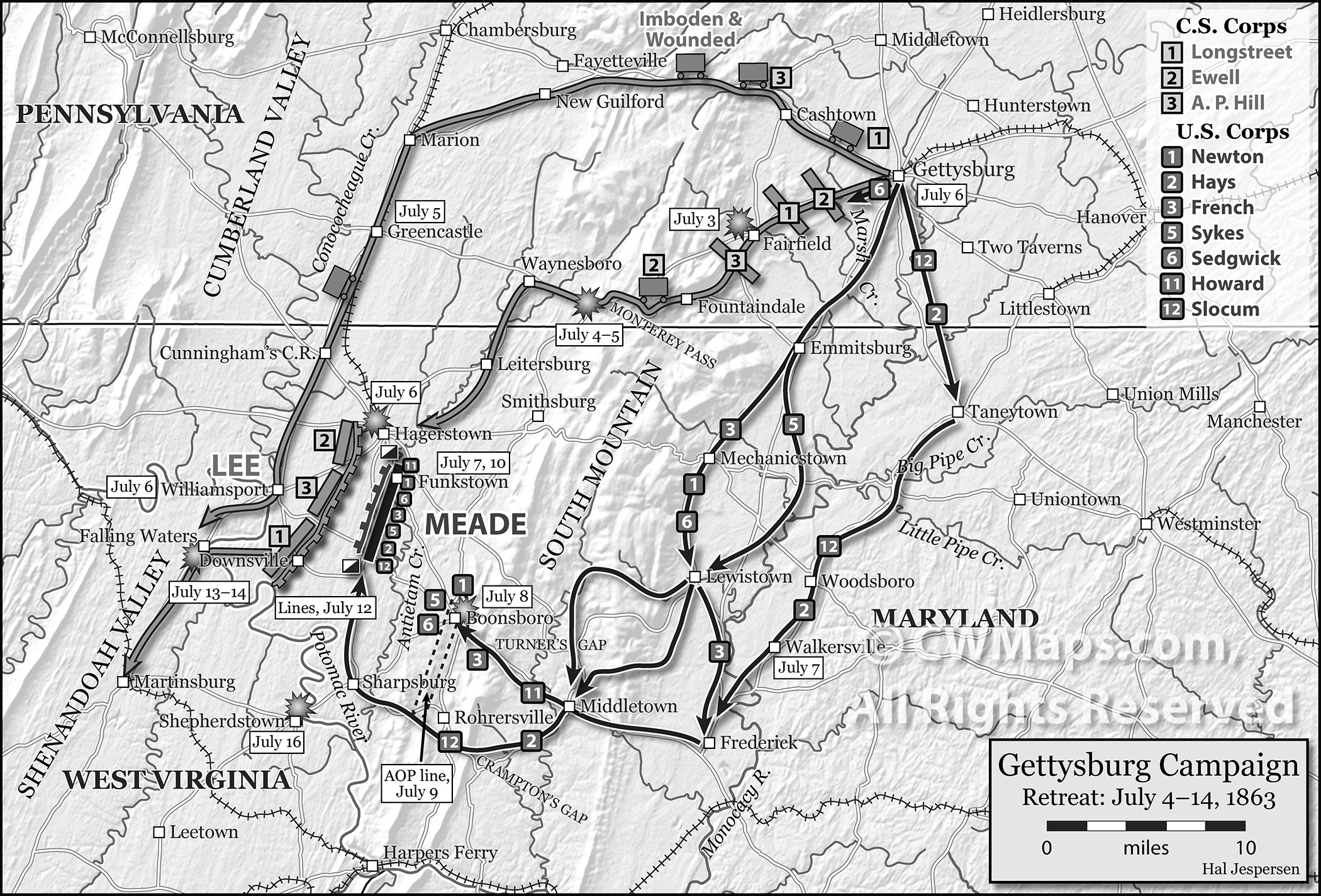

That gives some idea of the scope of vision and intent of Lincoln's first great political act. The inconclusive Battle of Gettysburg and the opportunity to lay down the Gettysburg Address as an "outcome" of Meade's botched victory will be tomorrow's installment.

Miletus.

The Emancipation Proclamation

January 1, 1863

A Transcription

By the President of the United States of America:

A Proclamation.

Whereas, on the twenty-second day of September, in the year of our Lord one thousand eight hundred and sixty-two, a proclamation was issued by the President of the United States, containing, among other things, the following, to wit:

"That on the first day of January, in the year of our Lord one thousand eight hundred and sixty-three, all persons held as slaves within any State or designated part of a State, the people whereof shall then be in rebellion against the United States, shall be then, thenceforward, and forever free; and the Executive

Government of the United States, including the military and naval authority thereof, will recognize and maintain the freedom of such persons, and will do no act or acts to repress such persons, or any of them, in any efforts they may make for their actual freedom.

"That the Executive will, on the first day of January aforesaid, by proclamation, designate the States and parts of States, if any, in which the people thereof, respectively, shall then be in rebellion against the United States; and the fact that any State, or the people thereof, shall on that day be, in good faith,

represented in the Congress of the United States by members chosen thereto at elections wherein a majority of the qualified voters of such State shall have participated, shall, in the absence of strong countervailing testimony, be deemed conclusive evidence that such State, and the people thereof, are not then in rebellion against the United States."

Now, therefore I, Abraham Lincoln, President of the United States, by virtue of the power in me vested as Commander-in-Chief, of the Army and Navy of the United States in time of actual armed rebellion against the authority and government of the United States, and as a fit and necessary war measure for

suppressing said rebellion, do, on this first day of January, in the year of our Lord one thousand eight hundred and sixty-three, and in accordance with my purpose so to do publicly proclaimed for the full period of one hundred days, from the day first above mentioned, order and designate as the States and

parts of States wherein the people thereof respectively, are this day in rebellion against the United States, the following, to wit:

Arkansas, Texas, Louisiana, (except the Parishes of St. Bernard, Plaquemines, Jefferson, St. John, St. Charles, St. James Ascension, Assumption, Terrebonne, Lafourche, St. Mary, St. Martin, and Orleans, including the City of New Orleans) Mississippi, Alabama, Florida, Georgia, South Carolina, North Carolina, and Virginia, (except the forty-eight counties designated as West Virginia, and also the counties of Berkley, Accomac, Northampton, Elizabeth City, York, Princess Ann, and Norfolk, including the cities of Norfolk and Portsmouth[)], and which excepted parts, are for the present, left precisely as if this proclamation were not issued.

And by virtue of the power, and for the purpose aforesaid, I do order and declare that all persons held as slaves within said designated States, and parts of States, are, and henceforward shall be free; and that the Executive government of the United States, including the military and naval authorities thereof, will recognize and maintain the freedom of said persons.

And I hereby enjoin upon the people so declared to be free to abstain from all violence, unless in necessary self-defence; and I recommend to them that, in all cases when allowed, they labor faithfully for reasonable wages.

And I further declare and make known, that such persons of suitable condition, will be received into the

armed service of the United States to garrison forts, positions, stations, and other places, and to man

vessels of all sorts in said service.

And upon this act, sincerely believed to be an act of justice, warranted by the Constitution, upon military necessity, I invoke the considerate judgment of mankind, and the gracious favor of Almighty God.

In witness whereof, I have hereunto set my hand and caused the seal of the United States to be affixed.

Done at the City of Washington, this first day of January, in the year of our Lord one thousand eight

hundred and sixty three, and of the Independence of the United States of America the eighty-seventh.

By the President: ABRAHAM LINCOLN

WILLIAM H. SEWARD, Secretary of State.

January 1, 1863

A Transcription

By the President of the United States of America:

A Proclamation.

Whereas, on the twenty-second day of September, in the year of our Lord one thousand eight hundred and sixty-two, a proclamation was issued by the President of the United States, containing, among other things, the following, to wit:

"That on the first day of January, in the year of our Lord one thousand eight hundred and sixty-three, all persons held as slaves within any State or designated part of a State, the people whereof shall then be in rebellion against the United States, shall be then, thenceforward, and forever free; and the Executive

Government of the United States, including the military and naval authority thereof, will recognize and maintain the freedom of such persons, and will do no act or acts to repress such persons, or any of them, in any efforts they may make for their actual freedom.

"That the Executive will, on the first day of January aforesaid, by proclamation, designate the States and parts of States, if any, in which the people thereof, respectively, shall then be in rebellion against the United States; and the fact that any State, or the people thereof, shall on that day be, in good faith,

represented in the Congress of the United States by members chosen thereto at elections wherein a majority of the qualified voters of such State shall have participated, shall, in the absence of strong countervailing testimony, be deemed conclusive evidence that such State, and the people thereof, are not then in rebellion against the United States."

Now, therefore I, Abraham Lincoln, President of the United States, by virtue of the power in me vested as Commander-in-Chief, of the Army and Navy of the United States in time of actual armed rebellion against the authority and government of the United States, and as a fit and necessary war measure for

suppressing said rebellion, do, on this first day of January, in the year of our Lord one thousand eight hundred and sixty-three, and in accordance with my purpose so to do publicly proclaimed for the full period of one hundred days, from the day first above mentioned, order and designate as the States and

parts of States wherein the people thereof respectively, are this day in rebellion against the United States, the following, to wit:

Arkansas, Texas, Louisiana, (except the Parishes of St. Bernard, Plaquemines, Jefferson, St. John, St. Charles, St. James Ascension, Assumption, Terrebonne, Lafourche, St. Mary, St. Martin, and Orleans, including the City of New Orleans) Mississippi, Alabama, Florida, Georgia, South Carolina, North Carolina, and Virginia, (except the forty-eight counties designated as West Virginia, and also the counties of Berkley, Accomac, Northampton, Elizabeth City, York, Princess Ann, and Norfolk, including the cities of Norfolk and Portsmouth[)], and which excepted parts, are for the present, left precisely as if this proclamation were not issued.

And by virtue of the power, and for the purpose aforesaid, I do order and declare that all persons held as slaves within said designated States, and parts of States, are, and henceforward shall be free; and that the Executive government of the United States, including the military and naval authorities thereof, will recognize and maintain the freedom of said persons.

And I hereby enjoin upon the people so declared to be free to abstain from all violence, unless in necessary self-defence; and I recommend to them that, in all cases when allowed, they labor faithfully for reasonable wages.

And I further declare and make known, that such persons of suitable condition, will be received into the

armed service of the United States to garrison forts, positions, stations, and other places, and to man

vessels of all sorts in said service.

And upon this act, sincerely believed to be an act of justice, warranted by the Constitution, upon military necessity, I invoke the considerate judgment of mankind, and the gracious favor of Almighty God.

In witness whereof, I have hereunto set my hand and caused the seal of the United States to be affixed.

Done at the City of Washington, this first day of January, in the year of our Lord one thousand eight

hundred and sixty three, and of the Independence of the United States of America the eighty-seventh.

By the President: ABRAHAM LINCOLN

WILLIAM H. SEWARD, Secretary of State.

It should be remarked that the ever-incompetent George McClellan had managed to "not lose" at the Battle of Antietam and thus gave President Lincoln the "pretext" of a victory to publish his proclamation.

CIVIL WAR | ARTICLE

McClellan at Antietam

Maryland Campaign

Photograph of McClellan discussing business in a tent

By Stephen Sears

In all his months as army commander, Major General George Brinton McClellan fought just one battle, Antietam, from start to finish. Antietam, then, must serve as the measure of his generalship. Colonel Ezra Carman, who survived that bloody field and later wrote the most detailed tactical study of the fighting there, had it right when he observed that on September 17, 1862, “more errors were committed by the Union commander than in any other battle of the war.”

General McClellan’s most grievous error was hugely overestimating Confederate numbers. This delusion dominated his military character. In August 1861, taking command of the Army of the Potomac, he began entirely on his own to over-count the enemy’s forces. Later he was abetted by Allan Pinkerton, his inept intelligence chief, but even Pinkerton could not keep pace with McClellan’s imagination. On the eve of Antietam, McClellan would tell Washington he faced a gigantic Rebel army “amounting to not less than 120,000 men,” outnumbering his own army “by at least twenty-five per cent.” So it was that George McClellan imagined three Rebel soldiers for every one he faced on the Antietam battlefield. Every decision he made that September 17 was dominated by his fear of counterattack by phantom Confederate battalions.

The testing of battle uncovered another McClellan failing – his management of his own generals. Of his six corps commanders, he displayed confidence in only two, Fitz John Porter and Joseph Hooker. He had termed 65-year-old Edwin Sumner “even a greater fool than I had supposed,” and regarded William Franklin as slow and lacking in energy. He had recently rebuked Ambrose Burnside for his tepid pursuit of the Rebels after the fighting at South Mountain. Joseph Mansfield, new to command, was an unknown quantity. McClellan called no council of his generals to explain his intentions, issued no plan of battle, and on September 17 conferred at length only with Fitz John Porter.

By taking up a defensive position west of Antietam Creek, General Robert E. Lee challenged McClellan to attack him. McClellan responded to the challenge with obsessive caution. He determined to strike Lee’s left, or northern, flank with at first just Joe Hooker’s First Corps. Crossing the Antietam behind Hooker and in support of him was Mansfield’s Twelfth Corps. The Second, Fifth, and Ninth Corps and the cavalry remained east of the Antietam. That stream would serve McClellan throughout the battle as a defensive moat against the counterattacks he anticipated. Franklin’s Sixth Corps was belatedly ordered up from Pleasant Valley, and only reached the field with the battle half over.

Having Hooker spearhead the attack, backed by Mansfield, was McClellan’s deliberate ploy to derail command influence by Ambrose Burnside and Edwin Sumner. On the march north from Washington, Burnside had commanded one wing of the army, comprising his Ninth Corps and Hooker’s First Corps. By peeling Hooker away and sending him to the opposite end of the battlefield, McClellan reduced Burnside’s authority by half, leaving that general sulking. Sumner had led the other wing of the army – his Second Corps and Mansfield’s Twelfth – on the march north. With Mansfield across the creek and slated to follow Hooker into battle, Sumner was left with only the Second Corps. Unlike Burnside, Sumner did not sulk at his demotion, but instead became more impatient to get into the fight.

McClellan’s initial design included a move against the Confederates’ other flank, to the south, by Burnside’s Ninth Corps. Either a diversion or a full-blooded attack – McClellan never made it clear which in dealing with Burnside – the assault was intended to prevent Lee from reinforcing against the Hooker-led main assault. However, since McClellan did not order Burnside to advance until the fighting elsewhere was three hours old, he was far too late to serve as a diversion. This was typical of McClellan’s orders that day – issued too late, or lacking in coordination, or reacting to events rather than directing them. Before long in that day of savage fighting, General McClellan lost control of the battle and fell captive to his delusions about the enemy he faced.

The morning struggle on the northern front – in the West Woods and the East Woods and the Cornfield and around the Dunker Church – proceeded in bursts from 6 a.m. onward and was unimaginably bloody. Hooker struck first with his First Corps. Rather than advancing to Hooker’s immediate support, Mansfield’s Twelfth Corps was posted too far back and brought up too late. The forces of Hooker and Stonewall Jackson shot each other to pieces without interruption.

It was not until 7:30 that the Twelfth Corps pushed past the shattered First to take up the fight. An early casualty was General Mansfield, struck in the chest with a mortal wound; General Alpheus Williams took over the command. Williams’s men were soon entangled in pockets of bitter fighting all across the northern battleground. Joe Hooker was wounded, depriving the Army of the Potomac of one of its best fighting generals at a critical moment. At nine o’clock Williams signaled McClellan: “Genl. Mansfield is dangerously wounded. Genl. Hooker wounded severely in foot. Genl. Sumner I hear is advancing. . . . Please give us all the aid you can.”

Sumner’s big Second Corps – its 15,200 men made it almost as large as the First and Twelfth Corps combined – was indeed finally advancing. But Sumner needed to cross the Antietam and march two miles to the scene of the fighting, so the Twelfth Corps, like the First, would make its fight alone. Even in unleashing Sumner, McClellan acted with exceeding caution. He permitted only two of Sumner’s three divisions to cross the Antietam. He held Israel Richardson’s division east of the creek until a division from the reserve came up to replace it. Only at nine o’clock would Richardson follow the rest of the Second Corps into action.

By then Sumner had marched straight into disaster. Furious at McClellan’s delays, he personally led John Sedgwick’s division onto the field – and into an ambush. Forty percent of Sedgwick’s men became casualties in hardly 15 minutes. To make matters worse, the trailing division could not keep pace with Sumner, lost direction, and struck the Rebel defenders of the Sunken Road, at the center of the battleground. Richardson’s division, released at last by McClellan, went to William French’s aid. This shifted the weight of the fighting to the Sunken Road.

During these early morning hours, as the First Corps, then the Twelfth, then the Second plunged separately into this fiery cauldron of a battle, McClellan held back Burnside’s Ninth Corps. Finally came word that the Sixth Corps, called up from Pleasant Valley, was approaching. This would replenish the defenses behind Antietam Creek, so McClellan released Burnside. The order, timed 9:10 a.m., read: “General Franklin’s command is within one mile and a half of here. General McClellan desires you to open your attack.”

While Burnside grappled with the problem of getting across the Antietam, the fighting at the Sunken Road abruptly turned in the Federals’ favor. Due to a mix-up of orders, the Confederate infantry abandoned the position, leaving a large gap in the center of Lee’s line. McClellan witnessed all this from Porter’s Fifth Corps headquarters, but by now he was drained of all aggressiveness. He ordered the troops at the Sunken Road to stand on the defensive.

William Franklin’s Sixth Corps was up now, and Franklin and his generals urged an assault against the depleted enemy defenses on the northern flank. McClellan rode to the scene, heard them out, then listened to a demoralized General Sumner insist that taking the offensive there would “risk a total defeat.” Bowing to his defeatist lieutenant, McClellan ordered the troops on the defensive here as well. One of Franklin’s generals, William F. Smith, termed it “the nail in McC’s coffin as a general.”

The last opportunity for a decisive victory fell to Ambrose Burnside. By one o’clock, after fumbling and false starts, Burnside seized a bridge across the Antietam and by three o’clock started a thrust toward Sharpsburg to turn Lee’s southern flank. Suddenly, seemingly out of nowhere, Confederate general A.P. Hill assailed the Ninth Corps’ open flank. Hill had marched his division 17 miles from Harper’s Ferry to reach the field at exactly the moment to stymie Burnside. Correspondent George Smalley was with the general commanding at Fifth Corps headquarters. McClellan, he wrote, “turns a half-questioning look on Fitz-John Porter, who stands by his side, and one may believe that the same thought is passing through the minds of both generals. ‘They are the only reserves of the army; they cannot be spared.’” Burnside, unsupported, retreated to his bridge.

This final Union setback was due as much to General McClellan as the rest of the day’s setbacks. Contrary to all the canons of generalship, he had not a single cavalry vedette guarding his army’s flanks. A.P. Hill’s assault came as a complete surprise.

Antietam must be judged the best chance to utterly defeat Robert E. Lee until that day two and a half years later at Appomattox. Against an enemy he outnumbered better than two to one, George McClellan devoted himself to not losing rather than winning. Nor would he dare to renew the battle the next day. The final measure of his self-delusion is his letter to his wife on September 18: “Those in whose judgment I rely,” he wrote, “tell me that I fought the battle splendidly & that it was a masterpiece of art.”

McClellan at Antietam

Maryland Campaign

Photograph of McClellan discussing business in a tent

By Stephen Sears

In all his months as army commander, Major General George Brinton McClellan fought just one battle, Antietam, from start to finish. Antietam, then, must serve as the measure of his generalship. Colonel Ezra Carman, who survived that bloody field and later wrote the most detailed tactical study of the fighting there, had it right when he observed that on September 17, 1862, “more errors were committed by the Union commander than in any other battle of the war.”

General McClellan’s most grievous error was hugely overestimating Confederate numbers. This delusion dominated his military character. In August 1861, taking command of the Army of the Potomac, he began entirely on his own to over-count the enemy’s forces. Later he was abetted by Allan Pinkerton, his inept intelligence chief, but even Pinkerton could not keep pace with McClellan’s imagination. On the eve of Antietam, McClellan would tell Washington he faced a gigantic Rebel army “amounting to not less than 120,000 men,” outnumbering his own army “by at least twenty-five per cent.” So it was that George McClellan imagined three Rebel soldiers for every one he faced on the Antietam battlefield. Every decision he made that September 17 was dominated by his fear of counterattack by phantom Confederate battalions.

The testing of battle uncovered another McClellan failing – his management of his own generals. Of his six corps commanders, he displayed confidence in only two, Fitz John Porter and Joseph Hooker. He had termed 65-year-old Edwin Sumner “even a greater fool than I had supposed,” and regarded William Franklin as slow and lacking in energy. He had recently rebuked Ambrose Burnside for his tepid pursuit of the Rebels after the fighting at South Mountain. Joseph Mansfield, new to command, was an unknown quantity. McClellan called no council of his generals to explain his intentions, issued no plan of battle, and on September 17 conferred at length only with Fitz John Porter.

By taking up a defensive position west of Antietam Creek, General Robert E. Lee challenged McClellan to attack him. McClellan responded to the challenge with obsessive caution. He determined to strike Lee’s left, or northern, flank with at first just Joe Hooker’s First Corps. Crossing the Antietam behind Hooker and in support of him was Mansfield’s Twelfth Corps. The Second, Fifth, and Ninth Corps and the cavalry remained east of the Antietam. That stream would serve McClellan throughout the battle as a defensive moat against the counterattacks he anticipated. Franklin’s Sixth Corps was belatedly ordered up from Pleasant Valley, and only reached the field with the battle half over.

Having Hooker spearhead the attack, backed by Mansfield, was McClellan’s deliberate ploy to derail command influence by Ambrose Burnside and Edwin Sumner. On the march north from Washington, Burnside had commanded one wing of the army, comprising his Ninth Corps and Hooker’s First Corps. By peeling Hooker away and sending him to the opposite end of the battlefield, McClellan reduced Burnside’s authority by half, leaving that general sulking. Sumner had led the other wing of the army – his Second Corps and Mansfield’s Twelfth – on the march north. With Mansfield across the creek and slated to follow Hooker into battle, Sumner was left with only the Second Corps. Unlike Burnside, Sumner did not sulk at his demotion, but instead became more impatient to get into the fight.

McClellan’s initial design included a move against the Confederates’ other flank, to the south, by Burnside’s Ninth Corps. Either a diversion or a full-blooded attack – McClellan never made it clear which in dealing with Burnside – the assault was intended to prevent Lee from reinforcing against the Hooker-led main assault. However, since McClellan did not order Burnside to advance until the fighting elsewhere was three hours old, he was far too late to serve as a diversion. This was typical of McClellan’s orders that day – issued too late, or lacking in coordination, or reacting to events rather than directing them. Before long in that day of savage fighting, General McClellan lost control of the battle and fell captive to his delusions about the enemy he faced.

The morning struggle on the northern front – in the West Woods and the East Woods and the Cornfield and around the Dunker Church – proceeded in bursts from 6 a.m. onward and was unimaginably bloody. Hooker struck first with his First Corps. Rather than advancing to Hooker’s immediate support, Mansfield’s Twelfth Corps was posted too far back and brought up too late. The forces of Hooker and Stonewall Jackson shot each other to pieces without interruption.

It was not until 7:30 that the Twelfth Corps pushed past the shattered First to take up the fight. An early casualty was General Mansfield, struck in the chest with a mortal wound; General Alpheus Williams took over the command. Williams’s men were soon entangled in pockets of bitter fighting all across the northern battleground. Joe Hooker was wounded, depriving the Army of the Potomac of one of its best fighting generals at a critical moment. At nine o’clock Williams signaled McClellan: “Genl. Mansfield is dangerously wounded. Genl. Hooker wounded severely in foot. Genl. Sumner I hear is advancing. . . . Please give us all the aid you can.”

Sumner’s big Second Corps – its 15,200 men made it almost as large as the First and Twelfth Corps combined – was indeed finally advancing. But Sumner needed to cross the Antietam and march two miles to the scene of the fighting, so the Twelfth Corps, like the First, would make its fight alone. Even in unleashing Sumner, McClellan acted with exceeding caution. He permitted only two of Sumner’s three divisions to cross the Antietam. He held Israel Richardson’s division east of the creek until a division from the reserve came up to replace it. Only at nine o’clock would Richardson follow the rest of the Second Corps into action.

By then Sumner had marched straight into disaster. Furious at McClellan’s delays, he personally led John Sedgwick’s division onto the field – and into an ambush. Forty percent of Sedgwick’s men became casualties in hardly 15 minutes. To make matters worse, the trailing division could not keep pace with Sumner, lost direction, and struck the Rebel defenders of the Sunken Road, at the center of the battleground. Richardson’s division, released at last by McClellan, went to William French’s aid. This shifted the weight of the fighting to the Sunken Road.

During these early morning hours, as the First Corps, then the Twelfth, then the Second plunged separately into this fiery cauldron of a battle, McClellan held back Burnside’s Ninth Corps. Finally came word that the Sixth Corps, called up from Pleasant Valley, was approaching. This would replenish the defenses behind Antietam Creek, so McClellan released Burnside. The order, timed 9:10 a.m., read: “General Franklin’s command is within one mile and a half of here. General McClellan desires you to open your attack.”

While Burnside grappled with the problem of getting across the Antietam, the fighting at the Sunken Road abruptly turned in the Federals’ favor. Due to a mix-up of orders, the Confederate infantry abandoned the position, leaving a large gap in the center of Lee’s line. McClellan witnessed all this from Porter’s Fifth Corps headquarters, but by now he was drained of all aggressiveness. He ordered the troops at the Sunken Road to stand on the defensive.

William Franklin’s Sixth Corps was up now, and Franklin and his generals urged an assault against the depleted enemy defenses on the northern flank. McClellan rode to the scene, heard them out, then listened to a demoralized General Sumner insist that taking the offensive there would “risk a total defeat.” Bowing to his defeatist lieutenant, McClellan ordered the troops on the defensive here as well. One of Franklin’s generals, William F. Smith, termed it “the nail in McC’s coffin as a general.”

The last opportunity for a decisive victory fell to Ambrose Burnside. By one o’clock, after fumbling and false starts, Burnside seized a bridge across the Antietam and by three o’clock started a thrust toward Sharpsburg to turn Lee’s southern flank. Suddenly, seemingly out of nowhere, Confederate general A.P. Hill assailed the Ninth Corps’ open flank. Hill had marched his division 17 miles from Harper’s Ferry to reach the field at exactly the moment to stymie Burnside. Correspondent George Smalley was with the general commanding at Fifth Corps headquarters. McClellan, he wrote, “turns a half-questioning look on Fitz-John Porter, who stands by his side, and one may believe that the same thought is passing through the minds of both generals. ‘They are the only reserves of the army; they cannot be spared.’” Burnside, unsupported, retreated to his bridge.

This final Union setback was due as much to General McClellan as the rest of the day’s setbacks. Contrary to all the canons of generalship, he had not a single cavalry vedette guarding his army’s flanks. A.P. Hill’s assault came as a complete surprise.

Antietam must be judged the best chance to utterly defeat Robert E. Lee until that day two and a half years later at Appomattox. Against an enemy he outnumbered better than two to one, George McClellan devoted himself to not losing rather than winning. Nor would he dare to renew the battle the next day. The final measure of his self-delusion is his letter to his wife on September 18: “Those in whose judgment I rely,” he wrote, “tell me that I fought the battle splendidly & that it was a masterpiece of art.”

There is not a spot in a mythical hell hot enough to roast McClellan.

The actual military situation was such that Lincoln had to take "strategic steps".

The Emancipation Proclamation was designed to implement these strategic steps:

a. Neutralize the pro-Confederate elements in English and French ruling classes that sought to use the Confederacy's treasonous rebellion to weaken the United States as a competitor to their designs for geopolitical and economic dominance in the New World. Palmerston and Napoleon III clearly intended that the United States be destroyed. Once the Emanicipation Proclamation became understood among the populations of Great Britain and France as a war against slavery as well as a war to preserve the United States, American propaganda efforts to thwart foreign ruling governments' recognition of the rebellion as anything but a slavocracy class's attempt to retain human and thus would taint by association those "ruling European elites" with the same immorality and class interests as oppressors of "the common man", would be a lot easier. It also added the shotgun effect of recruitment among the failed 1848 revolutionaries in Europe in drawing to the Union, immigrants to America,k who would swell federal armies, and provide fresh manpower to man the Union's factories.

b. Take a third of the slavocracy's human potential out of active if coerced support to the Confederate cause. The Confederacy had 12 million human beings. About a third of them were slaves. Military manpower was potentially 1.5 million men at best. Reducing that manpower by a third was vital. As it stood, someone (Winfield Scott) who advised Lincoln, may have suggested that it would take killing one in four Confederate soldiers to bleed the slavocracy down to ruin. There is a lot of difference between murdering 400,000 men and 275,000 men. Lincoln was a cold-blooded practical man, who could understand Euclidean (military) logic. And it certainly happens, that he had at least one of the best military minds of the age as his personal advisor who could teach him the arithmetic of war if Lincoln was not versed in the details himself. *(See video) Lincoln was a GOOD self-taught strategist, who could have given the Elder Moltke a run for it and probably beaten that man.

c. Inform all "knowing" parties, that the conflict was now a "war to the knife". See b., if the details are still unclear. For the superficial understanders, such as that idiot, McClellan, the military outcome was now elevated to the pure economic and political environment. The slavocracy was to be destroyed and a capital / free labor system was to be established. The TRAGEDY was that Lincoln was not allowed to lay the postwar work needed to reshape American society. Instead: Andrew Johnson, a vain and petty revanchist bent on personal revenge, and the politically naive Ulysses Grant were left to mismanage Reconstruction and then the corrupt and incompetent James Garfield allowed "The Great Betrayal".

That gives some idea of the scope of vision and intent of Lincoln's first great political act. The inconclusive Battle of Gettysburg and the opportunity to lay down the Gettysburg Address as an "outcome" of Meade's botched victory will be tomorrow's installment.

Miletus.