Post by melanie on Feb 22, 2022 15:57:25 GMT

Editor's note: This timeline is one of the most well done of the early internet alternate history pieces but it disappeared from the 'net some years ago with the end of Geocities. Here is what i managed to save.

The German Military Regime: from the Thirties onward

Doug Hoff

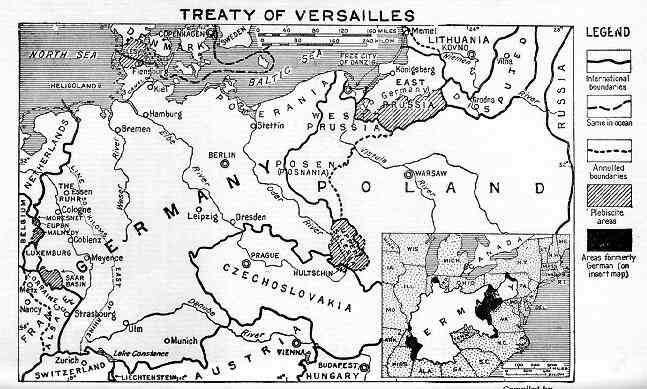

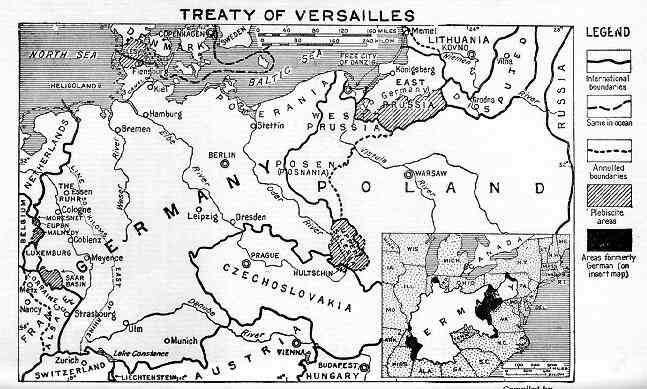

German Territorial Provisions of the Treaty of Versailles

Part the First: Prelude to a Coup

POINT OF DIVERGENCE:

1917: General Paul von Lettow-Vorbeck's (L-V) African forces are leading the British and South Africans on a merry chase throughout German and Portuguese East Africa, scoring a series of hit and run victories over the numerically-superior Allied forces. Cut off from the Fatherland, the German troopers are perpetually short of supplies and ammunition. L-V's efforts have made him a hero throughout the Reich, so the German government dispatches a long-range cargo airship loaded with fifteen tons of supplies. In our timeline, the ship, the L59, left Bulgaria and made it well into the Sudan before receiving an erroneous report that L-V's forces had been captured, so it turned around and headed back to German territory. The POD is this: the L59 never receives the message, continues its mission, and links up with L-V in German East Africa. Resupplied and reequipped, L-V pulls off even more upset triumphs over the Allies, causing his fame to rise even higher than it did in OTL. East Africa is not the decisive theatre of the war, however, and Germany still goes down to defeat as in OTL.

1919-1930: The Great War is over, and Germany is in chaos. L-V is back in the Fatherland, and plays an instrumental role is suppressing the Kapp putch against the Weimar republic. [In OTL, L-V aids the putch and resigns from the Army shortly thereafter] But, in this timeline, he is bouyed by his even greater successes and gratified by the support he received from the home front during the War, he decides to remain in the Army. Over the next ten years he is one leg of the troika that is instrumental in making the most of the Reichswehr, the diminutive army allowed Germany by the Treaty of Versailles, and secretly expanding its numbers and capabilities. L-V works with Generals Groener and Von Seeckt

Events progress as in OTL, with runaway inflation crippling the German economy in the early twenties, and the Nazi Party, like a vulture, prospering amongst the misery. Germany had, for the most part, recovered by 1929, when the bottom fell out of the tub: the Great Depression began.

The Republican government was paralyzed in the face of the crisis. The Chancellor, Heinrich Bruening, could not command a majority in the Reichstag for his fiscal measures. He resorted to calling upon President Hindenburg to rule by decree, as provided for in the German constitution. In the elections of 1930, the NSDAP wins an incredible number of votes, making it the second largest party in the Reichstag.

Concerns arise in the Army that the NSDAP is trying to infiltrate Germany's military institutions. These fears are borne out when two Lieutenants are arrested for distributing Nazi tracts in their barracks. The documents call on the Army not to resist an attempted Nazi putsch.

The government wants to try the two officers in the civil courts for treason. [POD: in OTL, they do]. L-V, in this timeline, prevails upon the government to allow the Army to discipline their own. At the court martial proceedings, Hitler testifies that the NSDAP has no intention of assuming power by any but constitutional means. L-V, who has read Mein Kampf, observes Hitler's testimony, and concludes that this "guttertrash," as he refers to Hitler privately, is a mortal danger to both the German Army and State. The two officers are convicted an sentenced, at L-V's insistence, to long prison terms.

L-V immediately consults with his two compatriots, von Seeckt and Groener, and persuades them that the Nazis must be stopped by any means necessary. The three Generals begin laying the groundwork for a coup d'etat. The Generals covertly contact many mid-level officers, securing their loyalty and directing them to report any unusual activity by the Nazis.

1932: The crisis arrives in the form of presidential elections. There are two leading candidates, Hindenburg and Hitler. Neither is acceptable to the Generals: Hitler, they are convinced, is more dangerous than ever and Hindenburg is lapsing in and out of senility. The Generals are appalled at the prospect of Hitler becoming president, and fear that the octogenarian Hindenburg would be in the grip of what they are referring to as the "Nazi-Communist Reichstag." The time has come to act.

Part the Second: The Coup d’etat

Midnight, March 10, 1932: The Generals spring into action. Von Seeckt and Groener order Reichswehr units in Berlin and other major German cities seize control of the post offices, radio stations, and government buildings. The Reichstag building is captured, and, in the morning, the deputies barred from entrance. Hindenburg is confined to his home. The Generals confront him in the early morning hours and ask his blessing for the coup. The old Fieldmarshall refuses to violate his oath to the Republic, but agrees to remain silent. Chancellor Bruening similarly refuses to acknowledge the coup and is placed under house arrest.

LV broadcasts a radio message announcing the coup to Germany. In his "Message to the German People," he announces that the Army carried out the coup to preserve "traditional German dignities and liberties" from destruction by revolutionary forces from the right and left. All political parties that do not affirm their loyalty to the new regime will be barred from the Reichstag.

Political reaction is swift: the parties of the Center and Left denounce the coup. The Socialists and Communists call for a general strike. A fierce debate ensues within the Nazi leadership: Gregor Strasser and Ernst Roem want to send the Brownshirts in to the streets and oppose the Army by force. Hitler temporizes, the orders the NSDAP Reichstag deputies to affirm their loyalty to the Generals. Better to be within the government than to be outlawed. He also hopes that, by acknowledging the coup, he can show the German public that the NSDAP is no threat to the Army.

Other right-wing parties also agree to work with the new regime and are seated in the Reichstag. The veterans private army, the Stahlhelm, places itself at the service of the Generals. It and the Army are instrumental in breaking up anti-coup demonstrations and strikes during the next weeks.

The Generals Consolidate Their Power:

When the "Generals’ Reichstag" convenes, it accepts Hindenburg’s and Bruening’s resignations (the latter coerced, the former out of fatigue). LV is appointed interim Chancellor and Von Seeckt as interim President. Groening remains in his office as Defense Minister. The terms of the President and Chancellor are extended indefinitely, and the President’s right to rule by decree is similarly confirmed without limit. Hitler seethes on the sidelines, but orders Nazi deputies to vote with the majority, fearing (rightly), that the Party will be outlawed and suppressed if it fails to cooperate.

The German populace reacts to the coup and subsequent events with relief: the Republic was paralyzed and lacked the confidence of the people, and the Army was the only institution they trusted. LV, a national hero, is viewed as a paragon of honesty and respectability. Sporadic street-fighting ensues as the Communists and Socialists push their efforts to overthrow the Generals. The Army and the Stahlhelm crush the rebellions; the SD stays at home. Within a month, calm has returned to Germany and the Army is firmly in control.

The split within the NSDAP does not heal: Roehm and Strasser now thoroughly distrust Hitler, believing that he is angling for a position in the military government, and is planning to sell them out to the conservatives. Hitler is, indeed, looking for an office within the Generals’ inner circle, hoping to sabotage from within their efforts to restore prosperity to Germany, then take the first available opportunity to seize power. The Generals rebuff Hitler’s overtures.

Locked out of power, with seemingly no way in, Hitler bides his time and considers his options.

Part the Third: Consolidation, Placation, and Conspiracy

Throughout early 1932, the Generals consult with and reassure the powers that be in Germany: big business, the Catholic political parties, the Junkers and the Church. The heads of the major industrial concerns back the troika with enthusiasm, especially after hearing about the regime’s economic plans. The large landowners are told that junta has no land reform agenda and will continue protectionist policies against agricultural imports. The "Vons" happily sign on.

The Catholic political parties continue to refuse to return to the Reichstag. The parties are in disarray, however, and cannot mount any serious opposition. The Catholic hierarchy backs the Generals, taking much of the popular enthusiasm out of their parties’ opposition. The Protestant churches’ fears are ameliorated after they hear that, unlike the NSDAP, the Generals plan to leave religious and moral issues to the religious authorities.

Groener reorganizes the police power in Germany: by decree, the state police forces are dissolved and replaced by a large paramilitary gendarme controlled by the Berlin government.

Von Papen, the Generals’ new foreign minister, makes the rounds in the European capitals, reassuring France and Britain that Germany has no designs "contrary to the interests of justice and peace in Europe." Meeting secretly with Molotov, Von Papen and the Soviet Commissar agree to continue Germany’s secret military cooperation with the USSR.

The only organized political forces in Germany that continue to stand against the regime are the NSDAP, the Social Democrats (backed by the powerful labor unions) and the Communists. The generals turn on the unions first.

May 1, 1932: on international labor day, the junta hammers the unions. With thousands of workers in the streets, Army units raid various union headquarters, seizing the buildings and the membership records. The government also confiscates the labor unions’ bank accounts, promising to hold them in trust for the "German workers" and out of the "grasping hands of the internationalist, communist-controlled union leadership." Labor leaders are arrested. The junta founds new "national" (i.e. government-controlled) unions, which work hand in glove with big business. The power of the once-powerful German labor organizations is broken. With their collapse, the Social Democrat and Socialist parties fold as effective organizations.

Only the NSDAP remains. The Party leadership is split: the breaking of labor has outraged Strasser and Roehm, who again demand to take the brownshirts into the streets against the Army. Hitler is in a quandary: out in the cold with the regime and lacking any alternatives. His grip on the party is slipping. Goering and Goebbels back Hitler, but their enthusiasm is waning during the months of inactivity.

Having baited the trap, L-V springs it. On October 15, he issues a decree banning all paramilitary organizations (excepting the Stahlhelm, which is deputized as an auxiliary to the police). At a meeting of the top Nazi leadership, Roehm and Strasser confront Hitler. They demand action. Hitler is alone; Goering and Goebbels avoid the meeting. The SD leadership have their way and plans for a Nazi putsch are in the making.

Part the Fourth: Caught Flat-Footed

On October 16, Roehm calls on the Brownshirts to assemble in Berlin, Nuremberg, and Munich on October 18 to protest the ban. The Generals cannot believe their luck, and begin assembling the Reichswehr, the Stahlhelm and the paramilitary police to attack and seize the SA when it assembles.

Roehm, however, is too clever by half, and on midnight the night of the seventeenth, he and hundreds of heavily armed Brownshirts invade the Reichstag, the Defense Ministry buildings, the Chancery and the Presidential palace. Groener is caught napping and is captured by the SA. With the help of his bodyguards, L-V shoots his way out of the Chancery and flees to the safety of the Potsdam garrison. Von Seeckt is killed in the battle for the Presidential palace.

Groener is held hostage as Strasser and his troops seize a radio station and broadcast a call to all SA units in the country to march on Berlin and battle the "reactionary forces who have subverted the army and oppressed the German workers." The next morning, tens of thousands of Brownshirts are seizing trains and trucks and making their way to Berlin. Some units, who had already arrived for the "protest" invade and take over the municipal buildings in Munich and Nuremberg. All over Germany, the SA is running riot, smashing Jewish homes and businesses and attacking the police, Army, and Stahlhelm units.

Roehm, now joined by Hitler, Goering and Goebbels, (belated converts when success seems near) proclaims the dissolution of the military government and the formation of a new cabinet, which will exercise legislative powers "until new elections can be held" at some unspecified date.

L-V, however, is telegraphing (the SA has not cut the lines) and radioing orders from Potsdam to Army and police units throughout the Reich. The police are to suppress the local SA insurgents, while all available Reichswehr units are to converge on Berlin.

Throughout October 18, the junta’s counterattack is in full sway, with the police and their Stahlhelm auxiliaries battling the Brownshirts in every major city in Germany. Machinegun and rifle fire blaze in streets. Hundreds are killed on both sides as governmental forces retake the central Munich police station and municipal buildings. The police attack in Nuremberg is ill-coordinated, and the rebels repulse the police from behind barricades. Government aircraft, the fruits of the secret cooperation with the Russians, strafe and in some cases bomb, trains carrying SA units to Berlin.

In Berlin, thirty thousand Brownshirts, under Strasser’s personal command, take up positions at key points throughout the city. Most are armed with rifles and a scattering of machineguns and mortars, either from the Nazis stockpile or from armories looted in the city. Thousands of others, however, wield nothing but pipes and "Goebbels cocktails."

At three a.m. in the morning on the nineteenth, the Army attacks. General Kurt von Schleicher commands the assault [point of AH irony: in OTL, he was killed by the SS during the "Night of the Long Knives"]. Dozens of armored cars (also developed in coordination with the Russians) spearhead the assault, followed by storm troopers armed with rifles, submachine guns and flamethrowers. Artillery is called in to reduce SA street barricades. Berliners hunker down in their cellars and await the outcome of the civil war raging in the streets above.

Part the Fifth: Denouement at Nuremberg

October 19-21: In Berlin, the Army fights its way towards the governmental complex, street by street and house by house. Spurred on by Strasser’s battlefield leadership, the SA puts up vigorous resistance, even though it is hopelessly outgunned by the Reichswehr. The Army’s tanks and armored cars, as well as superior fire discipline, tell the tale, and by nightfall on the twentieth, the government forces are closing in on the Reichstag buildings, as well as the Presidential palace and the Chancery.

Leading from the front, Strasser is killed in the fighting. In the Presidential palace, panic reigns: the Nazi conspirators know that they face the hangman’s noose if captured, and their hopes of defection by the younger Reichswehr officers have been dashed. Goebbels and Goering favor fleeing to Rome and forming a government in exile. Hitler, however, refuses to leave German soil. Personal relations among the Nazi leadership collapse, and they decide to split up to lessen the risk of the whole group being captured at once.

On the morning of October 21, Hitler flees east, and eventually makes his way to Danzig. Goebbels and Goering head south, making it eventually to Switzerland and then on to Fascist Italy. Roehm, refusing to give up hope, escapes Berlin in disguise, hoping to make his way to Nuremberg. He is spotted by an Army patrol outside the city and captured.

Abandoned and leaderless, SA resistance in Berlin collapses, and L-V enters the city, personally raising the German flag over the Presidential Palace while surrounded by cheering soldiers and civilians. Newsreel footage of this event is shown throughout the nation, and, on the twenty-first, once an operable radio station is found, L-V proclaims to the nation that the Army is once again in control of the capitol.

On October 22, the Brownshirts in Nuremberg, who had been successfully holding off the police and the Stahlhelm, learn that Strasser is dead and Roehm captured, surrender. In the parts of the city under SA control, corpses of Jews are found hanging from the lampposts, their homes and shops sacked and burned by the SA. Middle class Germany recoils in horror at the newsreel footage of the murdered civilians.

L-V, now in undisputed control of the government, forces Groener’s resignation ("on grounds of ill-health" due to injuries suffered at the hands of his Nazi captors), Von Schleicher replaces him as Defense Minister, and by a unanimous vote of the puppet Reichstag (voting in the ruins; a very dramatic scene) L-V assumes the Presidency as well as the Chancellorship.

Martial law is now further tightened. All major offenses are tried by military courts, and all Nazi publications are suspended indefinitely. The surviving SA members are forced to renounce their allegiance to the NSDAP, and membership in the Nazi party is declared to be an capital offense.

The funeral for von Seeckt is suitably elaborate for the fallen President, and Roehm’s show trial is spectacular. The Nazi menace is put on full display, in radio broadcasts, newspapers, and newsreels. L-V has the public fully behind him for his crackdown on what remains of the NSDAP.

Hitler is in hiding in Danzig, where the free city government promises L-V to extradite him if he can be found. Goebbels and Goering continue their farcical government in exile from Rome. Mussolini, in a display of fraternal good will to his fellow fascists, refuses multiple German deportation requests. Roehm is executed in December.

Heinrich Himmler, leader of the SS, takes overall command of the NSDAP, and begins laying the groundwork for a covert Nazi movement.

Part the Sixth: Quiet Times and a Modest Proposal

Firmly ensconced as head of state as well as head of government, Lettow-Vorbeck now starts to pay back the chits he had outstanding. To the big industrial concerns, he gives a wholesale repeal of the antitrust laws, and grants industry organizations the power to jointly set prices and wages. Strikes are effectively outlawed by decrees that only the "official" labor unions can call them and, as noted previously, these are effectively arms of government and big business. Public works projects are instituted, sopping up some of the unemployed labor, and both industry and the military clamber for rearmament, but L-V insists upon waiting for the international situation to improve.

During the Nazi putsch, L-V had moved troops into cities in the demilitarized Rhineland. L-V contacted French President Lebrun, and informed him that the troops were present for internal security purposes only. After the crisis passes, L-V again contacts Lebrun, and argues that the troops must remain in the Rhineland, lest it become a "hotbed of Nazi and Communist agitation." Renaud reluctantly agrees after L-V assures him that no tanks or heavy artillery will be moved into the area. L-V thus accomplishes two things: the British are furious at the French for not being consulted, and the Rhineland is remilitarized without fanfare and without crisis. The acknowledgement that Germany has a few "armored security vehicles," as they are referred to, does not unduly disturb the French or British, although they are exist in apparent violation of the Versailles Treaty.

In the international arena, Germany plays the role of model European citizen. L-V declares on a number of state occasions that his primary goal is recovery from the Depression and restoration of "law and order" to Germany. When pressed, he declines to promise the Powers that Germany is disinterested in restoring its pre-1918 borders, but suggests that he cannot give such assurances for domestic political reasons, "Should I make such a statement aloud," L-V tells Anthony Eden, "the Army would have me on the street in a fortnight." Privately, he approaches the French and British leadership and suggests common cooperation against "fascist and communist agitation and subversion."

Germany maintains its distance from fascist Italy. L-V frequently refers to Mussolini as "that strutting ape," and comments that he and his old African unit could be in Rome while the Italian army was still putting its boots on. German military cooperation continues with the Russians, although L-V is rapidly losing enthusiasm for the project. "Working with that atheist Georgian bank-robber, as L-V refers to Stalin, "demeans Germany and makes me feel dirty."

In May, 1933, L-V feels secure enough in his power to make a foreign trip. He travels to London, where he meets with Eden and discusses the overall European situation. He also meets with his old adversary from the African campaigns, Jan Smuts. L-V makes a very favorable impression on the British public, especially after his amiable and nostalgic reunion with Smuts. British hospitality also impresses L-V, and he leaves with very strong feelings towards England.

On May 16, Franklin Roosevelt proposes a general reduction in armaments, including a total ban on bombers and tanks. The next day, L-V addresses the Reichstag and announces that Germany accepts President Roosevelt’s proposal and is willing to join in any "general armament reduction regime."

Of all the world leaders, L-V notes, only he knows first-hand the "terrors" and "horrible waste of war."

"Germany is already effectively disarmed," L-V states, "and it would welcome equality with other states in abolishing the scourge of armed conflict forever." L-V’s comrades in the Reichswehr are horrified. Immediately after L-V’s speech, plans for another coup are in the making.

Part the Seventh: Told You So.

Throughout May and June of 1933, Lettow-Vorbeck stumps for disarmament. In the Saar, temporarily detached from the Reich and scheduled to have a referendum on its status in 1935, L-V states publicly that Germany will abide by the outcome of the vote and, that Germany "has no desire for one square inch of French soil, including Alsace-Lorraine." Since "Germany has no quarrel with France, France should not fear disarmament . . . unless France has some quarrel with Germany."

Von Papen visits Washington and meets with Roosevelt, who welcomes Germany’s "conversion to the cause of peace." The European powers are markedly less enthusiastic. Peace organizations in France and Britain stage rallies in favor of the treaty, but both governments consider ways to reject the agreement while appeasing public opinion.

On June 21, Japan formally rejects the disarmament proposal. This provides the French and British the excuse they need. The British state that they must "regretfully" decline the proposal. The next week the French also decline to discuss disarmament.

On June 30, L-V again addresses the Reichstag. He rues that "the hand that Germany extended to Europe has been refused."

"If Germany and the other powers cannot be equally disarmed," L-V states, "then Germany and Europe must be equally armed." Germany’s signature to the Versailles Treaty’s arms-limitation provisions is to be considered "withdrawn" from this day forward. "Germany will rearm, consistent with her dignity and position in Europe."

This is the big gamble. If the Western Powers act decisively, Germany, even with its secret arms programs, will be helpless.

Shortly after the speech, the German ambassador in London approaches the British government and proposes an agreement: Germany will unilaterally limit its navy to 35% the size of the Royal Navy. The British grasp this proposal, and within a week, the Anglo-German Naval Accord is signed. Abandoned by the British, the French protest German rearmament, but do not move.

Under the pretext of discussing the military buildup, L-V calls into his office the leadership of the General Staff, which was involved in the conspiracy against him: von Fritch, Blomberg, and Keitel. He confronts them with their "treasonous behavior" and demands an "explanation." The three generals confess their plot. In the old days, L-V says sternly, they would find a pistol in each of their desks, and no further discussion would be necessary. Magnanimously, and to the Generals’ astonishment, L-V pardons them, because, he says, they acted in what they thought was in the best interests of the Reich. The Generals pledge their "eternal loyalty" to L-V.

With both the government and the Army in his back pocket, L-V commits Germany to building up its military in full view of the world. With the renunciation of the Versailles "diktat," his standing soars ever higher with the German public.

Part the Eighth: Intermezzo

1933-35: Lettow-Vorbeck concentrates on two things: the buildup of the German Army and preempting any British and French sanctions for the buildup. He scrupulously adheres to the provisions of the Anglo-German Naval Accord. L-V’s concern is not with the Navy: "The Kaiser’s biggest mistake," he confides to von Fritch, "was attempting to challenge British naval supremacy. It alienated England, and when the day of decision came, meant nothing." Besides, the Army needs the money. No heavy (i.e. seagoing) submarines are laid down, but keels, engines and equipment are secretly stockpiled. He buys off the Navy with a couple of showpiece battleships and one aircraft carrier, the Tirpitz, which he christens himself in 1935.

German unemployment plummets as the buildup roars on. Tanks and guns roll of the Krupp assembly lines at a furious pace. The German Army Air Corps comes out of hiding, equipped with the latest fighters and bombers. Work begins, also, on the Western Wall, the series of fortifications near the border with France. In May of 1934, L-V takes a momentous step: he reinstitutes conscription. The French and British are strangely quiescent.

The Nazis, under Himmler’s leadership, but technically loyal to the "government in exile" in Rome, begin a terrorist campaign aimed at causing the regime to become intolerably oppressive, and thereby triggering a general uprising. Bombs detonate at police stations, governmental offices, and officer’s quarters. The regime institutes swift countermeasures, resulting in the arrests and incarceration (without warrant or trial) of hundreds of suspected Nazis. Infiltration of the Nazi underground is difficult because it is divided into cells, but information gathered seems to point to the movement receiving support from abroad.

In foreign policy, L-V continues to make a show of seeking disarmament, confident that none of the other great powers will take him up on his offer. He also issues feelers to the World War One Allies, seeking the return of Germany’s former colonies. All his initiatives are rebuffed. Nonetheless, he makes special efforts to cozy up to England, where he is a Conservative Party favorite for his strong anti-communist and anti-fascist stands and the naval treaty.

The European situation remains largely calm until late 1934, when Italian troops clash with Ethiopian forces at Ualval, beginning Mussolini’s conquest of one of the last independent parts of Africa. On January 7, 1935, the Laval government in France secretly agrees to let Italy take Ethiopia. By mid-February, the Italians’ offensive is in full swing.

Lettow-Vorbeck, seizing the opportunity to further improve relations with Great Britain, backs a League of Nations resolution condemning Italian aggression and proposing trade sanctions against the Italians. With German backing, the British close the Suez canal to Italian shipping. The logistical situation of the Italian forces becomes increasingly pinched.

In 1935, after a decisive plebiscite vote, the Saar rejoins Germany. Lettow-Vorbeck, who is from the area himself, addresses a huge rally after the election, promising that Germany is "on the road to greatness" and that the other nations of Europe need fear nothing from Germany, since a stable Reich is a peaceful Reich. After the Saar plebiscite, German communities in other territories lost after World War 1 begin organizing and agitating for similar treatment.

With military cooperation with the Soviets abruptly ended, relations between German and the USSR cool decisively. L-V’s public rhetoric grows decisively anti-Soviet. Germany’s relationship with Mussolini’s Italy are even colder; each Nazi terrorist attack generates a new German demand that the Nazi leadership be extradited, or at least expelled, from Italy. Mussolini steadfastly refuses, thus preserving his image as leadership of international fascism and a strongman capable of standing up to foreign "reactionary" powers.

Hitler continues to live a fugitive’s existence in Danzig, where he is hunted by an increasing numbers of German agents infiltrated into the free city.

Part the Ninth: Isolate and Neutralize

1935-1936: With the revelation of the Laval-Mussolini agreement on Ethiopia, the break between France and Britain is complete. The Royal Navy, reinforced by German vessels, stares down the Italian threat in the Mediterranean. The French participate in the League of Nations boycott of Italy, double-crossing Mussolini, but the effort is led by the Anglo-German "entente." In 1936, Chamberlain assumes the Prime Ministership. Their supply situation growing desperate, and the Ethiopians receiving additional supplies and munitions from the League powers, the Italian forces under Bagdolio retreat into Italian Somaliland. With the disgrace of defeat, Bagdolio is forced to resign, the scapegoat for the Duce’s failure. However, events arise that offer Mussolini an opportunity to salvage Italy’s prestige.

In July of 1936, the Spanish Moroccan garrison mutinies against the leftist Madrid government. The revolt, led by General Francisco Franco, begins the Spanish Civil War. Mussolini, seizing the opportunity to expand his influence, backs the rebels. After much heated domestic debate, France and Great Britain call for non-intervention and propose an international arms embargo. Stalin backs the Spanish government and rushes aid to the Republican forces.

Lettow-Vorbeck is torn: he wants to contain Bolshevism, but also desires to stay in good with the Western powers and despises Mussolini. He overrides the opinions of several of his top advisors and throws in with France and England in backing the arms embargo. Notwithstanding the efforts of what people in the know are calling The Big Three (Germany, the United Kingdom, and France), Franco’s forces and their Italian allies continue to push the Republicans back towards Madrid.

Towards the end of 1936, however, it is events in Eastern Europe that capture the attention of Europe. The German agents that have been hunting for Hitler have been moonlighting: the Free City of Danzig rises against its League government.

The German Military Regime: from the Thirties onward

Doug Hoff

German Territorial Provisions of the Treaty of Versailles

Part the First: Prelude to a Coup

POINT OF DIVERGENCE:

1917: General Paul von Lettow-Vorbeck's (L-V) African forces are leading the British and South Africans on a merry chase throughout German and Portuguese East Africa, scoring a series of hit and run victories over the numerically-superior Allied forces. Cut off from the Fatherland, the German troopers are perpetually short of supplies and ammunition. L-V's efforts have made him a hero throughout the Reich, so the German government dispatches a long-range cargo airship loaded with fifteen tons of supplies. In our timeline, the ship, the L59, left Bulgaria and made it well into the Sudan before receiving an erroneous report that L-V's forces had been captured, so it turned around and headed back to German territory. The POD is this: the L59 never receives the message, continues its mission, and links up with L-V in German East Africa. Resupplied and reequipped, L-V pulls off even more upset triumphs over the Allies, causing his fame to rise even higher than it did in OTL. East Africa is not the decisive theatre of the war, however, and Germany still goes down to defeat as in OTL.

1919-1930: The Great War is over, and Germany is in chaos. L-V is back in the Fatherland, and plays an instrumental role is suppressing the Kapp putch against the Weimar republic. [In OTL, L-V aids the putch and resigns from the Army shortly thereafter] But, in this timeline, he is bouyed by his even greater successes and gratified by the support he received from the home front during the War, he decides to remain in the Army. Over the next ten years he is one leg of the troika that is instrumental in making the most of the Reichswehr, the diminutive army allowed Germany by the Treaty of Versailles, and secretly expanding its numbers and capabilities. L-V works with Generals Groener and Von Seeckt

Events progress as in OTL, with runaway inflation crippling the German economy in the early twenties, and the Nazi Party, like a vulture, prospering amongst the misery. Germany had, for the most part, recovered by 1929, when the bottom fell out of the tub: the Great Depression began.

The Republican government was paralyzed in the face of the crisis. The Chancellor, Heinrich Bruening, could not command a majority in the Reichstag for his fiscal measures. He resorted to calling upon President Hindenburg to rule by decree, as provided for in the German constitution. In the elections of 1930, the NSDAP wins an incredible number of votes, making it the second largest party in the Reichstag.

Concerns arise in the Army that the NSDAP is trying to infiltrate Germany's military institutions. These fears are borne out when two Lieutenants are arrested for distributing Nazi tracts in their barracks. The documents call on the Army not to resist an attempted Nazi putsch.

The government wants to try the two officers in the civil courts for treason. [POD: in OTL, they do]. L-V, in this timeline, prevails upon the government to allow the Army to discipline their own. At the court martial proceedings, Hitler testifies that the NSDAP has no intention of assuming power by any but constitutional means. L-V, who has read Mein Kampf, observes Hitler's testimony, and concludes that this "guttertrash," as he refers to Hitler privately, is a mortal danger to both the German Army and State. The two officers are convicted an sentenced, at L-V's insistence, to long prison terms.

L-V immediately consults with his two compatriots, von Seeckt and Groener, and persuades them that the Nazis must be stopped by any means necessary. The three Generals begin laying the groundwork for a coup d'etat. The Generals covertly contact many mid-level officers, securing their loyalty and directing them to report any unusual activity by the Nazis.

1932: The crisis arrives in the form of presidential elections. There are two leading candidates, Hindenburg and Hitler. Neither is acceptable to the Generals: Hitler, they are convinced, is more dangerous than ever and Hindenburg is lapsing in and out of senility. The Generals are appalled at the prospect of Hitler becoming president, and fear that the octogenarian Hindenburg would be in the grip of what they are referring to as the "Nazi-Communist Reichstag." The time has come to act.

Part the Second: The Coup d’etat

Midnight, March 10, 1932: The Generals spring into action. Von Seeckt and Groener order Reichswehr units in Berlin and other major German cities seize control of the post offices, radio stations, and government buildings. The Reichstag building is captured, and, in the morning, the deputies barred from entrance. Hindenburg is confined to his home. The Generals confront him in the early morning hours and ask his blessing for the coup. The old Fieldmarshall refuses to violate his oath to the Republic, but agrees to remain silent. Chancellor Bruening similarly refuses to acknowledge the coup and is placed under house arrest.

LV broadcasts a radio message announcing the coup to Germany. In his "Message to the German People," he announces that the Army carried out the coup to preserve "traditional German dignities and liberties" from destruction by revolutionary forces from the right and left. All political parties that do not affirm their loyalty to the new regime will be barred from the Reichstag.

Political reaction is swift: the parties of the Center and Left denounce the coup. The Socialists and Communists call for a general strike. A fierce debate ensues within the Nazi leadership: Gregor Strasser and Ernst Roem want to send the Brownshirts in to the streets and oppose the Army by force. Hitler temporizes, the orders the NSDAP Reichstag deputies to affirm their loyalty to the Generals. Better to be within the government than to be outlawed. He also hopes that, by acknowledging the coup, he can show the German public that the NSDAP is no threat to the Army.

Other right-wing parties also agree to work with the new regime and are seated in the Reichstag. The veterans private army, the Stahlhelm, places itself at the service of the Generals. It and the Army are instrumental in breaking up anti-coup demonstrations and strikes during the next weeks.

The Generals Consolidate Their Power:

When the "Generals’ Reichstag" convenes, it accepts Hindenburg’s and Bruening’s resignations (the latter coerced, the former out of fatigue). LV is appointed interim Chancellor and Von Seeckt as interim President. Groening remains in his office as Defense Minister. The terms of the President and Chancellor are extended indefinitely, and the President’s right to rule by decree is similarly confirmed without limit. Hitler seethes on the sidelines, but orders Nazi deputies to vote with the majority, fearing (rightly), that the Party will be outlawed and suppressed if it fails to cooperate.

The German populace reacts to the coup and subsequent events with relief: the Republic was paralyzed and lacked the confidence of the people, and the Army was the only institution they trusted. LV, a national hero, is viewed as a paragon of honesty and respectability. Sporadic street-fighting ensues as the Communists and Socialists push their efforts to overthrow the Generals. The Army and the Stahlhelm crush the rebellions; the SD stays at home. Within a month, calm has returned to Germany and the Army is firmly in control.

The split within the NSDAP does not heal: Roehm and Strasser now thoroughly distrust Hitler, believing that he is angling for a position in the military government, and is planning to sell them out to the conservatives. Hitler is, indeed, looking for an office within the Generals’ inner circle, hoping to sabotage from within their efforts to restore prosperity to Germany, then take the first available opportunity to seize power. The Generals rebuff Hitler’s overtures.

Locked out of power, with seemingly no way in, Hitler bides his time and considers his options.

Part the Third: Consolidation, Placation, and Conspiracy

Throughout early 1932, the Generals consult with and reassure the powers that be in Germany: big business, the Catholic political parties, the Junkers and the Church. The heads of the major industrial concerns back the troika with enthusiasm, especially after hearing about the regime’s economic plans. The large landowners are told that junta has no land reform agenda and will continue protectionist policies against agricultural imports. The "Vons" happily sign on.

The Catholic political parties continue to refuse to return to the Reichstag. The parties are in disarray, however, and cannot mount any serious opposition. The Catholic hierarchy backs the Generals, taking much of the popular enthusiasm out of their parties’ opposition. The Protestant churches’ fears are ameliorated after they hear that, unlike the NSDAP, the Generals plan to leave religious and moral issues to the religious authorities.

Groener reorganizes the police power in Germany: by decree, the state police forces are dissolved and replaced by a large paramilitary gendarme controlled by the Berlin government.

Von Papen, the Generals’ new foreign minister, makes the rounds in the European capitals, reassuring France and Britain that Germany has no designs "contrary to the interests of justice and peace in Europe." Meeting secretly with Molotov, Von Papen and the Soviet Commissar agree to continue Germany’s secret military cooperation with the USSR.

The only organized political forces in Germany that continue to stand against the regime are the NSDAP, the Social Democrats (backed by the powerful labor unions) and the Communists. The generals turn on the unions first.

May 1, 1932: on international labor day, the junta hammers the unions. With thousands of workers in the streets, Army units raid various union headquarters, seizing the buildings and the membership records. The government also confiscates the labor unions’ bank accounts, promising to hold them in trust for the "German workers" and out of the "grasping hands of the internationalist, communist-controlled union leadership." Labor leaders are arrested. The junta founds new "national" (i.e. government-controlled) unions, which work hand in glove with big business. The power of the once-powerful German labor organizations is broken. With their collapse, the Social Democrat and Socialist parties fold as effective organizations.

Only the NSDAP remains. The Party leadership is split: the breaking of labor has outraged Strasser and Roehm, who again demand to take the brownshirts into the streets against the Army. Hitler is in a quandary: out in the cold with the regime and lacking any alternatives. His grip on the party is slipping. Goering and Goebbels back Hitler, but their enthusiasm is waning during the months of inactivity.

Having baited the trap, L-V springs it. On October 15, he issues a decree banning all paramilitary organizations (excepting the Stahlhelm, which is deputized as an auxiliary to the police). At a meeting of the top Nazi leadership, Roehm and Strasser confront Hitler. They demand action. Hitler is alone; Goering and Goebbels avoid the meeting. The SD leadership have their way and plans for a Nazi putsch are in the making.

Part the Fourth: Caught Flat-Footed

On October 16, Roehm calls on the Brownshirts to assemble in Berlin, Nuremberg, and Munich on October 18 to protest the ban. The Generals cannot believe their luck, and begin assembling the Reichswehr, the Stahlhelm and the paramilitary police to attack and seize the SA when it assembles.

Roehm, however, is too clever by half, and on midnight the night of the seventeenth, he and hundreds of heavily armed Brownshirts invade the Reichstag, the Defense Ministry buildings, the Chancery and the Presidential palace. Groener is caught napping and is captured by the SA. With the help of his bodyguards, L-V shoots his way out of the Chancery and flees to the safety of the Potsdam garrison. Von Seeckt is killed in the battle for the Presidential palace.

Groener is held hostage as Strasser and his troops seize a radio station and broadcast a call to all SA units in the country to march on Berlin and battle the "reactionary forces who have subverted the army and oppressed the German workers." The next morning, tens of thousands of Brownshirts are seizing trains and trucks and making their way to Berlin. Some units, who had already arrived for the "protest" invade and take over the municipal buildings in Munich and Nuremberg. All over Germany, the SA is running riot, smashing Jewish homes and businesses and attacking the police, Army, and Stahlhelm units.

Roehm, now joined by Hitler, Goering and Goebbels, (belated converts when success seems near) proclaims the dissolution of the military government and the formation of a new cabinet, which will exercise legislative powers "until new elections can be held" at some unspecified date.

L-V, however, is telegraphing (the SA has not cut the lines) and radioing orders from Potsdam to Army and police units throughout the Reich. The police are to suppress the local SA insurgents, while all available Reichswehr units are to converge on Berlin.

Throughout October 18, the junta’s counterattack is in full sway, with the police and their Stahlhelm auxiliaries battling the Brownshirts in every major city in Germany. Machinegun and rifle fire blaze in streets. Hundreds are killed on both sides as governmental forces retake the central Munich police station and municipal buildings. The police attack in Nuremberg is ill-coordinated, and the rebels repulse the police from behind barricades. Government aircraft, the fruits of the secret cooperation with the Russians, strafe and in some cases bomb, trains carrying SA units to Berlin.

In Berlin, thirty thousand Brownshirts, under Strasser’s personal command, take up positions at key points throughout the city. Most are armed with rifles and a scattering of machineguns and mortars, either from the Nazis stockpile or from armories looted in the city. Thousands of others, however, wield nothing but pipes and "Goebbels cocktails."

At three a.m. in the morning on the nineteenth, the Army attacks. General Kurt von Schleicher commands the assault [point of AH irony: in OTL, he was killed by the SS during the "Night of the Long Knives"]. Dozens of armored cars (also developed in coordination with the Russians) spearhead the assault, followed by storm troopers armed with rifles, submachine guns and flamethrowers. Artillery is called in to reduce SA street barricades. Berliners hunker down in their cellars and await the outcome of the civil war raging in the streets above.

Part the Fifth: Denouement at Nuremberg

October 19-21: In Berlin, the Army fights its way towards the governmental complex, street by street and house by house. Spurred on by Strasser’s battlefield leadership, the SA puts up vigorous resistance, even though it is hopelessly outgunned by the Reichswehr. The Army’s tanks and armored cars, as well as superior fire discipline, tell the tale, and by nightfall on the twentieth, the government forces are closing in on the Reichstag buildings, as well as the Presidential palace and the Chancery.

Leading from the front, Strasser is killed in the fighting. In the Presidential palace, panic reigns: the Nazi conspirators know that they face the hangman’s noose if captured, and their hopes of defection by the younger Reichswehr officers have been dashed. Goebbels and Goering favor fleeing to Rome and forming a government in exile. Hitler, however, refuses to leave German soil. Personal relations among the Nazi leadership collapse, and they decide to split up to lessen the risk of the whole group being captured at once.

On the morning of October 21, Hitler flees east, and eventually makes his way to Danzig. Goebbels and Goering head south, making it eventually to Switzerland and then on to Fascist Italy. Roehm, refusing to give up hope, escapes Berlin in disguise, hoping to make his way to Nuremberg. He is spotted by an Army patrol outside the city and captured.

Abandoned and leaderless, SA resistance in Berlin collapses, and L-V enters the city, personally raising the German flag over the Presidential Palace while surrounded by cheering soldiers and civilians. Newsreel footage of this event is shown throughout the nation, and, on the twenty-first, once an operable radio station is found, L-V proclaims to the nation that the Army is once again in control of the capitol.

On October 22, the Brownshirts in Nuremberg, who had been successfully holding off the police and the Stahlhelm, learn that Strasser is dead and Roehm captured, surrender. In the parts of the city under SA control, corpses of Jews are found hanging from the lampposts, their homes and shops sacked and burned by the SA. Middle class Germany recoils in horror at the newsreel footage of the murdered civilians.

L-V, now in undisputed control of the government, forces Groener’s resignation ("on grounds of ill-health" due to injuries suffered at the hands of his Nazi captors), Von Schleicher replaces him as Defense Minister, and by a unanimous vote of the puppet Reichstag (voting in the ruins; a very dramatic scene) L-V assumes the Presidency as well as the Chancellorship.

Martial law is now further tightened. All major offenses are tried by military courts, and all Nazi publications are suspended indefinitely. The surviving SA members are forced to renounce their allegiance to the NSDAP, and membership in the Nazi party is declared to be an capital offense.

The funeral for von Seeckt is suitably elaborate for the fallen President, and Roehm’s show trial is spectacular. The Nazi menace is put on full display, in radio broadcasts, newspapers, and newsreels. L-V has the public fully behind him for his crackdown on what remains of the NSDAP.

Hitler is in hiding in Danzig, where the free city government promises L-V to extradite him if he can be found. Goebbels and Goering continue their farcical government in exile from Rome. Mussolini, in a display of fraternal good will to his fellow fascists, refuses multiple German deportation requests. Roehm is executed in December.

Heinrich Himmler, leader of the SS, takes overall command of the NSDAP, and begins laying the groundwork for a covert Nazi movement.

Part the Sixth: Quiet Times and a Modest Proposal

Firmly ensconced as head of state as well as head of government, Lettow-Vorbeck now starts to pay back the chits he had outstanding. To the big industrial concerns, he gives a wholesale repeal of the antitrust laws, and grants industry organizations the power to jointly set prices and wages. Strikes are effectively outlawed by decrees that only the "official" labor unions can call them and, as noted previously, these are effectively arms of government and big business. Public works projects are instituted, sopping up some of the unemployed labor, and both industry and the military clamber for rearmament, but L-V insists upon waiting for the international situation to improve.

During the Nazi putsch, L-V had moved troops into cities in the demilitarized Rhineland. L-V contacted French President Lebrun, and informed him that the troops were present for internal security purposes only. After the crisis passes, L-V again contacts Lebrun, and argues that the troops must remain in the Rhineland, lest it become a "hotbed of Nazi and Communist agitation." Renaud reluctantly agrees after L-V assures him that no tanks or heavy artillery will be moved into the area. L-V thus accomplishes two things: the British are furious at the French for not being consulted, and the Rhineland is remilitarized without fanfare and without crisis. The acknowledgement that Germany has a few "armored security vehicles," as they are referred to, does not unduly disturb the French or British, although they are exist in apparent violation of the Versailles Treaty.

In the international arena, Germany plays the role of model European citizen. L-V declares on a number of state occasions that his primary goal is recovery from the Depression and restoration of "law and order" to Germany. When pressed, he declines to promise the Powers that Germany is disinterested in restoring its pre-1918 borders, but suggests that he cannot give such assurances for domestic political reasons, "Should I make such a statement aloud," L-V tells Anthony Eden, "the Army would have me on the street in a fortnight." Privately, he approaches the French and British leadership and suggests common cooperation against "fascist and communist agitation and subversion."

Germany maintains its distance from fascist Italy. L-V frequently refers to Mussolini as "that strutting ape," and comments that he and his old African unit could be in Rome while the Italian army was still putting its boots on. German military cooperation continues with the Russians, although L-V is rapidly losing enthusiasm for the project. "Working with that atheist Georgian bank-robber, as L-V refers to Stalin, "demeans Germany and makes me feel dirty."

In May, 1933, L-V feels secure enough in his power to make a foreign trip. He travels to London, where he meets with Eden and discusses the overall European situation. He also meets with his old adversary from the African campaigns, Jan Smuts. L-V makes a very favorable impression on the British public, especially after his amiable and nostalgic reunion with Smuts. British hospitality also impresses L-V, and he leaves with very strong feelings towards England.

On May 16, Franklin Roosevelt proposes a general reduction in armaments, including a total ban on bombers and tanks. The next day, L-V addresses the Reichstag and announces that Germany accepts President Roosevelt’s proposal and is willing to join in any "general armament reduction regime."

Of all the world leaders, L-V notes, only he knows first-hand the "terrors" and "horrible waste of war."

"Germany is already effectively disarmed," L-V states, "and it would welcome equality with other states in abolishing the scourge of armed conflict forever." L-V’s comrades in the Reichswehr are horrified. Immediately after L-V’s speech, plans for another coup are in the making.

Part the Seventh: Told You So.

Throughout May and June of 1933, Lettow-Vorbeck stumps for disarmament. In the Saar, temporarily detached from the Reich and scheduled to have a referendum on its status in 1935, L-V states publicly that Germany will abide by the outcome of the vote and, that Germany "has no desire for one square inch of French soil, including Alsace-Lorraine." Since "Germany has no quarrel with France, France should not fear disarmament . . . unless France has some quarrel with Germany."

Von Papen visits Washington and meets with Roosevelt, who welcomes Germany’s "conversion to the cause of peace." The European powers are markedly less enthusiastic. Peace organizations in France and Britain stage rallies in favor of the treaty, but both governments consider ways to reject the agreement while appeasing public opinion.

On June 21, Japan formally rejects the disarmament proposal. This provides the French and British the excuse they need. The British state that they must "regretfully" decline the proposal. The next week the French also decline to discuss disarmament.

On June 30, L-V again addresses the Reichstag. He rues that "the hand that Germany extended to Europe has been refused."

"If Germany and the other powers cannot be equally disarmed," L-V states, "then Germany and Europe must be equally armed." Germany’s signature to the Versailles Treaty’s arms-limitation provisions is to be considered "withdrawn" from this day forward. "Germany will rearm, consistent with her dignity and position in Europe."

This is the big gamble. If the Western Powers act decisively, Germany, even with its secret arms programs, will be helpless.

Shortly after the speech, the German ambassador in London approaches the British government and proposes an agreement: Germany will unilaterally limit its navy to 35% the size of the Royal Navy. The British grasp this proposal, and within a week, the Anglo-German Naval Accord is signed. Abandoned by the British, the French protest German rearmament, but do not move.

Under the pretext of discussing the military buildup, L-V calls into his office the leadership of the General Staff, which was involved in the conspiracy against him: von Fritch, Blomberg, and Keitel. He confronts them with their "treasonous behavior" and demands an "explanation." The three generals confess their plot. In the old days, L-V says sternly, they would find a pistol in each of their desks, and no further discussion would be necessary. Magnanimously, and to the Generals’ astonishment, L-V pardons them, because, he says, they acted in what they thought was in the best interests of the Reich. The Generals pledge their "eternal loyalty" to L-V.

With both the government and the Army in his back pocket, L-V commits Germany to building up its military in full view of the world. With the renunciation of the Versailles "diktat," his standing soars ever higher with the German public.

Part the Eighth: Intermezzo

1933-35: Lettow-Vorbeck concentrates on two things: the buildup of the German Army and preempting any British and French sanctions for the buildup. He scrupulously adheres to the provisions of the Anglo-German Naval Accord. L-V’s concern is not with the Navy: "The Kaiser’s biggest mistake," he confides to von Fritch, "was attempting to challenge British naval supremacy. It alienated England, and when the day of decision came, meant nothing." Besides, the Army needs the money. No heavy (i.e. seagoing) submarines are laid down, but keels, engines and equipment are secretly stockpiled. He buys off the Navy with a couple of showpiece battleships and one aircraft carrier, the Tirpitz, which he christens himself in 1935.

German unemployment plummets as the buildup roars on. Tanks and guns roll of the Krupp assembly lines at a furious pace. The German Army Air Corps comes out of hiding, equipped with the latest fighters and bombers. Work begins, also, on the Western Wall, the series of fortifications near the border with France. In May of 1934, L-V takes a momentous step: he reinstitutes conscription. The French and British are strangely quiescent.

The Nazis, under Himmler’s leadership, but technically loyal to the "government in exile" in Rome, begin a terrorist campaign aimed at causing the regime to become intolerably oppressive, and thereby triggering a general uprising. Bombs detonate at police stations, governmental offices, and officer’s quarters. The regime institutes swift countermeasures, resulting in the arrests and incarceration (without warrant or trial) of hundreds of suspected Nazis. Infiltration of the Nazi underground is difficult because it is divided into cells, but information gathered seems to point to the movement receiving support from abroad.

In foreign policy, L-V continues to make a show of seeking disarmament, confident that none of the other great powers will take him up on his offer. He also issues feelers to the World War One Allies, seeking the return of Germany’s former colonies. All his initiatives are rebuffed. Nonetheless, he makes special efforts to cozy up to England, where he is a Conservative Party favorite for his strong anti-communist and anti-fascist stands and the naval treaty.

The European situation remains largely calm until late 1934, when Italian troops clash with Ethiopian forces at Ualval, beginning Mussolini’s conquest of one of the last independent parts of Africa. On January 7, 1935, the Laval government in France secretly agrees to let Italy take Ethiopia. By mid-February, the Italians’ offensive is in full swing.

Lettow-Vorbeck, seizing the opportunity to further improve relations with Great Britain, backs a League of Nations resolution condemning Italian aggression and proposing trade sanctions against the Italians. With German backing, the British close the Suez canal to Italian shipping. The logistical situation of the Italian forces becomes increasingly pinched.

In 1935, after a decisive plebiscite vote, the Saar rejoins Germany. Lettow-Vorbeck, who is from the area himself, addresses a huge rally after the election, promising that Germany is "on the road to greatness" and that the other nations of Europe need fear nothing from Germany, since a stable Reich is a peaceful Reich. After the Saar plebiscite, German communities in other territories lost after World War 1 begin organizing and agitating for similar treatment.

With military cooperation with the Soviets abruptly ended, relations between German and the USSR cool decisively. L-V’s public rhetoric grows decisively anti-Soviet. Germany’s relationship with Mussolini’s Italy are even colder; each Nazi terrorist attack generates a new German demand that the Nazi leadership be extradited, or at least expelled, from Italy. Mussolini steadfastly refuses, thus preserving his image as leadership of international fascism and a strongman capable of standing up to foreign "reactionary" powers.

Hitler continues to live a fugitive’s existence in Danzig, where he is hunted by an increasing numbers of German agents infiltrated into the free city.

Part the Ninth: Isolate and Neutralize

1935-1936: With the revelation of the Laval-Mussolini agreement on Ethiopia, the break between France and Britain is complete. The Royal Navy, reinforced by German vessels, stares down the Italian threat in the Mediterranean. The French participate in the League of Nations boycott of Italy, double-crossing Mussolini, but the effort is led by the Anglo-German "entente." In 1936, Chamberlain assumes the Prime Ministership. Their supply situation growing desperate, and the Ethiopians receiving additional supplies and munitions from the League powers, the Italian forces under Bagdolio retreat into Italian Somaliland. With the disgrace of defeat, Bagdolio is forced to resign, the scapegoat for the Duce’s failure. However, events arise that offer Mussolini an opportunity to salvage Italy’s prestige.

In July of 1936, the Spanish Moroccan garrison mutinies against the leftist Madrid government. The revolt, led by General Francisco Franco, begins the Spanish Civil War. Mussolini, seizing the opportunity to expand his influence, backs the rebels. After much heated domestic debate, France and Great Britain call for non-intervention and propose an international arms embargo. Stalin backs the Spanish government and rushes aid to the Republican forces.

Lettow-Vorbeck is torn: he wants to contain Bolshevism, but also desires to stay in good with the Western powers and despises Mussolini. He overrides the opinions of several of his top advisors and throws in with France and England in backing the arms embargo. Notwithstanding the efforts of what people in the know are calling The Big Three (Germany, the United Kingdom, and France), Franco’s forces and their Italian allies continue to push the Republicans back towards Madrid.

Towards the end of 1936, however, it is events in Eastern Europe that capture the attention of Europe. The German agents that have been hunting for Hitler have been moonlighting: the Free City of Danzig rises against its League government.