Post by lordroel on Dec 3, 2021 10:02:44 GMT

Banana Wars (1898-1934)

The Early Years (1898–1904)

Fresh of their decisive international victory over the Spanish Empire in 1899, the United States immediately moved to secure its interests in the region. While the Spanish had not been a serious world power for some time at the outbreak of the Spanish American War, their influence in the Caribbean and Central America were still being felt until the 20th century.

Following the end of the war, the US wanted to wrest control of the Caribbean from Spain and put it firmly under American influence for the first time ever. The first countries to feel the pressure of the United States were Cuba and Panama who had long been coveted as strategic positions both economically and militarily in the region.

Cuba fell under American military occupation in 1899 following the end of the Spanish American War. Despite being a key war goal, the United States had agreed to allow Cuba to remain autonomous after the war as not to upset the international community. The United States could not legally annex Cuba, long a goal of jingoistic Americans throughout the 19th century, so they instead moved to exert an out-sized amount of influence over the island nation.

The initial occupation lasted from 1899–1902 as part of the agreement laid out in the Treaty of Paris in 1899. The United States oversaw the creation of the Republic of Cuba which was officially born in 1902. However, during the initial legal occupation, the United States Congress passes a bill which contains something called the Platt Amendment.

The Platt Amendment was quietly passed with in a larger bill and drastically changed the terms in which the United States would leave the island. The bill severely hampered the new Cuban nation from negotiating or entering treaties with other foreign powers other than the United States. It also gave the United States an almost entirely free hand in interfering with Cuban affairs in the interest of protecting “Cuban independence”. The stipulations of the Platt Amendment are added to the Cuban constitution in 1902 which paves the way for US withdrawal from the island but also opens the door to future intervention by American troops.

At the same time, the United States is working behind the scenes to help orchestrate the Panamanian separation from Columbia. Their work comes to fruition in 1903. While the United States did not overtly enter into this struggle, their finger prints are clearly visible. This becomes expressly apparent when one of the first things the newly independent Panamanian nation does is sign the Hay–Bunau-Varilla Treaty. This treaty established the creation of the Panama Canal Zone and initially promises United States control of the Panama Canal and the land directly surrounding it “in perpetuity”.

In four short years following the cessation of the Spanish American War, the United States has legally codified its ability to interfere in Cuba and Panama for the foreseeable future and begins to patrol the waters in the Caribbean with navy ships and marines in order to “protect US interests” in the region. The vacuum the Spanish left following their demotion on the world stage is quickly filled by the United States in the Western Hemisphere.

Carrying the Big Stick (1905–1920)

President Teddy Roosevelt is famous for many things but one of them was his foreign policy. He summed up his foreign policy in the now eternal words “speak softly and carry a big stick; you will go far”. The period starting with Teddy Roosevelt’s presidency in 1901 sees the use of America’s stick a lot in the Caribbean.

Cartoon: William Allen Rogers cartoon depicting Theodore Roosevelt's Big Stick ideology

After pursuing their legal routes the United States begins to find excuses and incidents in order to intervene in neighboring countries. This period of ramping up involvement in the region sees the United States military get involved in Cuba again, the Dominican Republic, Honduras, Nicaragua and Haiti. The geopolitical scene in Central America was chaotic following the Spanish withdrawal from the region leading to many revolutions, wars, rebels and other instability that was spreading through these nascent nations. The United States used this instability as reason to get involved. And get involved they did.

The increasingly lucrative export of bananas and other valuable cash crops in Central America began to pick up steam at the turn of the century as more modern modes of business and transportation began to percolate through the region. Large companies began to construct their own ships and railroads in order to export their crops from Nicaragua and Honduras. These infrastructure projects were private and not public leading them to be considered vital private interests in the region — something the United States said they would protect from harm.

In 1912 a revolution struck Nicaragua and the besieged Nicaraguan president invited the United States to intervene on his behalf. The US sent in over 2,000 regular troops and marines to beat back the insurgency. The conflict resulted in the regime keeping its power and in return ceded the majority of control the Nicaraguan financial sector to United States interests.

In neighboring Honduras, a similar takeover was taking place. Through a campaign of vertical integration three fruit companies had began to take control the country’s infrastructure, financial system and agricultural land. As in Nicaragua, the ownership and capital involved in these ventures were overwhelmingly foreign and the majority of the money was being made outside of the country’s themselves.

These large foreign companies with their massive amounts of so called “private property” and “vested interests” called on the United State’s help in all manner of problems from domestic disputes with local authorities to international issues over land rights and sovereign territory. The United States answered the call. Honduras for example, was invaded by US forces seven times between 1903 and 1925.

In the Caribbean, the American’s invaded Cuba once again in order to protect the all important American interests on the island and to oversee the election of a new pro-American president. That intervention lasted two and a half years between 1906 and 1909.

In 1915, the United States invades Haiti in order to protect American interests following the assassination of the Haitian president. Woodrow Wilson, sends in over 300 Americans to occupy the capital city of Port-Au-Prince with the aim of protecting the Haitian American Sugar Company. In 1917, the United States oversees the creation of a new constitution in Haiti that loosens restriction on foreign investment and land ownership in the country opening the door to the expansion of American companies on the island.

Photo: United States Marines with a Haitian guide patrolling the jungle in 1915 during the Battle of Fort Dipitie

The Haitian occupation would start a long campaign on the island that was fraught with racism, unpopularity and heavy handed control of the population via various pro-American puppet regimes.

This ramping up period of the Banana Wars is marked by American interest in the lucrative agricultural trade of the region. The expansions of the railroads and safer seas around the Caribbean made trade easier and more profitable than ever before and the United States had no intention of allowing the profits flow into local and native coffers.

This interest in agriculture not only gave this turbulent period its name but also started a viscous cycle that looked as though it could go on forever. The United States and associated companies would weather local instability, they would use their assets and interests as an excuse to go in and secure or quell the trouble, the aftermath ceded more rights and capital to the foreign companies which would then have more exposure to future instability and the whole thing started over again.

The instability was never allowed to naturally stabilize due to the large amount of money flowing out of the country and the United State’s inability to allow for a natural government to emerge.

Interventionism and Backlash (1921–1934)

By the early 1920s the United States was heavily involved or occupying the Dominican Republic, Honduras, and Haiti. Pro-American governments had been established in Cuba and Nicaragua as well as Panama. The US military had been making overt excursions into Mexico at the tail end of the 1910s to pursue guerillas in the northern part of the country along the US-Mexico border. American involvement in the region was at its peak and at its most heavy handed during this period.

Following the end of WWI in 1919, American sentiment against interventionism began to change. Seeing the aftermath of the war and the conflict that global empires had caused, people in the United States began to turn against the idea of occupying countries such as Haiti and the Dominican Republic.

The United States began planning to put in place more permanent pro-American governments in the occupied territories in order to try and pullout without losing their control over the interests in each country. The United States oversaw the election of an overwhelmingly pro-American president and congress in the Dominican Republic in 1924 before withdrawing their troops.

Photo: The Flag of the United States waving over Ozama Fortress, c. 1922

They had similar plans for Haiti but continued insurgency and guerilla fighting in the country prevented a secure American government from being established.

In 1927 the United States once again entered Nicaragua to try and quell a growing civil war. They did not leave that country until 1932 and even then troops were left behind to protect American interests.

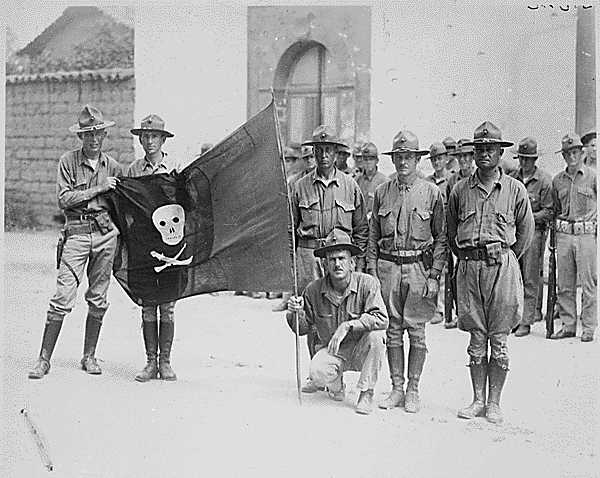

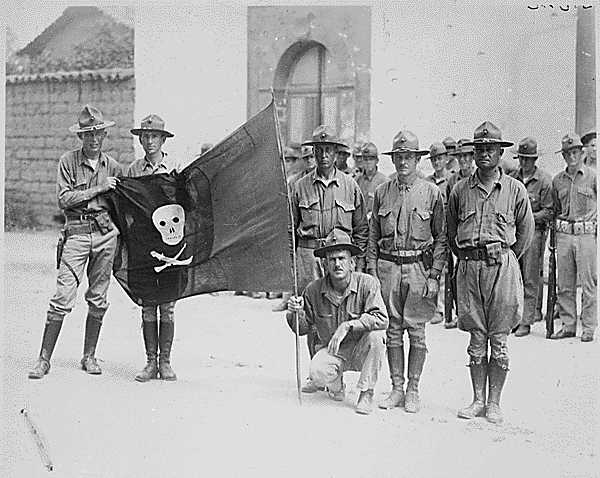

Photo: US Marines with the captured flag of Augusto César Sandino in Nicaragua in 1932

The American public’s taste for foreign intervention crashed in 1930 as the Great Depression took hold in force. In Europe and Asia fascistic powers began to rise and flex their muscles regionally and Americans at home returned to an overwhelmingly isolationist policy. This extended from involvement in Europe to involvement in the Caribbean.

Sensing the changing American attitude towards foreign policy Franklin Roosevelt runs on a platform of non-interventionism and coins the term Good Neighbor Policy to describe his desire to withdraw from local countries and return to being good diplomatic neighbors.

Being a Good Neighbor, Ending the Banana Wars (1934)

President Roosevelt declared in 1934 a whole scale change to American foreign policy in Latin America. In 1933 he announced a cessation to all US military activity in Nicaragua. In 1934 he announced the withdrawal of US troops from Haiti, ending a nearly 20 year conflict in the country. He also rewrote the treaties governing US-Cuba relations and made it much more difficult for the US to intervene in their neighbor’s politics. In 1938 Roosevelt negotiated a compensation package to the Mexican government for US actions in their country up to that point. His new policy was true to form and focused on making the United States a good neighbor to the smaller, poorer nations in the region.

“No state has the right to intervene in the internal or external affairs of another.” — President Roosevelt, 1933

President Roosevelt managed to enact his policy with relative success in the middle 1930s as he oversaw a large scale drawback of United State’s military and economic occupations of many Latin American countries. He came out vocally against armed intervention in Latin America and returned America to their more traditional position of regional counselor and isolationist power.

If not for a stark change in American sentiment and the decisive action by President Franklin Roosevelt, the cycle of instability and intervention in Latin America could have continued indefinitely.

Legacy

YouTube (Banana Wars - US Marines Occupy Cuba, Haiti & Dominican Republic)

Following the Spanish-American War, the United States foreign policy, under the influence of the Monroe Doctrine, intervened in several countries in Central America and the Caribbean. The United States Marine Corps was usually the military arm of these involvements as was the case in Cuba, Haiti and the Dominican Republic

Interventions

Panama: U.S. interventions in the isthmus go back to the 1846 Mallarino–Bidlack Treaty and intensified after the so-called Watermelon Riot of 1856. In 1885 US military intervention gained a mandate with the construction of the Panama Canal. The building process collapsed in bankruptcy, mismanagement, and disease in 1889, but resumed in the 20th century. In 1903, Panama seceded from the Republic of Colombia, backed by the U.S. government, during the Thousand Days' War. The Hay–Pauncefote Treaty allowed the US to construct and control the Panama Canal. In 1903 the United States established sovereignty over a Panama Canal Zone.

Spanish–American War: U.S. forces seized Cuba and Puerto Rico from Spain in 1898. The end of the Spanish–American War led to the start of Banana Wars.

Cuba: In December 1899, U.S. president William McKinley declared Leonard Wood, a United States Army general, to have supreme power in Cuba. The U.S. conquered Cuba from the Spanish Empire. It was occupied by the U.S. from 1898 to 1902 under Wood as its military governor, and again from 1906 to 1909, 1912, and 1917 to 1922, subject to the terms of the Cuban–American Treaty of Relations (1903) until 1934. In 1903 the US took a permanent lease on the Guantanamo Bay Naval Base.

Dominican Republic: Action in 1903, 1904 (the Santo Domingo Affair), and 1914 (Naval forces engaged in battles in the city of Santo Domingo; occupied by the U.S. from 1916 to 1924.

Nicaragua: Occupied by the U.S. almost continuously from 1912 to 1933, after intermittent landings and naval bombardments in the prior decades. The U.S. had troops in Nicaragua to prevent its leaders from creating conflicts with U.S. interests in the country. The bluejackets and marines were there for about 15 years. The U.S. claimed it wanted Nicaragua to elect "good men", who ostensibly would not threaten to disrupt U.S. interests.

Mexico: U.S. military involvements with Mexico in this period had the same general commercial and political causes, but stand as a special case. The Americans conducted the Border War with Mexico from 1910–1919 for additional reasons: to control the flow of immigrants and refugees from revolutionary Mexico (pacificos), and to counter rebel raids into U.S. territory. The 1914 U.S. occupation of Veracruz, however, was an exercise of armed influence, not an issue of border integrity; it was aimed at cutting off the supplies of German munitions to the government of Mexican leader Victoriano Huerta, which U.S. President Woodrow Wilson refused to recognize.

In the years prior to World War I, the U.S. was also alert to the regional balance of power against Germany. The Germans were actively arming and advising the Mexicans, as shown by the 1914 SS Ypiranga arms-shipping incident, German saboteur Lothar Witzke's base in Mexico City, the 1917 Zimmermann Telegram and the German advisors present during the 1918 Battle of Ambos Nogales. Only twice during the Mexican Revolution did the U.S. military occupy Mexico: during the temporary occupation of Veracruz in 1914 and between 1916 and 1917, when U.S. General John Pershing led U.S. Army forces on a nationwide search for Pancho Villa.

Haiti, occupied by the U.S. from 1915–1934, which led to the creation of a new Haitian constitution in 1917 that instituted changes that included an end to the prior ban on land ownership by non-Haitians. This period included the First and Second Caco Wars.

Honduras, where the United Fruit Company and Standard Fruit Company dominated the country's key banana export sector and associated land holdings and railways, saw insertion of American troops in 1903, 1907, 1911, 1912, 1919, 1924 and 1925. The writer O. Henry coined the term "Banana republic" in 1904 to describe Honduras.

Other Latin American nations were influenced or dominated by American economic policies and/or commercial interests to the point of coercion. Theodore Roosevelt declared the Roosevelt Corollary to the Monroe Doctrine in 1904, asserting the right of the United States to intervene to stabilize the economic affairs of states in the Caribbean and Central America if they were unable to pay their international debts. From 1909–1913, President William Howard Taft and his Secretary of State Philander C. Knox asserted a more "peaceful and economic" Dollar Diplomacy foreign policy, although that too was backed by force, as in Nicaragua.

YouTube (Banana Wars - US Occupation in Central America for A Fruit Company)

US involvement in Central America dated back to the first attempt to build the Panama Canal. And in accordance to the Monroe Doctrine was expanded in the 20th century too. US Marines took part in expeditions in Guatemala, Nicaragua and US naval power was a factor in many disputes like the Coto War between Costa Rica and Panama. With the rise of the United Fruit Company, the US domestic market also influenced decisions in the region

The Early Years (1898–1904)

Fresh of their decisive international victory over the Spanish Empire in 1899, the United States immediately moved to secure its interests in the region. While the Spanish had not been a serious world power for some time at the outbreak of the Spanish American War, their influence in the Caribbean and Central America were still being felt until the 20th century.

Following the end of the war, the US wanted to wrest control of the Caribbean from Spain and put it firmly under American influence for the first time ever. The first countries to feel the pressure of the United States were Cuba and Panama who had long been coveted as strategic positions both economically and militarily in the region.

Cuba fell under American military occupation in 1899 following the end of the Spanish American War. Despite being a key war goal, the United States had agreed to allow Cuba to remain autonomous after the war as not to upset the international community. The United States could not legally annex Cuba, long a goal of jingoistic Americans throughout the 19th century, so they instead moved to exert an out-sized amount of influence over the island nation.

The initial occupation lasted from 1899–1902 as part of the agreement laid out in the Treaty of Paris in 1899. The United States oversaw the creation of the Republic of Cuba which was officially born in 1902. However, during the initial legal occupation, the United States Congress passes a bill which contains something called the Platt Amendment.

The Platt Amendment was quietly passed with in a larger bill and drastically changed the terms in which the United States would leave the island. The bill severely hampered the new Cuban nation from negotiating or entering treaties with other foreign powers other than the United States. It also gave the United States an almost entirely free hand in interfering with Cuban affairs in the interest of protecting “Cuban independence”. The stipulations of the Platt Amendment are added to the Cuban constitution in 1902 which paves the way for US withdrawal from the island but also opens the door to future intervention by American troops.

At the same time, the United States is working behind the scenes to help orchestrate the Panamanian separation from Columbia. Their work comes to fruition in 1903. While the United States did not overtly enter into this struggle, their finger prints are clearly visible. This becomes expressly apparent when one of the first things the newly independent Panamanian nation does is sign the Hay–Bunau-Varilla Treaty. This treaty established the creation of the Panama Canal Zone and initially promises United States control of the Panama Canal and the land directly surrounding it “in perpetuity”.

In four short years following the cessation of the Spanish American War, the United States has legally codified its ability to interfere in Cuba and Panama for the foreseeable future and begins to patrol the waters in the Caribbean with navy ships and marines in order to “protect US interests” in the region. The vacuum the Spanish left following their demotion on the world stage is quickly filled by the United States in the Western Hemisphere.

Carrying the Big Stick (1905–1920)

President Teddy Roosevelt is famous for many things but one of them was his foreign policy. He summed up his foreign policy in the now eternal words “speak softly and carry a big stick; you will go far”. The period starting with Teddy Roosevelt’s presidency in 1901 sees the use of America’s stick a lot in the Caribbean.

Cartoon: William Allen Rogers cartoon depicting Theodore Roosevelt's Big Stick ideology

After pursuing their legal routes the United States begins to find excuses and incidents in order to intervene in neighboring countries. This period of ramping up involvement in the region sees the United States military get involved in Cuba again, the Dominican Republic, Honduras, Nicaragua and Haiti. The geopolitical scene in Central America was chaotic following the Spanish withdrawal from the region leading to many revolutions, wars, rebels and other instability that was spreading through these nascent nations. The United States used this instability as reason to get involved. And get involved they did.

The increasingly lucrative export of bananas and other valuable cash crops in Central America began to pick up steam at the turn of the century as more modern modes of business and transportation began to percolate through the region. Large companies began to construct their own ships and railroads in order to export their crops from Nicaragua and Honduras. These infrastructure projects were private and not public leading them to be considered vital private interests in the region — something the United States said they would protect from harm.

In 1912 a revolution struck Nicaragua and the besieged Nicaraguan president invited the United States to intervene on his behalf. The US sent in over 2,000 regular troops and marines to beat back the insurgency. The conflict resulted in the regime keeping its power and in return ceded the majority of control the Nicaraguan financial sector to United States interests.

In neighboring Honduras, a similar takeover was taking place. Through a campaign of vertical integration three fruit companies had began to take control the country’s infrastructure, financial system and agricultural land. As in Nicaragua, the ownership and capital involved in these ventures were overwhelmingly foreign and the majority of the money was being made outside of the country’s themselves.

These large foreign companies with their massive amounts of so called “private property” and “vested interests” called on the United State’s help in all manner of problems from domestic disputes with local authorities to international issues over land rights and sovereign territory. The United States answered the call. Honduras for example, was invaded by US forces seven times between 1903 and 1925.

In the Caribbean, the American’s invaded Cuba once again in order to protect the all important American interests on the island and to oversee the election of a new pro-American president. That intervention lasted two and a half years between 1906 and 1909.

In 1915, the United States invades Haiti in order to protect American interests following the assassination of the Haitian president. Woodrow Wilson, sends in over 300 Americans to occupy the capital city of Port-Au-Prince with the aim of protecting the Haitian American Sugar Company. In 1917, the United States oversees the creation of a new constitution in Haiti that loosens restriction on foreign investment and land ownership in the country opening the door to the expansion of American companies on the island.

Photo: United States Marines with a Haitian guide patrolling the jungle in 1915 during the Battle of Fort Dipitie

The Haitian occupation would start a long campaign on the island that was fraught with racism, unpopularity and heavy handed control of the population via various pro-American puppet regimes.

This ramping up period of the Banana Wars is marked by American interest in the lucrative agricultural trade of the region. The expansions of the railroads and safer seas around the Caribbean made trade easier and more profitable than ever before and the United States had no intention of allowing the profits flow into local and native coffers.

This interest in agriculture not only gave this turbulent period its name but also started a viscous cycle that looked as though it could go on forever. The United States and associated companies would weather local instability, they would use their assets and interests as an excuse to go in and secure or quell the trouble, the aftermath ceded more rights and capital to the foreign companies which would then have more exposure to future instability and the whole thing started over again.

The instability was never allowed to naturally stabilize due to the large amount of money flowing out of the country and the United State’s inability to allow for a natural government to emerge.

Interventionism and Backlash (1921–1934)

By the early 1920s the United States was heavily involved or occupying the Dominican Republic, Honduras, and Haiti. Pro-American governments had been established in Cuba and Nicaragua as well as Panama. The US military had been making overt excursions into Mexico at the tail end of the 1910s to pursue guerillas in the northern part of the country along the US-Mexico border. American involvement in the region was at its peak and at its most heavy handed during this period.

Following the end of WWI in 1919, American sentiment against interventionism began to change. Seeing the aftermath of the war and the conflict that global empires had caused, people in the United States began to turn against the idea of occupying countries such as Haiti and the Dominican Republic.

The United States began planning to put in place more permanent pro-American governments in the occupied territories in order to try and pullout without losing their control over the interests in each country. The United States oversaw the election of an overwhelmingly pro-American president and congress in the Dominican Republic in 1924 before withdrawing their troops.

Photo: The Flag of the United States waving over Ozama Fortress, c. 1922

They had similar plans for Haiti but continued insurgency and guerilla fighting in the country prevented a secure American government from being established.

In 1927 the United States once again entered Nicaragua to try and quell a growing civil war. They did not leave that country until 1932 and even then troops were left behind to protect American interests.

Photo: US Marines with the captured flag of Augusto César Sandino in Nicaragua in 1932

The American public’s taste for foreign intervention crashed in 1930 as the Great Depression took hold in force. In Europe and Asia fascistic powers began to rise and flex their muscles regionally and Americans at home returned to an overwhelmingly isolationist policy. This extended from involvement in Europe to involvement in the Caribbean.

Sensing the changing American attitude towards foreign policy Franklin Roosevelt runs on a platform of non-interventionism and coins the term Good Neighbor Policy to describe his desire to withdraw from local countries and return to being good diplomatic neighbors.

Being a Good Neighbor, Ending the Banana Wars (1934)

President Roosevelt declared in 1934 a whole scale change to American foreign policy in Latin America. In 1933 he announced a cessation to all US military activity in Nicaragua. In 1934 he announced the withdrawal of US troops from Haiti, ending a nearly 20 year conflict in the country. He also rewrote the treaties governing US-Cuba relations and made it much more difficult for the US to intervene in their neighbor’s politics. In 1938 Roosevelt negotiated a compensation package to the Mexican government for US actions in their country up to that point. His new policy was true to form and focused on making the United States a good neighbor to the smaller, poorer nations in the region.

“No state has the right to intervene in the internal or external affairs of another.” — President Roosevelt, 1933

President Roosevelt managed to enact his policy with relative success in the middle 1930s as he oversaw a large scale drawback of United State’s military and economic occupations of many Latin American countries. He came out vocally against armed intervention in Latin America and returned America to their more traditional position of regional counselor and isolationist power.

If not for a stark change in American sentiment and the decisive action by President Franklin Roosevelt, the cycle of instability and intervention in Latin America could have continued indefinitely.

Legacy

YouTube (Banana Wars - US Marines Occupy Cuba, Haiti & Dominican Republic)

Following the Spanish-American War, the United States foreign policy, under the influence of the Monroe Doctrine, intervened in several countries in Central America and the Caribbean. The United States Marine Corps was usually the military arm of these involvements as was the case in Cuba, Haiti and the Dominican Republic

Interventions

Panama: U.S. interventions in the isthmus go back to the 1846 Mallarino–Bidlack Treaty and intensified after the so-called Watermelon Riot of 1856. In 1885 US military intervention gained a mandate with the construction of the Panama Canal. The building process collapsed in bankruptcy, mismanagement, and disease in 1889, but resumed in the 20th century. In 1903, Panama seceded from the Republic of Colombia, backed by the U.S. government, during the Thousand Days' War. The Hay–Pauncefote Treaty allowed the US to construct and control the Panama Canal. In 1903 the United States established sovereignty over a Panama Canal Zone.

Spanish–American War: U.S. forces seized Cuba and Puerto Rico from Spain in 1898. The end of the Spanish–American War led to the start of Banana Wars.

Cuba: In December 1899, U.S. president William McKinley declared Leonard Wood, a United States Army general, to have supreme power in Cuba. The U.S. conquered Cuba from the Spanish Empire. It was occupied by the U.S. from 1898 to 1902 under Wood as its military governor, and again from 1906 to 1909, 1912, and 1917 to 1922, subject to the terms of the Cuban–American Treaty of Relations (1903) until 1934. In 1903 the US took a permanent lease on the Guantanamo Bay Naval Base.

Dominican Republic: Action in 1903, 1904 (the Santo Domingo Affair), and 1914 (Naval forces engaged in battles in the city of Santo Domingo; occupied by the U.S. from 1916 to 1924.

Nicaragua: Occupied by the U.S. almost continuously from 1912 to 1933, after intermittent landings and naval bombardments in the prior decades. The U.S. had troops in Nicaragua to prevent its leaders from creating conflicts with U.S. interests in the country. The bluejackets and marines were there for about 15 years. The U.S. claimed it wanted Nicaragua to elect "good men", who ostensibly would not threaten to disrupt U.S. interests.

Mexico: U.S. military involvements with Mexico in this period had the same general commercial and political causes, but stand as a special case. The Americans conducted the Border War with Mexico from 1910–1919 for additional reasons: to control the flow of immigrants and refugees from revolutionary Mexico (pacificos), and to counter rebel raids into U.S. territory. The 1914 U.S. occupation of Veracruz, however, was an exercise of armed influence, not an issue of border integrity; it was aimed at cutting off the supplies of German munitions to the government of Mexican leader Victoriano Huerta, which U.S. President Woodrow Wilson refused to recognize.

In the years prior to World War I, the U.S. was also alert to the regional balance of power against Germany. The Germans were actively arming and advising the Mexicans, as shown by the 1914 SS Ypiranga arms-shipping incident, German saboteur Lothar Witzke's base in Mexico City, the 1917 Zimmermann Telegram and the German advisors present during the 1918 Battle of Ambos Nogales. Only twice during the Mexican Revolution did the U.S. military occupy Mexico: during the temporary occupation of Veracruz in 1914 and between 1916 and 1917, when U.S. General John Pershing led U.S. Army forces on a nationwide search for Pancho Villa.

Haiti, occupied by the U.S. from 1915–1934, which led to the creation of a new Haitian constitution in 1917 that instituted changes that included an end to the prior ban on land ownership by non-Haitians. This period included the First and Second Caco Wars.

Honduras, where the United Fruit Company and Standard Fruit Company dominated the country's key banana export sector and associated land holdings and railways, saw insertion of American troops in 1903, 1907, 1911, 1912, 1919, 1924 and 1925. The writer O. Henry coined the term "Banana republic" in 1904 to describe Honduras.

Other Latin American nations were influenced or dominated by American economic policies and/or commercial interests to the point of coercion. Theodore Roosevelt declared the Roosevelt Corollary to the Monroe Doctrine in 1904, asserting the right of the United States to intervene to stabilize the economic affairs of states in the Caribbean and Central America if they were unable to pay their international debts. From 1909–1913, President William Howard Taft and his Secretary of State Philander C. Knox asserted a more "peaceful and economic" Dollar Diplomacy foreign policy, although that too was backed by force, as in Nicaragua.

YouTube (Banana Wars - US Occupation in Central America for A Fruit Company)

US involvement in Central America dated back to the first attempt to build the Panama Canal. And in accordance to the Monroe Doctrine was expanded in the 20th century too. US Marines took part in expeditions in Guatemala, Nicaragua and US naval power was a factor in many disputes like the Coto War between Costa Rica and Panama. With the rise of the United Fruit Company, the US domestic market also influenced decisions in the region