What if: HMS Victorious as a United States Navy carrier (1942)

Feb 19, 2020 17:07:49 GMT

gillan1220 likes this

Post by lordroel on Feb 19, 2020 17:07:49 GMT

What if: HMS Victorious as a United States Navy carrier (1942) Part I

In the October 1942 Battle of the Santa Cruz Islands, the Pacific War’s fourth clash of carriers, the Japanese finally scored a clear victory. Japanese planes sank the American carrier Hornet and crippled her consort Enterprise, leaving the U.S. Navy with no aircraft carriers to cover the ongoing campaign on Guadalcanal.

Vice Admiral William Halsey, the American commander at Santa Cruz, asked his boss Chester Nimitz to request an aircraft carrier from the British Eastern Fleet be loaned to the Americans in the South Pacific. Nimitz passed the request up the line, and after languishing for a couple of weeks in the American naval bureaucracy it reached the Admiralty, who promptly agreed.

The Eastern Fleet had only one carrier at the time, Illustrious. First Sea Lord Sir Dudley Pound offered to send Illustrious and her sister Victorious from the British Home Fleet, in exchange for the American carrier Ranger serving with Home Fleet. Ranger was less capable than the two British carriers and considered too vulnerable to operate against the Japanese, but perfectly adequate to provide fighter cover and ASW support on the Murmansk Run. The Americans demurred, citing a need for a training carrier at home, and Victorious with an escorting cruiser and three destroyers set out for Norfolk, fighting their way through a Force 9 gale to arrive on 31 December 1942 after a stop at Bermuda.

At American insistence, the ship underwent significant changes for Pacific service. She immediately entered drydock upon her arrival in the United States, remaining there until 31 January 1943. Dockyard workers performed an extensive and apparently badly-needed overhaul, and made a number of changes to the ship. Her flight deck was extended by ten feet at the aft end and new American search radars (air and surface), communications gear, homing systems and cypher equipment were installed. She received additional 20mm anti-aircraft guns, expanded mess space and fire-suppression systems in her crew areas.

After a great deal of discussion and bureaucratic wrangling, the Admiralty and the U.S. Navy agreed that Victorious would retain her British air crews, but they would operate American aircraft using American procedures. New arrestor wires were fitted to the flight deck to handle the heavier American planes, and the British deck crew learned American take-off and landing procedures. All of the British crew received American-issued dungarees (for the enlisted men) and khakis (for the officers) to wear while operating in the Pacific.

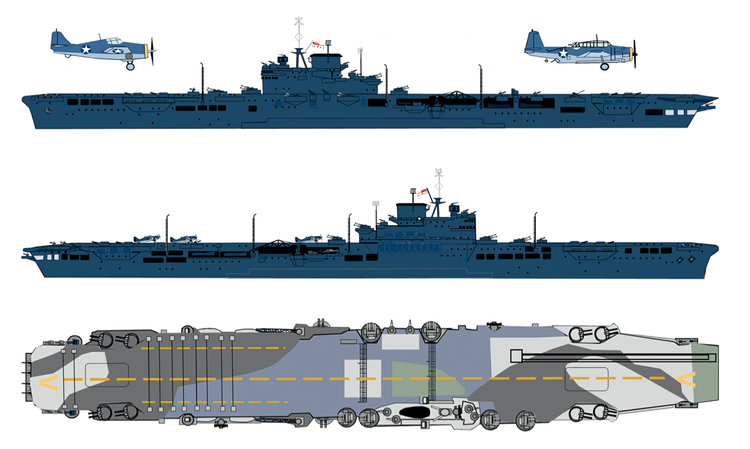

Photo: HMS Victorious in port at Pearl Harbor, the British disruptive camouflage was to be overpainted with sea blue, the U.S. Navy Measure 11 specification.

New Grumman F4F-4 Wildcats and TBM Avengers replaced the Martlets, Fulmars and Albacores that had arrived at Norfolk with Victorious. The F4F-4 was identical to the Martlet IV, and no transition was necessary. The big Avenger was a different story; the ship’s aircraft cranes could not lift the planes when fully loaded, and the Avengers would only just barely fit on the ship’s aircraft elevators. The American liaison team suggested that Victorious fly only fighters, but Capt. L.D. Mackintosh demurred, not wishing to leave his ship without the anti-submarine capabilities of the Avenger. The Americans did not press the issue, and Victorious would operate both fighters and torpedo bombers.

British practice restricted an air group to only those aircraft that could be struck below into the hangar. Now under American command, Victorious added a deck park, increasing her capacity to from 42 planes (24 Martlets and 18 Albacores) to 52 (36 Martlets and 16 Avengers) but requiring that the deck crews learn complicated new procedures to move parked aircraft to allow take-offs and landings.

Together with the American destroyers Pringle, Bache and Converse, Victorious set out from Norfolk on 3 February, conducting flight exercises as she steamed southward. Her official call sign, “Robin,” became the unofficial name applied to her by American and eventually British sailors while she served the U.S. Navy. The Avengers proved just as troublesome in flight as on deck, with two fatal accidents claiming British aircrew.

Victorious barely fit through the Panama Canal, even after her crew removed some of her sponsons and aerials. She exchanged scrapes and gashes with the Gatun Locks, prompting the canal management to present a bill for damages to their facility before she entered the Pacific. Mackintosh scrawled “Lease Lend” across it and handed it back.

Victorious arrived at Pearl Harbor on 4 March, continuing to exercise her air and anti-aircraft crews during the voyage. More Avenger landings proved that the British arrestor system simply could not handle the huge brutes. The carrier went into dockyard hands again at Pearl Harbor to receive new arrestor wires, additional 40mm and 20mm anti-aircraft guns, and a coat of U.S. Navy battleship-gray paint outside and fireproof paint inside. Victorious also received a Coca-Cola dispenser and three ice-cream machines. “Ice cream is always available in large quantities,” Mackintosh reported to the Admiralty in a description of American practices, “and is much appreciated and is looked upon as essential.”

Mackintosh, one of the few British carrier commanders with flight experience - he had served as a Fleet Air Arm observer - insisted on rigorous training for his aircrew. Because the Americans often used cross-deck deployments where planes from one carrier would land on another and operate from there, Victorious had to use the same landing procedures as American ships. American deck crews used a different signaling system and confusion could prove deadly; for example, British and American batsmen (the crewman using brightly-colored paddles to wig-wag landing instructions to the incoming pilots) used the same signal for “Go Higher” and “You Are Too High,” respectively. A Royal Navy batsman had authority over the pilot during landing procedures and could tell him what to do including waving off a landing attempt; a U.S. Navy batsman merely relayed positioning information with final decisions in the pilot’s hands.

Victorious would operate one torpedo and three fighter squadrons in American service; while part of Home Fleet she had flown one torpedo and two fighter squadrons. The Avenger aircrews proved the most troublesome. Many of them had flown the Albacores of 832 Squadron, but were new to the Avenger. Others had been sent to the United States to train on the Avenger, but some of these men were not carrier-qualified when first assigned to Victorious. They had trained at Norfolk, but Mackintosh remained dissatisfied and asked for more time to practice.

Photo: Victorious and her air group at Noumean, New Caledonia. The Fleet Air Arm squadrons carried U.S. Navy markings for this deployment (Victorious deck hands added a small, unauthorized “Royal Navy” stencil).

For the next two months the aircrew trained in American methods, while the anti-aircraft gunners and damage control personnel underwent intensive training as well. Along with the battleship North Carolina, Victorious and her three destroyers left Pearl Harbor on 8 May, arriving in the war zone at Noumea on New Caledonia nine days later. The Royal Navy had entered the Solomons campaign.

Article was published in Avalanche Press and called South Pacific: USS Robin (Part One)

Link of interest: USS Robin: When the CNO Needed a Royal Navy Carrier – Part I and Part II

Ore this link about another What if HMS Victorious as a United States Navy carrier: The ship that never was (USS ROBIN)

In the October 1942 Battle of the Santa Cruz Islands, the Pacific War’s fourth clash of carriers, the Japanese finally scored a clear victory. Japanese planes sank the American carrier Hornet and crippled her consort Enterprise, leaving the U.S. Navy with no aircraft carriers to cover the ongoing campaign on Guadalcanal.

Vice Admiral William Halsey, the American commander at Santa Cruz, asked his boss Chester Nimitz to request an aircraft carrier from the British Eastern Fleet be loaned to the Americans in the South Pacific. Nimitz passed the request up the line, and after languishing for a couple of weeks in the American naval bureaucracy it reached the Admiralty, who promptly agreed.

The Eastern Fleet had only one carrier at the time, Illustrious. First Sea Lord Sir Dudley Pound offered to send Illustrious and her sister Victorious from the British Home Fleet, in exchange for the American carrier Ranger serving with Home Fleet. Ranger was less capable than the two British carriers and considered too vulnerable to operate against the Japanese, but perfectly adequate to provide fighter cover and ASW support on the Murmansk Run. The Americans demurred, citing a need for a training carrier at home, and Victorious with an escorting cruiser and three destroyers set out for Norfolk, fighting their way through a Force 9 gale to arrive on 31 December 1942 after a stop at Bermuda.

At American insistence, the ship underwent significant changes for Pacific service. She immediately entered drydock upon her arrival in the United States, remaining there until 31 January 1943. Dockyard workers performed an extensive and apparently badly-needed overhaul, and made a number of changes to the ship. Her flight deck was extended by ten feet at the aft end and new American search radars (air and surface), communications gear, homing systems and cypher equipment were installed. She received additional 20mm anti-aircraft guns, expanded mess space and fire-suppression systems in her crew areas.

After a great deal of discussion and bureaucratic wrangling, the Admiralty and the U.S. Navy agreed that Victorious would retain her British air crews, but they would operate American aircraft using American procedures. New arrestor wires were fitted to the flight deck to handle the heavier American planes, and the British deck crew learned American take-off and landing procedures. All of the British crew received American-issued dungarees (for the enlisted men) and khakis (for the officers) to wear while operating in the Pacific.

Photo: HMS Victorious in port at Pearl Harbor, the British disruptive camouflage was to be overpainted with sea blue, the U.S. Navy Measure 11 specification.

New Grumman F4F-4 Wildcats and TBM Avengers replaced the Martlets, Fulmars and Albacores that had arrived at Norfolk with Victorious. The F4F-4 was identical to the Martlet IV, and no transition was necessary. The big Avenger was a different story; the ship’s aircraft cranes could not lift the planes when fully loaded, and the Avengers would only just barely fit on the ship’s aircraft elevators. The American liaison team suggested that Victorious fly only fighters, but Capt. L.D. Mackintosh demurred, not wishing to leave his ship without the anti-submarine capabilities of the Avenger. The Americans did not press the issue, and Victorious would operate both fighters and torpedo bombers.

British practice restricted an air group to only those aircraft that could be struck below into the hangar. Now under American command, Victorious added a deck park, increasing her capacity to from 42 planes (24 Martlets and 18 Albacores) to 52 (36 Martlets and 16 Avengers) but requiring that the deck crews learn complicated new procedures to move parked aircraft to allow take-offs and landings.

Together with the American destroyers Pringle, Bache and Converse, Victorious set out from Norfolk on 3 February, conducting flight exercises as she steamed southward. Her official call sign, “Robin,” became the unofficial name applied to her by American and eventually British sailors while she served the U.S. Navy. The Avengers proved just as troublesome in flight as on deck, with two fatal accidents claiming British aircrew.

Victorious barely fit through the Panama Canal, even after her crew removed some of her sponsons and aerials. She exchanged scrapes and gashes with the Gatun Locks, prompting the canal management to present a bill for damages to their facility before she entered the Pacific. Mackintosh scrawled “Lease Lend” across it and handed it back.

Victorious arrived at Pearl Harbor on 4 March, continuing to exercise her air and anti-aircraft crews during the voyage. More Avenger landings proved that the British arrestor system simply could not handle the huge brutes. The carrier went into dockyard hands again at Pearl Harbor to receive new arrestor wires, additional 40mm and 20mm anti-aircraft guns, and a coat of U.S. Navy battleship-gray paint outside and fireproof paint inside. Victorious also received a Coca-Cola dispenser and three ice-cream machines. “Ice cream is always available in large quantities,” Mackintosh reported to the Admiralty in a description of American practices, “and is much appreciated and is looked upon as essential.”

Mackintosh, one of the few British carrier commanders with flight experience - he had served as a Fleet Air Arm observer - insisted on rigorous training for his aircrew. Because the Americans often used cross-deck deployments where planes from one carrier would land on another and operate from there, Victorious had to use the same landing procedures as American ships. American deck crews used a different signaling system and confusion could prove deadly; for example, British and American batsmen (the crewman using brightly-colored paddles to wig-wag landing instructions to the incoming pilots) used the same signal for “Go Higher” and “You Are Too High,” respectively. A Royal Navy batsman had authority over the pilot during landing procedures and could tell him what to do including waving off a landing attempt; a U.S. Navy batsman merely relayed positioning information with final decisions in the pilot’s hands.

Victorious would operate one torpedo and three fighter squadrons in American service; while part of Home Fleet she had flown one torpedo and two fighter squadrons. The Avenger aircrews proved the most troublesome. Many of them had flown the Albacores of 832 Squadron, but were new to the Avenger. Others had been sent to the United States to train on the Avenger, but some of these men were not carrier-qualified when first assigned to Victorious. They had trained at Norfolk, but Mackintosh remained dissatisfied and asked for more time to practice.

Photo: Victorious and her air group at Noumean, New Caledonia. The Fleet Air Arm squadrons carried U.S. Navy markings for this deployment (Victorious deck hands added a small, unauthorized “Royal Navy” stencil).

For the next two months the aircrew trained in American methods, while the anti-aircraft gunners and damage control personnel underwent intensive training as well. Along with the battleship North Carolina, Victorious and her three destroyers left Pearl Harbor on 8 May, arriving in the war zone at Noumea on New Caledonia nine days later. The Royal Navy had entered the Solomons campaign.

Article was published in Avalanche Press and called South Pacific: USS Robin (Part One)

Link of interest: USS Robin: When the CNO Needed a Royal Navy Carrier – Part I and Part II

Ore this link about another What if HMS Victorious as a United States Navy carrier: The ship that never was (USS ROBIN)