Post by lordroel on Jul 14, 2017 17:18:03 GMT

What if: United States invasion of New Zealand & Australia

It sometimes seems that the ‘Special Relationship’ between Great Britain (and thus, until quite recently, by extension, Australia) and the United States has existed forever. Certainly since the dark days of 1942, through to ‘All the way with LBJ’, to the present deployment of the ADF in the continuing war against terrorism. However, this felicitous state of affairs hasn’t always been so. First though, to set the scene.

Background

IT REALLY ALL STARTED WITH THE BRITISH. At the beginning of the 20th century the United States was isolated from the powerful alliance systems of Europe that had dictated the affairs of that continent for centuries. Given this state of affairs Great Britain and, naturally, her Empire, had to be considered as potentially hostile. American planners were therefore obliged to consider the prospect of war between the two countries.

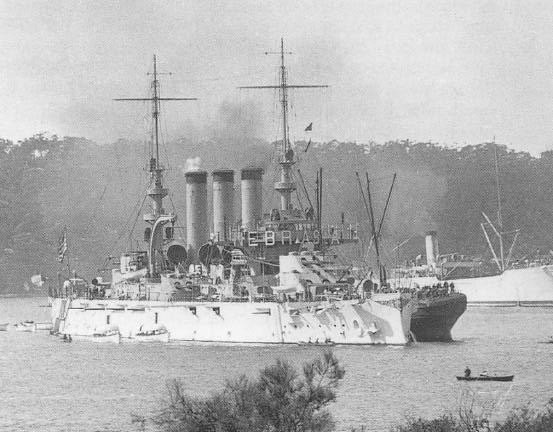

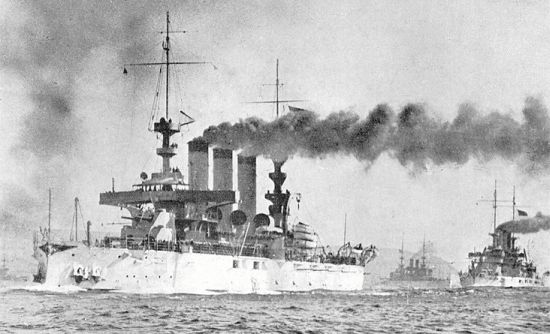

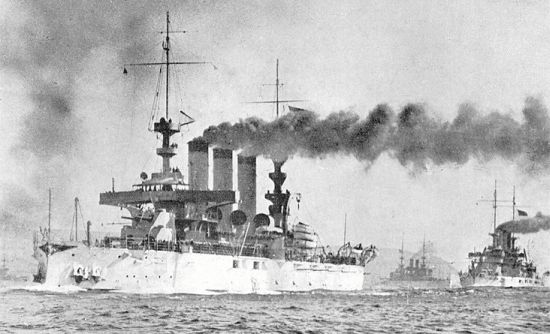

Picture of USS Nebraska, a unit of the Great White Fleet, visiting Sydney in 1908

In the United States system, colours were allocated to various nations, and the United Kingdom was assigned the code name RED. In turn Germany was BLACK, WHITE was France, ORANGE was Japan while the good guys, the US, were BLUE. (Subsets of the overall plan, certainly as far as the UK was concerned, were given ‘RED-ish colours such as SCARLET for Australia, GARNET for New Zealand, RUBY for India and CRIMSON for Canada.)

In war games conducted at the US National War College during the 1890s RED was always considered the aggressor, descending on the east coast of the continental US. Indeed, the British threat influenced the design of American capital ships, so that the United States Navy’s battle fleet was designed and built with a shallower-than-normal draught so that they could operate in shallow coastal waters in a defensive role. The fleet would therefore be at a disadvantage in operations in bluer, and thus deeper and more exposed, waters. So much for the Atlantic coast of the US.

As for the country’s Pacific coast, there doesn’t seem to have been any planning for its defence. Studies in the late 19th century of the defence of US possessions of the Philippines and the Hawaiian Islands concluded that they were indefensible. Elsewhere in the area, until the turn of the century there doesn’t seem to have been any attention paid to that ocean

Enter Great Britain: During the 1890s, although France and Russia were still considered to be her primary potential enemies, the rise of Germany was being viewed with increasing unease in Whitehall. One area in which Germany was expanding was in the Pacific, and so plans to deal with that threat had to be made. One aspect was a closer relationship with Japan, who had long been trying to interest Britain in an anti- Russian pact. Anglo-Japanese talks culminated in an Agreement in 1902. The negotiations were conducted in secret and without reference to a newly-Federated Australia, which was introducing an Immigration Restriction Bill, aimed primarily at the exclusion of Japanese from the country. The accord was developed further and by the conclusion of the Russo-Japanese war in 1905, which completely altered the balance of power in the Pacific, Japanese influence in the area was greatly expanded.

To make matters worse from the United States point of view, the conclusion of a more specific Anglo-Japanese Alliance in 1905 introduced a clause which bound the two signatories to come to the aid of each other should one of them become involved in a war with any other power.

Finally, anti-Japanese sentiments in California intensified during 1905, leading to serious rioting in San Francisco and other centres in 1907.

The situation was so threatening that the United States decided to assemble a fleet of battleships for ‘despatch to the Orient as soon as possible’.

Along the way the assemblage turned into a round the world cruise, a voyage that would be expanded later to include visits to New Zealand and Australia.

The adventures of this fleet, which came to be called ‘The Great White Fleet’ because of the colour of its hulls was under the command of Rear Admiral Charles S Sperry. He had formerly been President of the War College and thus could be considered to be thoroughly conversant with planning matters. An intelligence team led by Major Dion Williams USMC was embarked. After the fleet had visited Japan the admiral became ‘stubbornly confident that a row with Japan was imminent’. He therefore ordered that war plans be made for the capture of New Zealand and Australian ports. These plans were based on the premise that they were for use ‘in case of a war between the United Sates and Great Britain or a war involving those countries’. This implies that the planners had in mind a war with Japan in which Great Britain complied with the provisions of the Anglo-Japanese Alliance and was on Japan’s side.

Today this scenario may seem unlikely, but perceptions were different almost a century ago and in any case the admiral had spoken. So, despite overwhelming hospitality shown to the United States Navy in both Dominions, the visitor’s intelligence teams were busy beavering away to produce their plans.

The Auckland Attack Plan

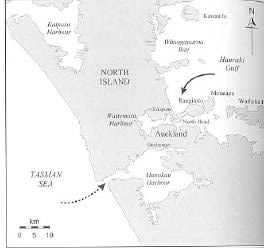

Capturing Auckland would provide the United States with an advanced base preparatory to attacking Sydney. Waitemata Harbour, Auckland’s principal harbour, was deemed ‘easy of defence’ but it was noted that there were no coastal artillery batteries, a deficiency ‘which was bitterly commented on by the British and New Zealand officers with whom our Intelligence officers talked at Auckland’. The report concluded that if ever the main harbour’s defences were improved Auckland would still have a weak point in the fact that ‘Manukau Harbor, on the western side of the island and directly opposite Auckland Harbor, offers a ready means of attacking the city from the rear’.

The planned position of a minefield to protect the approach to Waitemata Harbour was noted. The mines themselves were in short supply and those that were held were of an obsolete model.

The report listed the 1908 defence Order of Battle in considerable detail, noting that the bulk of the forces were volunteers, whose efficiency was ‘about up to the general average of the National Guardsmen in the United States, though not so well fitted out with field equipage and transportation’. Furthermore they were so widely scattered geographically that the entire force would never have to be dealt with at the same time.

So much for the Kiwis.

The Sydney Attack Plan

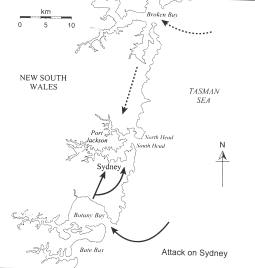

After the capture of Auckland, Sydney was next on the list. In a comprehensive report, which included a detailed eight-page summary of the defences of Port Jackson, Sydney was described as the principal goal: ‘A fortified base and coaling station for the British Navy, its attack and capture . . . would be a severe blow to the British in these waters’ and would afford the invader ‘the most desirable base for further operations both on land and at sea in and about Australia.’

There were, however, problems. Port Jackson was ‘comparatively strong and the entrance readily mined’. And, unlike New Zealand, there was a strong force available for its defence.

The American assessment concluded that a direct frontal assault would be difficult. It did, however, note that one of the principal disadvantages for the defenders was that ‘the city was practically directly on the sea coast, the center of the business portion of the city being but three sea miles from the open sea front’. This meant that ‘a fleet could lie off the entrance to the harbor and shell the whole city at effective ranges’. Shades of mid-1942.

Botany Bay, just ten miles south from the entrance to Port Jackson, attracted attention as a possible area for a flanking attack. Broken Bay was also considered but, according to the intelligence team, ‘such an attack would scarcely be advisable owing to the difficult ground lying between Broken Bay and Port Jackson’.

Laying these practicalities aside, the team looked at the broader picture and concluded that no operations with the capture of Sydney in mind should be undertaken until command of the sea had been assured. They concluded that ‘an examination of their defences (here they were referring to Sydney) and forces provided for these defences accentuate [sic] the firm reliance placed by all British subjects on the British Navy.’

They then considered the Royal Navy forces then on the Australia Station. These consisted of but three cruisers, only one of which, the large armoured cruiser HMS Powerful, had any military significance.

In a letter written at the time by a Lieutenant Commander who was the gunnery officer on board USS Connecticut the following assessment appeared.

‘These vessels were, with the exception of the Powerful, small and unimportant, and though frequent conversations were held with the officers, the comparative inattention given to Gunnery on the Australia Station rendered the information available of no value and of little interest. Among the British officers this is known as the Society Station and by tacit consent little work is done’.

Remarking on relations between British officers on the Station and the inhabitants of Australia and New Zealand the writer went on:

‘It may be stated that the feeling among the British officers on this Station and the Australians and New Zealanders is not the best, the latter in many cases regarding the officers as snobbish, while they in turn evince a feeling of suppressed disdain toward the general class of the inhabitants. This feature was very frequently remarked on, particularly by the middle classes . . . they often mentioned the democratic qualities in American officers in comparison with the aristocratic airs of the officers of the Royal Navy.’

THE SURREPTITIOUS WORK ON PLANNING for attack on Australian ports was conducted in an overwhelming atmosphere of hospitality by the Great White Fleet’s hosts. This validated the advice given to President Teddy Roosevelt by Admiral Sims when the Australian invitation had been received.

He wrote that the men of the Fleet would ‘barely escape with their lives from the hospitality of the people.’ This certainly proved to be the case in Sydney.

Finally dragging itself away from this reception, the Fleet moved on to Melbourne – to receive the same treatment.

Nothing dissuaded the intrepid intelligence planning teams though, and they put the time spent in the Victorian State capital to good account.

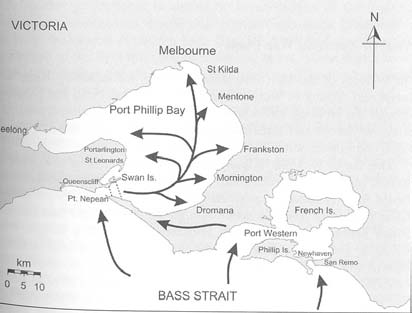

The Melbourne Attack Plan

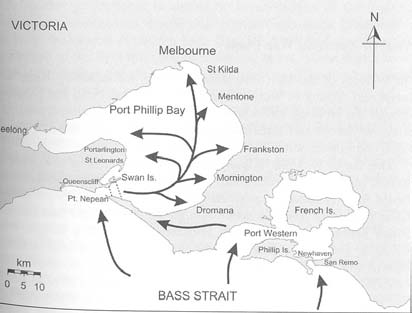

The team concluded that, if for some reason the occupation of Sydney was inappropriate, Port Phillip and Melbourne ‘. . . would be for many reasons a logical point of attack.’ As was the case with Sydney though, they stressed that command of the sea was a first requirement. No operations should take place against either port until command of the sea was sufficiently robust to enable a force of 25,000 soldiers to be moved across the Pacific. Also, as has already been mentioned, the Americans would first have to capture a port in New Zealand.

The entrance to Port Phillip presented problems. The entrance, at the Heads, followed a tortuous channel, with excellent sites for coastal defence batteries and good mining potential.

In the circumstances, a landing on the shores of Westernport (Port Western) seemed a good bet. If the entrance was mined (and there was a suspicion [erroneous] that it might be) then: ‘It would be best to land at San Remo and New Haven, and from there capture Phillip Island and thence clear up the road to Port Western, which would leave this road to the attack on the defences of Port Phillip open and also give a base from which to advance upon Melbourne.’

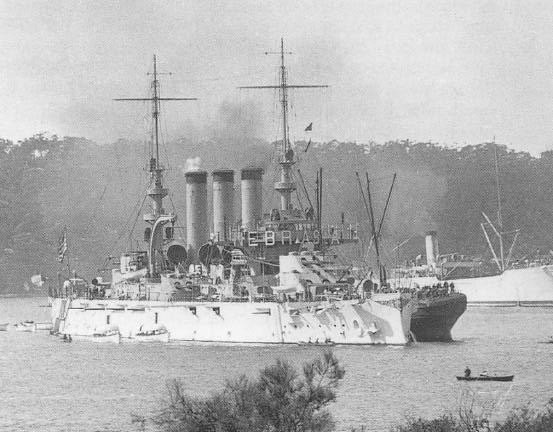

Picture showing Units of the Great White Fleet, 1908

The team prepared a comprehensive survey of the various defences of the area, noting that ‘. . . after the attacking force of ships is [once] inside Port Phillip the fire of the forts at the entrance (The Heads) would be of little or no avail against it.’

The greatest weakness to the defence of Melbourne, the assessment concluded, was that ‘the entrance to Port Western is not defended.’

Before moving to the final area to be examined by the intelligence team’s studies it is worth remarking that, when the ships sailed from Melbourne they left nearly 200 sailors behind. Half were recovered.

Western Australia Attack Plans

The depleted and socially exhausted fleet made for the west of the continent before continuing their voyage round the world. As in the eastern States, plans were drawn up for attacking King George Sound, Albany, as well as Fremantle and Perth. Though the problem was relatively simple due to the almost complete absence of fortifications or personnel to man them, these reports were extensive and thorough, comprising 32 and 35 pages respectively.

One of the reasons the planners gave for attacking western ports was to deal with the situation where the United States might approach the eastern part of the continent from either the Indian Ocean or through the Dutch East Indies, in which case they would form a forward base similar to Auckland.

Conclusions

Each of the plans briefly mentioned above was quite extensive. They examined and recorded in detail all aspects of the location covered: rail networks and connections; shipping lines and frequency of sailings; shipyard facilities; coal availability; layout of the cities; the nature of the sewage system; the state of electrification; hospitals, medical care; and details of the military forces available.

The teams’ war plans were, when finalised, first approved by the fleet commander-in-chief and then submitted to the Department of Navy. There they were stowed away, not, it would seem, seeing the light of day for the next nine decades. They were never apparently updated or revised.

So, what should we make of these plans?

Plans they may well have been, but they display some glaring weaknesses. A number of the more obvious are:

Nowhere is there any consideration of the Royal Navy. Even taking into account the disparaging (and largely justified) remarks about the ships on the Australia Station and their officers, elsewhere in the RN’s world it was an entirely different matter. By 1908, when the Great White Fleet visited Australia, ‘Jacky’ Fisher had been First Lord for long enough for his full-blown shake-up of the Royal Navy to be producing results. Any moves against Australia would have prompted an immediate reaction, primarily against America’s eastern seaboard, with dire results for the as-yet numerically inferior United States Navy.

The sheer size and complexity of any United States military undertaking in the south west Pacific seems to have been quite ignored, as does the now-familiar concept of a fleet train or underway replenishment (with coal it should be noted).

The risk of a Japanese involvement as a consequence of their commitment to come to the aid of the Royal Navy does not seem to have figured in the war plans.

Article was posted on Naval History Society of Australia and was called: American Plans for Invading New Zealand & Australia

It sometimes seems that the ‘Special Relationship’ between Great Britain (and thus, until quite recently, by extension, Australia) and the United States has existed forever. Certainly since the dark days of 1942, through to ‘All the way with LBJ’, to the present deployment of the ADF in the continuing war against terrorism. However, this felicitous state of affairs hasn’t always been so. First though, to set the scene.

Background

IT REALLY ALL STARTED WITH THE BRITISH. At the beginning of the 20th century the United States was isolated from the powerful alliance systems of Europe that had dictated the affairs of that continent for centuries. Given this state of affairs Great Britain and, naturally, her Empire, had to be considered as potentially hostile. American planners were therefore obliged to consider the prospect of war between the two countries.

Picture of USS Nebraska, a unit of the Great White Fleet, visiting Sydney in 1908

In the United States system, colours were allocated to various nations, and the United Kingdom was assigned the code name RED. In turn Germany was BLACK, WHITE was France, ORANGE was Japan while the good guys, the US, were BLUE. (Subsets of the overall plan, certainly as far as the UK was concerned, were given ‘RED-ish colours such as SCARLET for Australia, GARNET for New Zealand, RUBY for India and CRIMSON for Canada.)

In war games conducted at the US National War College during the 1890s RED was always considered the aggressor, descending on the east coast of the continental US. Indeed, the British threat influenced the design of American capital ships, so that the United States Navy’s battle fleet was designed and built with a shallower-than-normal draught so that they could operate in shallow coastal waters in a defensive role. The fleet would therefore be at a disadvantage in operations in bluer, and thus deeper and more exposed, waters. So much for the Atlantic coast of the US.

As for the country’s Pacific coast, there doesn’t seem to have been any planning for its defence. Studies in the late 19th century of the defence of US possessions of the Philippines and the Hawaiian Islands concluded that they were indefensible. Elsewhere in the area, until the turn of the century there doesn’t seem to have been any attention paid to that ocean

Enter Great Britain: During the 1890s, although France and Russia were still considered to be her primary potential enemies, the rise of Germany was being viewed with increasing unease in Whitehall. One area in which Germany was expanding was in the Pacific, and so plans to deal with that threat had to be made. One aspect was a closer relationship with Japan, who had long been trying to interest Britain in an anti- Russian pact. Anglo-Japanese talks culminated in an Agreement in 1902. The negotiations were conducted in secret and without reference to a newly-Federated Australia, which was introducing an Immigration Restriction Bill, aimed primarily at the exclusion of Japanese from the country. The accord was developed further and by the conclusion of the Russo-Japanese war in 1905, which completely altered the balance of power in the Pacific, Japanese influence in the area was greatly expanded.

To make matters worse from the United States point of view, the conclusion of a more specific Anglo-Japanese Alliance in 1905 introduced a clause which bound the two signatories to come to the aid of each other should one of them become involved in a war with any other power.

Finally, anti-Japanese sentiments in California intensified during 1905, leading to serious rioting in San Francisco and other centres in 1907.

The situation was so threatening that the United States decided to assemble a fleet of battleships for ‘despatch to the Orient as soon as possible’.

Along the way the assemblage turned into a round the world cruise, a voyage that would be expanded later to include visits to New Zealand and Australia.

The adventures of this fleet, which came to be called ‘The Great White Fleet’ because of the colour of its hulls was under the command of Rear Admiral Charles S Sperry. He had formerly been President of the War College and thus could be considered to be thoroughly conversant with planning matters. An intelligence team led by Major Dion Williams USMC was embarked. After the fleet had visited Japan the admiral became ‘stubbornly confident that a row with Japan was imminent’. He therefore ordered that war plans be made for the capture of New Zealand and Australian ports. These plans were based on the premise that they were for use ‘in case of a war between the United Sates and Great Britain or a war involving those countries’. This implies that the planners had in mind a war with Japan in which Great Britain complied with the provisions of the Anglo-Japanese Alliance and was on Japan’s side.

Today this scenario may seem unlikely, but perceptions were different almost a century ago and in any case the admiral had spoken. So, despite overwhelming hospitality shown to the United States Navy in both Dominions, the visitor’s intelligence teams were busy beavering away to produce their plans.

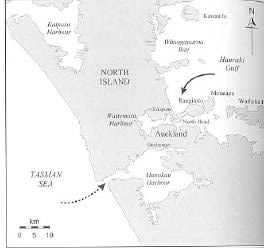

The Auckland Attack Plan

Capturing Auckland would provide the United States with an advanced base preparatory to attacking Sydney. Waitemata Harbour, Auckland’s principal harbour, was deemed ‘easy of defence’ but it was noted that there were no coastal artillery batteries, a deficiency ‘which was bitterly commented on by the British and New Zealand officers with whom our Intelligence officers talked at Auckland’. The report concluded that if ever the main harbour’s defences were improved Auckland would still have a weak point in the fact that ‘Manukau Harbor, on the western side of the island and directly opposite Auckland Harbor, offers a ready means of attacking the city from the rear’.

The planned position of a minefield to protect the approach to Waitemata Harbour was noted. The mines themselves were in short supply and those that were held were of an obsolete model.

The report listed the 1908 defence Order of Battle in considerable detail, noting that the bulk of the forces were volunteers, whose efficiency was ‘about up to the general average of the National Guardsmen in the United States, though not so well fitted out with field equipage and transportation’. Furthermore they were so widely scattered geographically that the entire force would never have to be dealt with at the same time.

So much for the Kiwis.

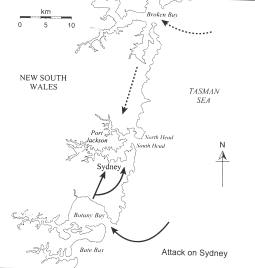

The Sydney Attack Plan

After the capture of Auckland, Sydney was next on the list. In a comprehensive report, which included a detailed eight-page summary of the defences of Port Jackson, Sydney was described as the principal goal: ‘A fortified base and coaling station for the British Navy, its attack and capture . . . would be a severe blow to the British in these waters’ and would afford the invader ‘the most desirable base for further operations both on land and at sea in and about Australia.’

There were, however, problems. Port Jackson was ‘comparatively strong and the entrance readily mined’. And, unlike New Zealand, there was a strong force available for its defence.

The American assessment concluded that a direct frontal assault would be difficult. It did, however, note that one of the principal disadvantages for the defenders was that ‘the city was practically directly on the sea coast, the center of the business portion of the city being but three sea miles from the open sea front’. This meant that ‘a fleet could lie off the entrance to the harbor and shell the whole city at effective ranges’. Shades of mid-1942.

Botany Bay, just ten miles south from the entrance to Port Jackson, attracted attention as a possible area for a flanking attack. Broken Bay was also considered but, according to the intelligence team, ‘such an attack would scarcely be advisable owing to the difficult ground lying between Broken Bay and Port Jackson’.

Laying these practicalities aside, the team looked at the broader picture and concluded that no operations with the capture of Sydney in mind should be undertaken until command of the sea had been assured. They concluded that ‘an examination of their defences (here they were referring to Sydney) and forces provided for these defences accentuate [sic] the firm reliance placed by all British subjects on the British Navy.’

They then considered the Royal Navy forces then on the Australia Station. These consisted of but three cruisers, only one of which, the large armoured cruiser HMS Powerful, had any military significance.

In a letter written at the time by a Lieutenant Commander who was the gunnery officer on board USS Connecticut the following assessment appeared.

‘These vessels were, with the exception of the Powerful, small and unimportant, and though frequent conversations were held with the officers, the comparative inattention given to Gunnery on the Australia Station rendered the information available of no value and of little interest. Among the British officers this is known as the Society Station and by tacit consent little work is done’.

Remarking on relations between British officers on the Station and the inhabitants of Australia and New Zealand the writer went on:

‘It may be stated that the feeling among the British officers on this Station and the Australians and New Zealanders is not the best, the latter in many cases regarding the officers as snobbish, while they in turn evince a feeling of suppressed disdain toward the general class of the inhabitants. This feature was very frequently remarked on, particularly by the middle classes . . . they often mentioned the democratic qualities in American officers in comparison with the aristocratic airs of the officers of the Royal Navy.’

THE SURREPTITIOUS WORK ON PLANNING for attack on Australian ports was conducted in an overwhelming atmosphere of hospitality by the Great White Fleet’s hosts. This validated the advice given to President Teddy Roosevelt by Admiral Sims when the Australian invitation had been received.

He wrote that the men of the Fleet would ‘barely escape with their lives from the hospitality of the people.’ This certainly proved to be the case in Sydney.

Finally dragging itself away from this reception, the Fleet moved on to Melbourne – to receive the same treatment.

Nothing dissuaded the intrepid intelligence planning teams though, and they put the time spent in the Victorian State capital to good account.

The Melbourne Attack Plan

The team concluded that, if for some reason the occupation of Sydney was inappropriate, Port Phillip and Melbourne ‘. . . would be for many reasons a logical point of attack.’ As was the case with Sydney though, they stressed that command of the sea was a first requirement. No operations should take place against either port until command of the sea was sufficiently robust to enable a force of 25,000 soldiers to be moved across the Pacific. Also, as has already been mentioned, the Americans would first have to capture a port in New Zealand.

The entrance to Port Phillip presented problems. The entrance, at the Heads, followed a tortuous channel, with excellent sites for coastal defence batteries and good mining potential.

In the circumstances, a landing on the shores of Westernport (Port Western) seemed a good bet. If the entrance was mined (and there was a suspicion [erroneous] that it might be) then: ‘It would be best to land at San Remo and New Haven, and from there capture Phillip Island and thence clear up the road to Port Western, which would leave this road to the attack on the defences of Port Phillip open and also give a base from which to advance upon Melbourne.’

Picture showing Units of the Great White Fleet, 1908

The team prepared a comprehensive survey of the various defences of the area, noting that ‘. . . after the attacking force of ships is [once] inside Port Phillip the fire of the forts at the entrance (The Heads) would be of little or no avail against it.’

The greatest weakness to the defence of Melbourne, the assessment concluded, was that ‘the entrance to Port Western is not defended.’

Before moving to the final area to be examined by the intelligence team’s studies it is worth remarking that, when the ships sailed from Melbourne they left nearly 200 sailors behind. Half were recovered.

Western Australia Attack Plans

The depleted and socially exhausted fleet made for the west of the continent before continuing their voyage round the world. As in the eastern States, plans were drawn up for attacking King George Sound, Albany, as well as Fremantle and Perth. Though the problem was relatively simple due to the almost complete absence of fortifications or personnel to man them, these reports were extensive and thorough, comprising 32 and 35 pages respectively.

One of the reasons the planners gave for attacking western ports was to deal with the situation where the United States might approach the eastern part of the continent from either the Indian Ocean or through the Dutch East Indies, in which case they would form a forward base similar to Auckland.

Conclusions

Each of the plans briefly mentioned above was quite extensive. They examined and recorded in detail all aspects of the location covered: rail networks and connections; shipping lines and frequency of sailings; shipyard facilities; coal availability; layout of the cities; the nature of the sewage system; the state of electrification; hospitals, medical care; and details of the military forces available.

The teams’ war plans were, when finalised, first approved by the fleet commander-in-chief and then submitted to the Department of Navy. There they were stowed away, not, it would seem, seeing the light of day for the next nine decades. They were never apparently updated or revised.

So, what should we make of these plans?

Plans they may well have been, but they display some glaring weaknesses. A number of the more obvious are:

Nowhere is there any consideration of the Royal Navy. Even taking into account the disparaging (and largely justified) remarks about the ships on the Australia Station and their officers, elsewhere in the RN’s world it was an entirely different matter. By 1908, when the Great White Fleet visited Australia, ‘Jacky’ Fisher had been First Lord for long enough for his full-blown shake-up of the Royal Navy to be producing results. Any moves against Australia would have prompted an immediate reaction, primarily against America’s eastern seaboard, with dire results for the as-yet numerically inferior United States Navy.

The sheer size and complexity of any United States military undertaking in the south west Pacific seems to have been quite ignored, as does the now-familiar concept of a fleet train or underway replenishment (with coal it should be noted).

The risk of a Japanese involvement as a consequence of their commitment to come to the aid of the Royal Navy does not seem to have figured in the war plans.

Article was posted on Naval History Society of Australia and was called: American Plans for Invading New Zealand & Australia