Post by lordroel on Jul 2, 2017 12:07:52 GMT

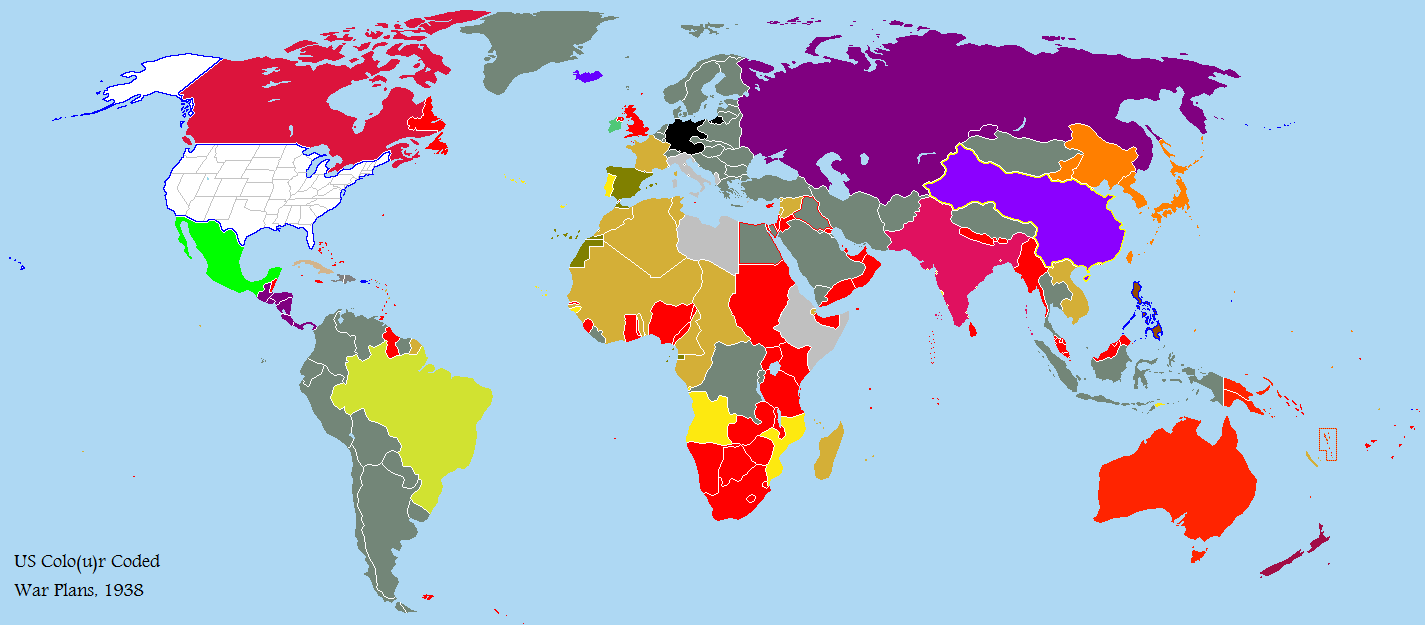

Article: United States color-coded war plans

The United States had a series of plans in place to deal with an array of potential adversaries. The primary war planning agencies of the period 1890-1939, which were the war colleges of the US Army and US Navy. In 1903 the Joint Army and Navy Board was established to attempt to make the two services work better together. Although initially the "Joint Board" had no independent war-planning authority, it did act as the final review board for war plans submitted to it by army and naval authorities. After the First World War, the Joint Board gained its own planning staff and was able to initiate plans itself. Economic constraints on the military in the inter-war period led the leaders of both services to try to coordinate their plans to a much greater extent than before the First World War. After World War I, the Joint Army and Navy Board (the predecessor of the Joint Chiefs of Staff) reviewed all the prewar plans to ensure they were consistent with the current state of affairs in the world.

List of War Plans

War Plan Black was a plan for war with Germany. The best-known version of Black was conceived as a contingency plan during World War I in case France fell and the Germans attempted to seize French possessions in the Caribbean, or launch an attack on the eastern seaboard.

War Plan Gray dealt with invading a Caribbean republic.

War Plan Brown dealt with an uprising in the Philippines.

War Plan Tan was for intervention in Cuba.

War Plan Red Plan for Great Britain.

War Plan Crimson was a sub variant of War Plan Red and which involved invading Canada.

War Plan Garnet was a sub variant of War Plan Red and which involved invading New Zealand

War Plan Scarlet was a sub variant of War Plan Red and which involved invading Australia.

War Plan Ruby was a sub variant of War Plan Red and which involved invading India.

War Plan Emerald was for intervention in Ireland in conjunction with War Plan Red.

War Plan Orange Plan for Japan

War Plan Yellow dealt with war in China - specifically, the defense of Beijing and relief of Shanghai during the Second Sino-Japanese War.

War Plan Green involved war with Mexico or what was known as "Mexican Domestic Intervention" in order to defeat rebel forces and establish a pro-American government. War Plan Green was officially canceled in 1946.

War Plan Indigo involved an occupation of Iceland. In 1941, while Denmark was under German occupation, the US actually did occupy Iceland, relieving British units during the Battle of the Atlantic.

War Plan Purple dealt with invading a South American republic.

War Plan Violet covered Latin America.

War Plan Gray involved a invasion of the Azores Islands in 1940–41.

War Plan Silver was for war with Italy.

War Plan Olive was for war with Spain.

War Plan Lemon was for war with Portugal.

War Plan Citron was for war with Brazil.

War Plan White dealt with a domestic uprising in the US, and later evolved to Operation Garden Plot, the general US military plan for civil disturbances and peaceful protests. Parts of War Plan White were used to deal with the Bonus Expeditionary Force in 1932. Communist insurgents were considered the most likely threat by the authors of War Plan White.

In addition there were combinations such as Red-Orange, which was necessitated by the Anglo-Japanese military alliance which expired in 1924.

Rainbow plans

The eighth and final change to WPL13 was made in March 1939. This change reflected the initial shift in U.S. strategic thinking from the Pacific to events in Europe and the Atlantic Ocean, away from offensive operations toward a concept of defensive operations and readiness. At the same time a new planning system replaced the colors adopted over thirty years before with the Rainbow Plans described briefly as follows:

Rainbow 1 (WPL42): Limited action in order to prevent a violation of the Monroe Doctrine as far south as 10 degrees south latitude. This plan was approved by the Secretaries of War and Navy on 14 August 1939.

Rainbow 2: Rainbow 1 in first priority followed by concerted action by the United States, Great Britain, and France against the Fascist powers. U.S. forces responsible solely for the Pacific.

Rainbow 3 (WPL44): Rainbow 1 in first priority followed by projecting American forces into the western Pacific.

RAINBOW 4 assumed United States Army forces would be sent to the southern part of South America, and a strategic defensive, as in RAINBOW 1, was to be maintained in the Pacific until the situation in the Atlantic permitted transfer of major naval forces for an offensive against Japan.

Rainbow 5 (WPL46): Rainbow 1 in first priority followed by U.S. armed forces into east Atlantic or Europe and Africa in concert with Great Britain and France. (Modified to conform to the course of the war in Europe during 1940 until December 1941.)

Planning for WPL13 appears to have continued during 1939 and into early 1940. Attempting to add realism, planners in September 1939 assumed that Japan would dominate the Asian coast and adjacent waters as far south as Indochina. They rejected a hypothesis that Japan already controlled the Netherlands East Indies and was poised to take over Singapore and the Philippines. The planners also considered a third alternative -- than Japan had not yet moved southward from Formosa -- since the central issue was at what point the United States would intervene. The planners rejected this alternative because they could not decide whether it would necessitate intervention and were not certain that the American people would support such preventive measures as early movement of the U.S. Fleet to the Philippines, to the East Indies, or to Singapore.

Rainbow 2 for 1939 described solely a naval war in which the United States had made no commitment to China. The plan concentrated on measures necessary to keep pressure on Japanese overseas lines of supply and communication. It did contain for the first time a specific COMINT-related task levied on the Naval Communications Service. The service was to intercept enemy communications and locate enemy units (using DF) and turn over the information to ONI for "dissemination as advisable." Although many concerned voices were raised over the inherent weaknesses of WPL13 and the Pacific war features of Rainbow 2, this is the last recorded activity in Pacific war planning until June 1941.

In April 1939 the strategists of the Joint Board concluded that, in the event of a threat in both oceans simultaneously, the United States should assume the defensive in the Pacific, retaining adequate forces based on Hawaii to guard the strategic triangle. Arguing further in a manner reminiscent of RED-ORANGE planning, the Joint Board planners declared that priority in a two-ocean war must go first to the defense of vital positions in the Western Hemisphere-the Panama Canal and the Caribbean area. From bases in that region, the US Fleet could operate in either ocean as the situation demanded.

The Joint Board in June 1939 laid down the guide lines for the development of new war plans, aptly designated RAINBOW to distinguish them from the color plans. There were to be five RAINBOW plans in all, each of them based on a different situation. Under RAINBOW 1, a strategic defensive was to be maintained in the Pacific, from behind the line Alaska-Hawaii-Panama, until developments in the Atlantic permitted concentration of the fleet in mid-Pacific for offensive action against Japan. Under RAINBOW 2, the United States would undertake immediate offensive operations across the Pacific to sustain the interests of democratic powers by the defeat of enemy forces. RAINBOW 4 assumed United States Army forces would be sent to the southern part of South America, and a strategic defensive, as in RAINBOW 1, was to be maintained in the Pacific until the situation in the Atlantic permitted transfer of major naval forces for an offensive against Japan. Under RAINBOW 5, there would be early projection of U.S. forces to the eastern Atlantic, and to either or both the African and European Continents; followed by offensive operations conducted to defeat of Germany and Italy. A strategic defensive was to be maintained in the Pacific until success against the European Axis Powers permitted transfer of major forces to the Pacific for an offensive against Japan.

In the spring of 1940, the nature of the war in Europe changed abruptly. Early in April 1940 German forces invaded Denmark and Norway and by the end of the month had occupied both countries. On 10 May 1940 he German campaign against France opened with the attack on the Netherlands and Belgium, and four days later German armor broke through the French defenses in the Ardennes. At the end of the month the British began the evacuation from Dunkerque, and on 10 June 1940 Italy declared war. A week later, the beaten and disorganized French Government sued for peace. With France defeated and England open to attack and invasion, the threat from the Atlantic looked real indeed.

In this crisis, American strategy underwent a critical review. Clearly, RAINBOW 2 and 3 with their orientation toward the far Pacific were scarcely applicable to a situation in which the main thrust seemed to lie in Europe. The defeat of France in June and the possibility that Great Britain might soon fall outweighed any danger that Japanese aggression could present to American security. Calling for an early decision from higher authority, the Army planners argued that since the United States could not fight everywhere - in the Far East, Europe, Africa, and South America - it should limit itself to a single course. Defense of the Western Hemisphere, they held, should constitute the main effort of American forces. In any case, the United States should not become involved with Japan and should concentrate on meeting the threat of Axis penetration into South America.

The Army's concern about America's ability to meet a possible threat from an Axis-dominated Europe in which the British and French Navies might be employed against the United States was shared by the Navy. As a result, the joint planners began work on RAINBOW 4, which only a month earlier had been accorded the lowest priority, and by the end of May 1940 had completed a plan. The situation envisaged now in RAINBOW 4 was a violation of the Monroe Doctrine by Germany and Italy coupled with armed aggression in Asia after the elimination of British and French forces and the termination of the war in Europe. Under these conditions, the United States was to limit its actions to defense of the entire Western Hemisphere, with American forces occupying British and French bases in the western Atlantic.

By June 1940 the critical point at issue in the discussions was the fate of the French Fleet and the future of Great Britain. The military wished to base their plans on the worst of all possible contingencies-that England, if not the British Empire, would be forced out of the war and that the French Fleet would fall to the Axis. If that fleet did fall into German hands, the planners recognized they would have to consider the question of whether to move the major portion of the U.S. Fleet to the Atlantic. Possession of the British and French Fleets would give the European Axis naval equality with the U.S. Fleet and make possible within six months hostile operations in the Western Hemisphere.

By October 1940 the British admitted frankly that their interests would be best served if the US Fleet remained in the Pacific. The US posture was that, until such time as the United States had engaged its full forces in war, the best course was to build up the defenses of the Western Hemisphere and stand ready to fight off a threat in either ocean. If forced into war with Japan, the United States would at the same time enter the war in the Atlantic and limit operations in the mid-Pacific and Far East so as to permit prompt movement to the Atlantic of forces fully adequate to conduct a major offensive in that ocean.

The Europe First strategy was finally agreed upon with Great Britain at the Arcadia Conference, which met from 24 December 1941 to 14 January 1942. President Roosevelt and Prime Minister Churchill met with their advisers in Washington (the ARCADIA Conference) to establish the bases of coalition strategy and concert immediate measures to meet the military crisis. Reaffirming the principle laid down in Anglo-American staff conversations in Washington ten months earlier, they agreed that the first and main effort must go into defeating Germany, the more formidable enemy. Japan's turn would come later.

Rainbow 2 was the final Pacific-first strategic plan. It was never adopted by the Joint Board or published. Beginning in early 1940, the entire focus of American strategy changed following Germany's easy victories in Norway and Denmark. The shift in focus was signaled by a letter from the joint Planning Committee to the Joint Board on 9 April 1940, recommending that planning begin immediately under Rainbow 5, leaving Rainbow 3 and 4 in skeletal form. With this letter, Pacific-first strategic thought and planning was virtually at an end. The fall of France in June 1940 and the subsequent Battle of Britain raised serious questions about the security of the United States itself, whether or not the British Isles would fall as France had, and the fate of the British Navy. Suddenly, the fate of England and control of the Atlantic Ocean were the most vital planning issues in American policy.

The brief but interesting evolution of Rainbow 5 from being one among equals to the preeminent U.S. war plan is also instructive. It not only involves the final stages of the other four plans, but its details, too, lend insight to the events of December 1941.

After the fall of France in June 1940, General George C. Marshall, Army Chief of Staff, and Admiral Harold R. Stark, Chief of Naval Operations, submitted to President Roosevelt a draft entitled "Bases for Immediate Decisions Concerning National Defense." As amended after the president's views were obtained, it became on 27 June 1940 a plan for national defense. Its six provisions were as follows:

Assumption of a defensive posture by the U.S.

Provision of support for the British Commonwealth and China.

Implementation of Rainbow 4 actions for defense of the hemisphere.

Cooperation with certain South American countries.

Undertaking of "progressive" mobilization including a draft and other measures to accelerate production of war material and training of personnel.

Beginning of preparations for the "almost inevitable conflict" with totalitarian powers.

Although planning for war with Japan was not extinct, the end was now near. On 25 September 1940, a memorandum prepared by Army planners for their boss, Major General George V. Strong, examined U.S. prospects in the event of a British defeat in the Atlantic in the context of the American commitment in the Pacific (i.e., Rainbow 3 vs Rainbow 4) and concluded that they were incompatible policies. Army planners went one step further and warned against a more active policy of pressure toward Japan. They recommended rapid U.S. rearmament, aid to Great Britain, refraining from antagonizing Japan, remaining on defensive in the Pacific, and finally, moving to ensure the security of the western Atlantic.

In a similar study two month later, Navy war planners under Captain Richmond K. Turner discovered that realistic Pacific operations under Rainbow 3 would be impossible if the naval detachment required under Rainbow 4 were transferred to the Atlantic. With the forces available, they reported, the U.S. Navy could operate in only one theater. This discovery led Admiral Stark to write his famous "Plan Dog" memorandum to Secretary Knox on 12 November 1940. The ideas contained in his memorandum had not changed significantly between June and November, although they did reflect some of General Strong's thoughts from September. His conclusion, however, was remarkable: the United States might "do little more in the Pacific than remain on a strict defensive."

Clearly, the first U.S. priority was to the British war effort and to prevent the war in Europe from spreading to the Western Hemisphere. Still it is startling to see the Chief of Naval Operations, in the fall of 1940, advocating a policy of avoiding even a limited war with Japan after over thirty years of planning for an unlimited offensive war. The only concession Stark would make was to leave the U.S. fleet at Pearl Harbor because of the U.S. diplomatic commitments in the Far East. His firmness in this purpose was to cost Admiral James O. Richardson, Commander in Chief, U.S. Fleet, his job.

In the year before the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor, American strategists developed a strategy that focused on “Germany first.” In the end, that was what occurred with the American war effort. But for much of 1942 and well into 1943, the United States deployed substantially greater forces to the Pacific than to Europe. This was in response both to political pressure from the American people and the rapidly deteriorating situation in the Pacific over the first six months of the war.

One could argue that the situation on the Eastern Front in summer 1942 appeared to be deteriorating even more rapidly than that in the Pacific, as German forces advanced toward Stalingrad and the Caucasus. Nevertheless, there was relatively little that American military power as it existed at the time could do to help the Soviets. American military planners at the urging of President Roosevelt did draw up tentative plans for a suicidal landing on the coast of France, should the Soviets appear to be collapsing but those plans did not have to be executed, because the Soviets were not in as desperate a situation in 1942 as they were suggesting at the time to their British and American “allies.”

Notwithstanding, in July 1942 President Franklin Roosevelt ordered U.S. commanders to execute major landings in fall 1942 against French North Africa to support British efforts in the Mediterranean. The army’s chief of staff, General George Marshall, argued vociferously that such a commitment would delay the strategic goal of achieving a major amphibious landing on the coast of northern France — the heart of the “Germany first” strategy — by at least a year. Marshall proved correct in his military estimate of the impact of Operation “Torch,” but what he missed was the political necessity of keeping the attention of the American people focused on the war against Germany, which held little interest for most of them, especially given the enormous anger that the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor had occasioned.

The United States had a series of plans in place to deal with an array of potential adversaries. The primary war planning agencies of the period 1890-1939, which were the war colleges of the US Army and US Navy. In 1903 the Joint Army and Navy Board was established to attempt to make the two services work better together. Although initially the "Joint Board" had no independent war-planning authority, it did act as the final review board for war plans submitted to it by army and naval authorities. After the First World War, the Joint Board gained its own planning staff and was able to initiate plans itself. Economic constraints on the military in the inter-war period led the leaders of both services to try to coordinate their plans to a much greater extent than before the First World War. After World War I, the Joint Army and Navy Board (the predecessor of the Joint Chiefs of Staff) reviewed all the prewar plans to ensure they were consistent with the current state of affairs in the world.

List of War Plans

War Plan Black was a plan for war with Germany. The best-known version of Black was conceived as a contingency plan during World War I in case France fell and the Germans attempted to seize French possessions in the Caribbean, or launch an attack on the eastern seaboard.

War Plan Gray dealt with invading a Caribbean republic.

War Plan Brown dealt with an uprising in the Philippines.

War Plan Tan was for intervention in Cuba.

War Plan Red Plan for Great Britain.

War Plan Crimson was a sub variant of War Plan Red and which involved invading Canada.

War Plan Garnet was a sub variant of War Plan Red and which involved invading New Zealand

War Plan Scarlet was a sub variant of War Plan Red and which involved invading Australia.

War Plan Ruby was a sub variant of War Plan Red and which involved invading India.

War Plan Emerald was for intervention in Ireland in conjunction with War Plan Red.

War Plan Orange Plan for Japan

War Plan Yellow dealt with war in China - specifically, the defense of Beijing and relief of Shanghai during the Second Sino-Japanese War.

War Plan Green involved war with Mexico or what was known as "Mexican Domestic Intervention" in order to defeat rebel forces and establish a pro-American government. War Plan Green was officially canceled in 1946.

War Plan Indigo involved an occupation of Iceland. In 1941, while Denmark was under German occupation, the US actually did occupy Iceland, relieving British units during the Battle of the Atlantic.

War Plan Purple dealt with invading a South American republic.

War Plan Violet covered Latin America.

War Plan Gray involved a invasion of the Azores Islands in 1940–41.

War Plan Silver was for war with Italy.

War Plan Olive was for war with Spain.

War Plan Lemon was for war with Portugal.

War Plan Citron was for war with Brazil.

War Plan White dealt with a domestic uprising in the US, and later evolved to Operation Garden Plot, the general US military plan for civil disturbances and peaceful protests. Parts of War Plan White were used to deal with the Bonus Expeditionary Force in 1932. Communist insurgents were considered the most likely threat by the authors of War Plan White.

In addition there were combinations such as Red-Orange, which was necessitated by the Anglo-Japanese military alliance which expired in 1924.

Rainbow plans

The eighth and final change to WPL13 was made in March 1939. This change reflected the initial shift in U.S. strategic thinking from the Pacific to events in Europe and the Atlantic Ocean, away from offensive operations toward a concept of defensive operations and readiness. At the same time a new planning system replaced the colors adopted over thirty years before with the Rainbow Plans described briefly as follows:

Rainbow 1 (WPL42): Limited action in order to prevent a violation of the Monroe Doctrine as far south as 10 degrees south latitude. This plan was approved by the Secretaries of War and Navy on 14 August 1939.

Rainbow 2: Rainbow 1 in first priority followed by concerted action by the United States, Great Britain, and France against the Fascist powers. U.S. forces responsible solely for the Pacific.

Rainbow 3 (WPL44): Rainbow 1 in first priority followed by projecting American forces into the western Pacific.

RAINBOW 4 assumed United States Army forces would be sent to the southern part of South America, and a strategic defensive, as in RAINBOW 1, was to be maintained in the Pacific until the situation in the Atlantic permitted transfer of major naval forces for an offensive against Japan.

Rainbow 5 (WPL46): Rainbow 1 in first priority followed by U.S. armed forces into east Atlantic or Europe and Africa in concert with Great Britain and France. (Modified to conform to the course of the war in Europe during 1940 until December 1941.)

Planning for WPL13 appears to have continued during 1939 and into early 1940. Attempting to add realism, planners in September 1939 assumed that Japan would dominate the Asian coast and adjacent waters as far south as Indochina. They rejected a hypothesis that Japan already controlled the Netherlands East Indies and was poised to take over Singapore and the Philippines. The planners also considered a third alternative -- than Japan had not yet moved southward from Formosa -- since the central issue was at what point the United States would intervene. The planners rejected this alternative because they could not decide whether it would necessitate intervention and were not certain that the American people would support such preventive measures as early movement of the U.S. Fleet to the Philippines, to the East Indies, or to Singapore.

Rainbow 2 for 1939 described solely a naval war in which the United States had made no commitment to China. The plan concentrated on measures necessary to keep pressure on Japanese overseas lines of supply and communication. It did contain for the first time a specific COMINT-related task levied on the Naval Communications Service. The service was to intercept enemy communications and locate enemy units (using DF) and turn over the information to ONI for "dissemination as advisable." Although many concerned voices were raised over the inherent weaknesses of WPL13 and the Pacific war features of Rainbow 2, this is the last recorded activity in Pacific war planning until June 1941.

In April 1939 the strategists of the Joint Board concluded that, in the event of a threat in both oceans simultaneously, the United States should assume the defensive in the Pacific, retaining adequate forces based on Hawaii to guard the strategic triangle. Arguing further in a manner reminiscent of RED-ORANGE planning, the Joint Board planners declared that priority in a two-ocean war must go first to the defense of vital positions in the Western Hemisphere-the Panama Canal and the Caribbean area. From bases in that region, the US Fleet could operate in either ocean as the situation demanded.

The Joint Board in June 1939 laid down the guide lines for the development of new war plans, aptly designated RAINBOW to distinguish them from the color plans. There were to be five RAINBOW plans in all, each of them based on a different situation. Under RAINBOW 1, a strategic defensive was to be maintained in the Pacific, from behind the line Alaska-Hawaii-Panama, until developments in the Atlantic permitted concentration of the fleet in mid-Pacific for offensive action against Japan. Under RAINBOW 2, the United States would undertake immediate offensive operations across the Pacific to sustain the interests of democratic powers by the defeat of enemy forces. RAINBOW 4 assumed United States Army forces would be sent to the southern part of South America, and a strategic defensive, as in RAINBOW 1, was to be maintained in the Pacific until the situation in the Atlantic permitted transfer of major naval forces for an offensive against Japan. Under RAINBOW 5, there would be early projection of U.S. forces to the eastern Atlantic, and to either or both the African and European Continents; followed by offensive operations conducted to defeat of Germany and Italy. A strategic defensive was to be maintained in the Pacific until success against the European Axis Powers permitted transfer of major forces to the Pacific for an offensive against Japan.

In the spring of 1940, the nature of the war in Europe changed abruptly. Early in April 1940 German forces invaded Denmark and Norway and by the end of the month had occupied both countries. On 10 May 1940 he German campaign against France opened with the attack on the Netherlands and Belgium, and four days later German armor broke through the French defenses in the Ardennes. At the end of the month the British began the evacuation from Dunkerque, and on 10 June 1940 Italy declared war. A week later, the beaten and disorganized French Government sued for peace. With France defeated and England open to attack and invasion, the threat from the Atlantic looked real indeed.

In this crisis, American strategy underwent a critical review. Clearly, RAINBOW 2 and 3 with their orientation toward the far Pacific were scarcely applicable to a situation in which the main thrust seemed to lie in Europe. The defeat of France in June and the possibility that Great Britain might soon fall outweighed any danger that Japanese aggression could present to American security. Calling for an early decision from higher authority, the Army planners argued that since the United States could not fight everywhere - in the Far East, Europe, Africa, and South America - it should limit itself to a single course. Defense of the Western Hemisphere, they held, should constitute the main effort of American forces. In any case, the United States should not become involved with Japan and should concentrate on meeting the threat of Axis penetration into South America.

The Army's concern about America's ability to meet a possible threat from an Axis-dominated Europe in which the British and French Navies might be employed against the United States was shared by the Navy. As a result, the joint planners began work on RAINBOW 4, which only a month earlier had been accorded the lowest priority, and by the end of May 1940 had completed a plan. The situation envisaged now in RAINBOW 4 was a violation of the Monroe Doctrine by Germany and Italy coupled with armed aggression in Asia after the elimination of British and French forces and the termination of the war in Europe. Under these conditions, the United States was to limit its actions to defense of the entire Western Hemisphere, with American forces occupying British and French bases in the western Atlantic.

By June 1940 the critical point at issue in the discussions was the fate of the French Fleet and the future of Great Britain. The military wished to base their plans on the worst of all possible contingencies-that England, if not the British Empire, would be forced out of the war and that the French Fleet would fall to the Axis. If that fleet did fall into German hands, the planners recognized they would have to consider the question of whether to move the major portion of the U.S. Fleet to the Atlantic. Possession of the British and French Fleets would give the European Axis naval equality with the U.S. Fleet and make possible within six months hostile operations in the Western Hemisphere.

By October 1940 the British admitted frankly that their interests would be best served if the US Fleet remained in the Pacific. The US posture was that, until such time as the United States had engaged its full forces in war, the best course was to build up the defenses of the Western Hemisphere and stand ready to fight off a threat in either ocean. If forced into war with Japan, the United States would at the same time enter the war in the Atlantic and limit operations in the mid-Pacific and Far East so as to permit prompt movement to the Atlantic of forces fully adequate to conduct a major offensive in that ocean.

The Europe First strategy was finally agreed upon with Great Britain at the Arcadia Conference, which met from 24 December 1941 to 14 January 1942. President Roosevelt and Prime Minister Churchill met with their advisers in Washington (the ARCADIA Conference) to establish the bases of coalition strategy and concert immediate measures to meet the military crisis. Reaffirming the principle laid down in Anglo-American staff conversations in Washington ten months earlier, they agreed that the first and main effort must go into defeating Germany, the more formidable enemy. Japan's turn would come later.

Rainbow 2 was the final Pacific-first strategic plan. It was never adopted by the Joint Board or published. Beginning in early 1940, the entire focus of American strategy changed following Germany's easy victories in Norway and Denmark. The shift in focus was signaled by a letter from the joint Planning Committee to the Joint Board on 9 April 1940, recommending that planning begin immediately under Rainbow 5, leaving Rainbow 3 and 4 in skeletal form. With this letter, Pacific-first strategic thought and planning was virtually at an end. The fall of France in June 1940 and the subsequent Battle of Britain raised serious questions about the security of the United States itself, whether or not the British Isles would fall as France had, and the fate of the British Navy. Suddenly, the fate of England and control of the Atlantic Ocean were the most vital planning issues in American policy.

The brief but interesting evolution of Rainbow 5 from being one among equals to the preeminent U.S. war plan is also instructive. It not only involves the final stages of the other four plans, but its details, too, lend insight to the events of December 1941.

After the fall of France in June 1940, General George C. Marshall, Army Chief of Staff, and Admiral Harold R. Stark, Chief of Naval Operations, submitted to President Roosevelt a draft entitled "Bases for Immediate Decisions Concerning National Defense." As amended after the president's views were obtained, it became on 27 June 1940 a plan for national defense. Its six provisions were as follows:

Assumption of a defensive posture by the U.S.

Provision of support for the British Commonwealth and China.

Implementation of Rainbow 4 actions for defense of the hemisphere.

Cooperation with certain South American countries.

Undertaking of "progressive" mobilization including a draft and other measures to accelerate production of war material and training of personnel.

Beginning of preparations for the "almost inevitable conflict" with totalitarian powers.

Although planning for war with Japan was not extinct, the end was now near. On 25 September 1940, a memorandum prepared by Army planners for their boss, Major General George V. Strong, examined U.S. prospects in the event of a British defeat in the Atlantic in the context of the American commitment in the Pacific (i.e., Rainbow 3 vs Rainbow 4) and concluded that they were incompatible policies. Army planners went one step further and warned against a more active policy of pressure toward Japan. They recommended rapid U.S. rearmament, aid to Great Britain, refraining from antagonizing Japan, remaining on defensive in the Pacific, and finally, moving to ensure the security of the western Atlantic.

In a similar study two month later, Navy war planners under Captain Richmond K. Turner discovered that realistic Pacific operations under Rainbow 3 would be impossible if the naval detachment required under Rainbow 4 were transferred to the Atlantic. With the forces available, they reported, the U.S. Navy could operate in only one theater. This discovery led Admiral Stark to write his famous "Plan Dog" memorandum to Secretary Knox on 12 November 1940. The ideas contained in his memorandum had not changed significantly between June and November, although they did reflect some of General Strong's thoughts from September. His conclusion, however, was remarkable: the United States might "do little more in the Pacific than remain on a strict defensive."

Clearly, the first U.S. priority was to the British war effort and to prevent the war in Europe from spreading to the Western Hemisphere. Still it is startling to see the Chief of Naval Operations, in the fall of 1940, advocating a policy of avoiding even a limited war with Japan after over thirty years of planning for an unlimited offensive war. The only concession Stark would make was to leave the U.S. fleet at Pearl Harbor because of the U.S. diplomatic commitments in the Far East. His firmness in this purpose was to cost Admiral James O. Richardson, Commander in Chief, U.S. Fleet, his job.

In the year before the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor, American strategists developed a strategy that focused on “Germany first.” In the end, that was what occurred with the American war effort. But for much of 1942 and well into 1943, the United States deployed substantially greater forces to the Pacific than to Europe. This was in response both to political pressure from the American people and the rapidly deteriorating situation in the Pacific over the first six months of the war.

One could argue that the situation on the Eastern Front in summer 1942 appeared to be deteriorating even more rapidly than that in the Pacific, as German forces advanced toward Stalingrad and the Caucasus. Nevertheless, there was relatively little that American military power as it existed at the time could do to help the Soviets. American military planners at the urging of President Roosevelt did draw up tentative plans for a suicidal landing on the coast of France, should the Soviets appear to be collapsing but those plans did not have to be executed, because the Soviets were not in as desperate a situation in 1942 as they were suggesting at the time to their British and American “allies.”

Notwithstanding, in July 1942 President Franklin Roosevelt ordered U.S. commanders to execute major landings in fall 1942 against French North Africa to support British efforts in the Mediterranean. The army’s chief of staff, General George Marshall, argued vociferously that such a commitment would delay the strategic goal of achieving a major amphibious landing on the coast of northern France — the heart of the “Germany first” strategy — by at least a year. Marshall proved correct in his military estimate of the impact of Operation “Torch,” but what he missed was the political necessity of keeping the attention of the American people focused on the war against Germany, which held little interest for most of them, especially given the enormous anger that the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor had occasioned.