Post by miletus12 on May 7, 2023 17:37:39 GMT

LETTER:

C/O United States Post Office / General Delivery

24 Beacon Street, Boston, MA

22 September 1888

Doctor Norman Oswald Bates DP

C/O The Athenaeum

107 Pall Mall

London, United Kingdom

My dear Norman:

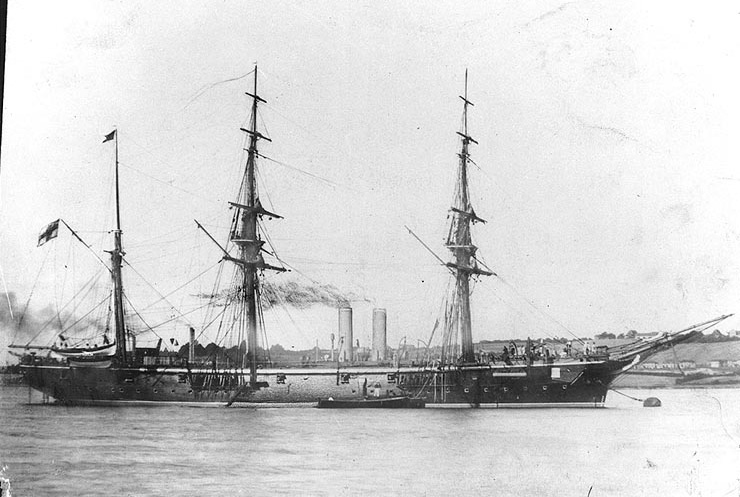

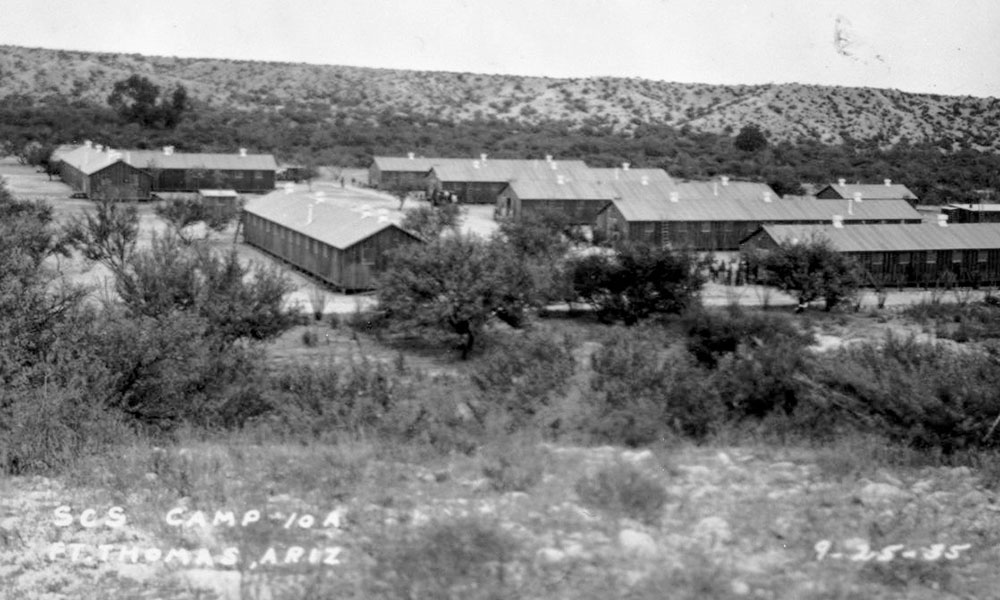

I have been a year in this benighted territory called Arizona. The inhabitants continually insist that I sit me upon a horse and conduct my travels and affairs from thereupon, when in a civilized milieu one would summon a carriage. But this is not London and it is certainly not India, where in my youth I was of more of the custom to ride mounted. That was when I officered Punjabis in the 15th Lancers (Cureton's Multanis). So I have some experience in the matters of a conversation I will relate to you, that I had with an American soldier, named William Fritch, as we rode a stage coach from Tombstone to Fort Thomas on the Gila River.

It was quite a trip and quite a revelation.

He was a black man and a sergeant, of about his mid-forties. He claimed that he enlisted in the American War of the Rebellion for the Union side in the year 1864 and served with the US 5th Cavalry (colored troops). He spoke some of his service in that war. His chief remarks of that piece of history in remembrance was that he learned the difference between a plow horse and a war horse, and between a stuffed shirt and a man. He seemed bitter about that part of his history, saying; “When you fight to prove that you are a man, with a man’s right to be free; it is one thing to fight an enemy who presumes that you are cattle and deserve to be so treated. It is another to fight alongside men who think exactly the same of you; who wear the same uniform you wear, and who purport to fight for the same cause as you.”

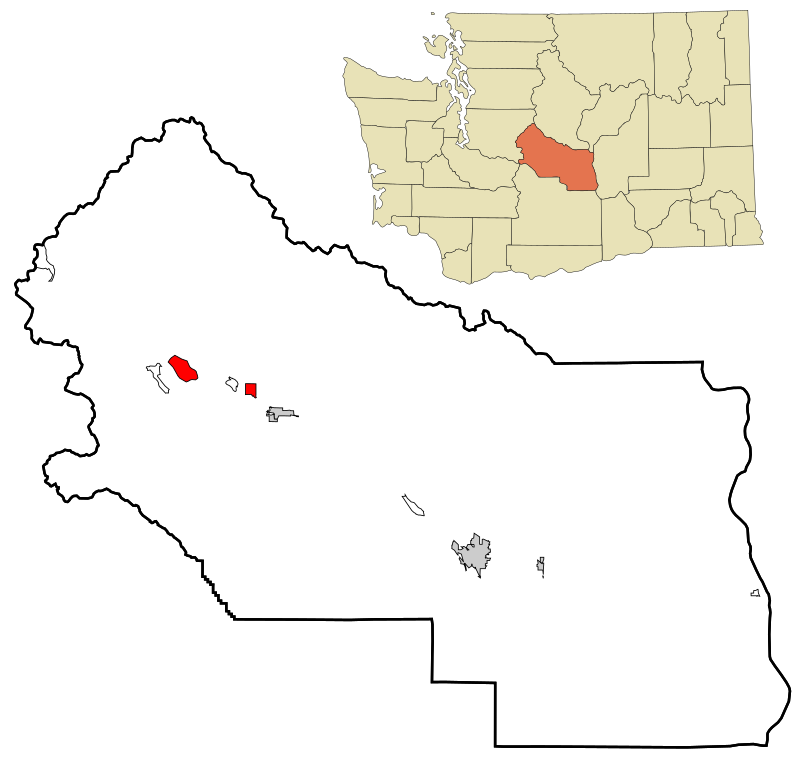

His recounts of the two Battles of Saltville, Virginia (Battles of Saltville, Virginia) seemed very like the raids the 15th Lancers conducted against the Afghans in my own war, although with much lesser glory or significant results. I made comment upon that fact, and further remarked that this territory of Arizona reminded me a little of the Northwest Frontier.

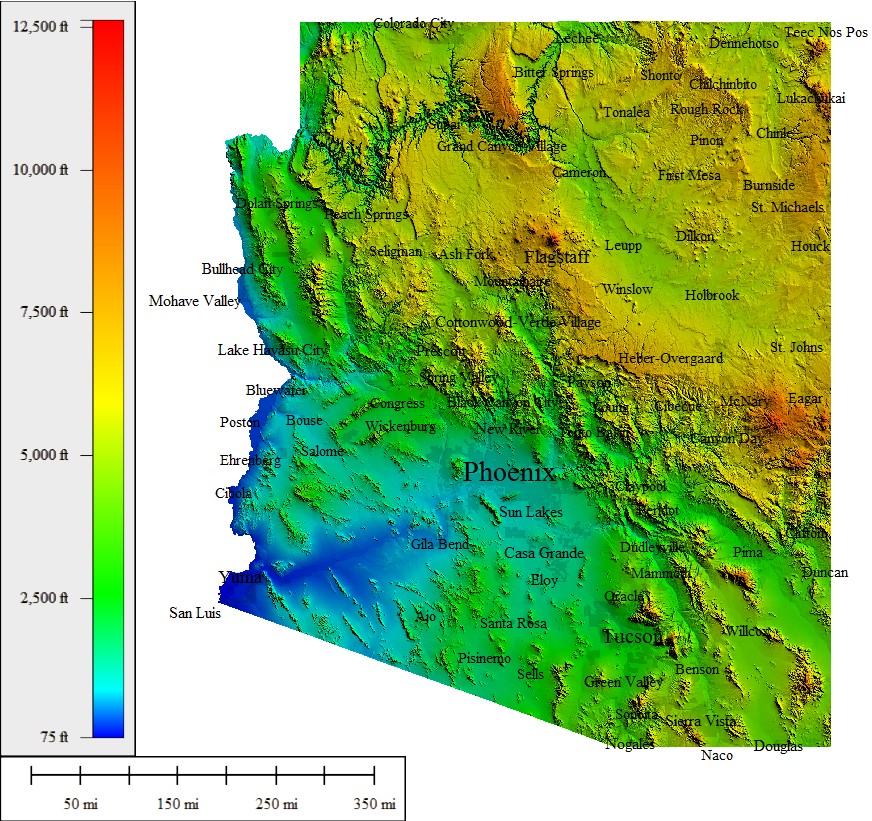

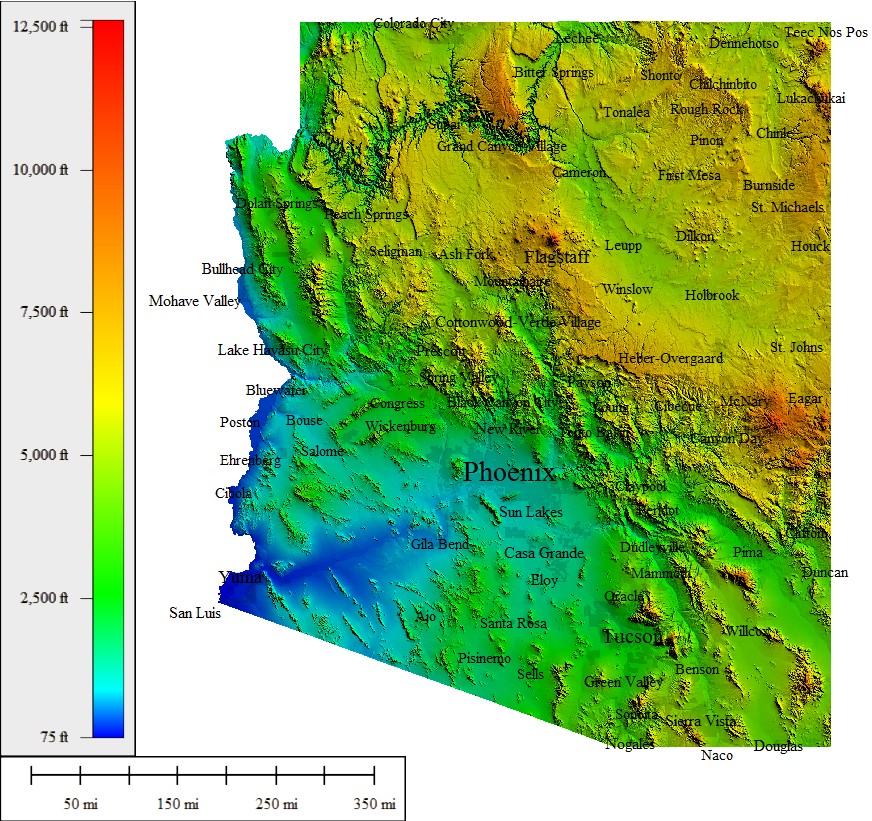

He then took me to school, by pointing out that Arizona was a richer country with watered rivers and minerals, with a paucity of people that was not true of the Northwest Frontier.

He further argued with me that with the mountains that bisected Arizona from the northeast plateau to the lowlands of the southwest, that the military geographic similarities were nothing alike. He said; “We have fewer troops than you had with our two regiments to patrol and police this territory; whereas you of the British Indian Army had 50,000 or more men invading a region; which though with twice the size of Arizona had fewer than 15,000 fighters armed and ready to oppose your aggressions.”

I rejoined that if I was an invader into Afghanistan, then what was he in Arizona in what used to be a part of Mexico?

He said; “What makes you think, that I am the invader, here? That I wear the American army uniform? That I try to keep the Mexicans on their side of the line and my people on our side of the line? That I try to make sure that the US mail contracted stage coaches get through? That I try to prevent the native peoples from being massacred by the bandits and so-called territorial militias? Or that I bring the law to bear; where there is none?”

I pointed to the fact that he was a mere sergeant.

He came back at me: “Don’t let the stripes fool you. I learned to read and write when I was twenty; so that I could read the regulations to make corporal. I learned to think for me when I was thirty to make sergeant. You don’t make sergeant in this American army without knowing that difference between what is reality and what is not, Wycliffe. Have you ever led a troop out on your own book, because there were no officers present who could do it better or even as well? I mean, have you ever done anything in your so-called military life without someone holding your hand and wiping your nose? I bet you never made it past Lieutenant.”

This last accusation was true. The military life and I were ill-suited, which was why I took up my present life of academia.

I was still quite insulted. I was about to stand up for myself, when he put his hand up; “Save your breath. You probably had a Sepoy sergeant who did your thinking and manhandling for you. Army to army, that is the way it works until you make captain as an officer. You have to grow up and mature into it. Believe what you want about yourself, Wycliffe. Just don’t lie about it to me, or pretend that you are me. You were never born a slave. You are not a career soldier. And you don’t have the right to judge me or what I do or why I actually do it, imperialist. ”

Needless to say, it was a most unpleasant coach trip after that conversation. I think the only time we spoke again, was when I asked him about Turkey Top.^1

He said: "Custer lost the big one at the Little Big Horn. Cibecue Creek was our Little One." He then fell silent for the next two days.

I tell you, Norman. That is the usual kind of reception I obtain from these Americans. I want to finish this business, and come home.

Your Servant and colleague;

Brandon Croyden Wycliffe, ESQ. OM FRS.

C/O United States Post Office / General Delivery

24 Beacon Street, Boston, MA

22 September 1888

Doctor Norman Oswald Bates DP

C/O The Athenaeum

107 Pall Mall

London, United Kingdom

My dear Norman:

I have been a year in this benighted territory called Arizona. The inhabitants continually insist that I sit me upon a horse and conduct my travels and affairs from thereupon, when in a civilized milieu one would summon a carriage. But this is not London and it is certainly not India, where in my youth I was of more of the custom to ride mounted. That was when I officered Punjabis in the 15th Lancers (Cureton's Multanis). So I have some experience in the matters of a conversation I will relate to you, that I had with an American soldier, named William Fritch, as we rode a stage coach from Tombstone to Fort Thomas on the Gila River.

It was quite a trip and quite a revelation.

He was a black man and a sergeant, of about his mid-forties. He claimed that he enlisted in the American War of the Rebellion for the Union side in the year 1864 and served with the US 5th Cavalry (colored troops). He spoke some of his service in that war. His chief remarks of that piece of history in remembrance was that he learned the difference between a plow horse and a war horse, and between a stuffed shirt and a man. He seemed bitter about that part of his history, saying; “When you fight to prove that you are a man, with a man’s right to be free; it is one thing to fight an enemy who presumes that you are cattle and deserve to be so treated. It is another to fight alongside men who think exactly the same of you; who wear the same uniform you wear, and who purport to fight for the same cause as you.”

His recounts of the two Battles of Saltville, Virginia (Battles of Saltville, Virginia) seemed very like the raids the 15th Lancers conducted against the Afghans in my own war, although with much lesser glory or significant results. I made comment upon that fact, and further remarked that this territory of Arizona reminded me a little of the Northwest Frontier.

He then took me to school, by pointing out that Arizona was a richer country with watered rivers and minerals, with a paucity of people that was not true of the Northwest Frontier.

He further argued with me that with the mountains that bisected Arizona from the northeast plateau to the lowlands of the southwest, that the military geographic similarities were nothing alike. He said; “We have fewer troops than you had with our two regiments to patrol and police this territory; whereas you of the British Indian Army had 50,000 or more men invading a region; which though with twice the size of Arizona had fewer than 15,000 fighters armed and ready to oppose your aggressions.”

I rejoined that if I was an invader into Afghanistan, then what was he in Arizona in what used to be a part of Mexico?

He said; “What makes you think, that I am the invader, here? That I wear the American army uniform? That I try to keep the Mexicans on their side of the line and my people on our side of the line? That I try to make sure that the US mail contracted stage coaches get through? That I try to prevent the native peoples from being massacred by the bandits and so-called territorial militias? Or that I bring the law to bear; where there is none?”

I pointed to the fact that he was a mere sergeant.

He came back at me: “Don’t let the stripes fool you. I learned to read and write when I was twenty; so that I could read the regulations to make corporal. I learned to think for me when I was thirty to make sergeant. You don’t make sergeant in this American army without knowing that difference between what is reality and what is not, Wycliffe. Have you ever led a troop out on your own book, because there were no officers present who could do it better or even as well? I mean, have you ever done anything in your so-called military life without someone holding your hand and wiping your nose? I bet you never made it past Lieutenant.”

This last accusation was true. The military life and I were ill-suited, which was why I took up my present life of academia.

I was still quite insulted. I was about to stand up for myself, when he put his hand up; “Save your breath. You probably had a Sepoy sergeant who did your thinking and manhandling for you. Army to army, that is the way it works until you make captain as an officer. You have to grow up and mature into it. Believe what you want about yourself, Wycliffe. Just don’t lie about it to me, or pretend that you are me. You were never born a slave. You are not a career soldier. And you don’t have the right to judge me or what I do or why I actually do it, imperialist. ”

Needless to say, it was a most unpleasant coach trip after that conversation. I think the only time we spoke again, was when I asked him about Turkey Top.^1

He said: "Custer lost the big one at the Little Big Horn. Cibecue Creek was our Little One." He then fell silent for the next two days.

I tell you, Norman. That is the usual kind of reception I obtain from these Americans. I want to finish this business, and come home.

Your Servant and colleague;

Brandon Croyden Wycliffe, ESQ. OM FRS.

^1 The Battle of Cibecue Creek & the Tragedy of Nockaydelklinne

By Joseph A. Williams

Flamed by rising tensions on Apache reservations, the Battle of Cibecue Creek was the U.S. Army’s worst military loss in the infamous Apache Wars of Arizona.

The Apache are one of the most famous tribes of the American Southwest and best known for their struggle to retain independence under the leadership of Geronimo. Yet Geronimo’s struggle, from 1876 to 1886, would probably have been far shorter were it not for the murder of a famous medicine man at Cibecue Creek on April 30, 1881.

The engagement, usually called the Battle of Cibecue Creek, is one of the sparks that escalated the Apache Wars and gave new strength to Apache resistance, and was eventually followed by the Battle of Big Dry Wash.

The Battle of Cibecue Creek had been coming for a long time. By the 1880s, the Apache had been steadily falling under the yoke of white settlers who had, as detailed by the author John R. Welch in the journal Kiva, been pushing into the Southwest.

The Apaches had been remarkably resilient in the face of European imperialism. For two and half centuries they successfully resisted colonization efforts by Spain and Mexico. However, American settlers proved a different matter and various Apache bands soon fell under the jurisdiction of the U.S. Army.

While some Apaches, notably the Chiricahua under Geronimo, resisted white encroachment, many did not. Over the years, various Apache bands maintained friendly alliances with the Americans and many enlisted into the army as scouts.

Federal heavy-handedness led to Apache unrest

The Apache are not a homogenous group, being a collection of various bands that have shared language and culture. Ironically, the name Apache comes from the Pueblo who called them Apachu, meaning “enemy.”

The Apache call themselves a variety of terms which mean the “People.” Ethnographers have difficulty in classifying the various Apache groups since there is much overlap in their historic movements.

Regardless, aside from a shared identity all the Apache were subject to the same heavy-handed policies from Washington, D.C. Families along the Cibecue Creek of the White Mountain Apache were forcibly relocated in 1877 to San Carlos to live in squalid conditions under a concentration policy. They were allowed to return to Cibecue in a few years, but the aftertaste must have been bitter, indeed.

To make matters worse, the Federal government was increasingly reducing the size of Apache reservations. This, coupled with corruption among federal agents, made the situation highly volatile. More Apache warriors began to turn to raiding in order to provide for their families. Still others turned to spiritual solace.

The Preaching of Nockaydelklinne

Among the White Mountain Apache was a medicine man and chief called Nockaydelklinne (there are also a variety of other spellings to the name), who lived along the Cibecue.

The journal Kiva traces his history: he studied at the Santa Fe Indian School, where he was probably influenced by Christian religious ideas of resurrection. He also visited President Ulysses S. Grant probably in 1872 or 1873 on a peace mission.

According to author Lori Davisson in the Journal of Arizona History, when the U.S. Army started recruiting Apache scouts in 1872, he enlisted under the presumed name of Bobby, and was described as mild-tempered.

He was also slightly built, standing at 5’6″ and 125 pounds. As a chief, he was reported as being open-handed and offered friendship toward the Americans. However, he had witnessed his people being forced off their lands, killed, and degraded. The Apaches were descending into a violent culture.

Nockaydelklinne became a spiritualist and spirit singer. He began to teach a new religion called na’ilde‘, which literally means “return from the dead.” The new type of religion unified traditional Apache healing practices with resurrection beliefs.

His growing following would sing, dance, and pray for the resurrection of dead chiefs. As described by The American Museum of Natural History, the dance was a kind of “Wheel Dance:”

The performers were arranged like the spokes of a wheel, all facing inward, Nakai’doklin’ni occupying the center or hub portion around which the whirling backward-and-forward, fanatical participants danced, as he sprinkled them with cattail-flag pollen and prayed over them to his gods.”

The medicine man claimed to have resurrected two chiefs and said that a divine miracle would destroy the white man. In fact, when other tribes came to have him use his divine powers to resurrect lost chiefs, he claimed that he could not do so until the white man was removed.

The medicine man was sometimes referred to as the Prophet.

The Medicine Man is Arrested

Some version of this story came to the ears of Indian Agent Joseph C. Tiffany and Colonel Eugene Asa Carr at Fort Apache.

This may have been triggered by numerous Apache scouts taking leave to attend Nockaydelklinne’s ceremonies. Perhaps to placate the whites, Nockaydelklinne performed the dance in front of them in July 1881. If anything, Tiffany must have grown more alarmed since on August 15, he telegraphed Carr telling him that the medicine man should be “arrested or killed or both.”

Shortly after, Carr received orders from his commander, General Wilcox, to arrest the medicine man. The U.S. Army tried to get the spirit singer to come in of his own accord, but he resisted claiming that he was not a leader and simply teaching what others wanted to learn.

He refused to go.

On the morning of August 29, Carr prepared to leave Fort Apache and journey the 40 miles to the medicine man’s encampment to arrest him. He went with 117 men, including 23 Apache scouts.

There was debate between Carr and his officers: could the Apache scouts be trusted? Carr decided that they should go. He later reported, as quoted in Apache Nightmare:

Carr arrived at the medicine man’s camp that same afternoon.

The Arrest of Nockaydelklinne

After Carr’s arrival on August 30, 1881, he entered Nockaydelklinne’s wickiup and told the medicine man he needed to stop the dances and come to Fort Apache. Then accounts of what happened diverge.

Most early histories of Cibecue Creek used the perspectives and accounts of the U.S. Army and American citizens. However, since these early 20th century accounts, Apache narratives have been captured and published, which provide stark perspectives.

Army accounts state that at first Nockaydelklinne was reluctant to leave and said that he would come if Carr withdrew. Carr refused but the medicine man was placated by the chief Apache scout named Mose.

Carr also reported that he told Nockaydelklinne that no harm would come to him if he did not resist. Carr also reported warning him that if anybody attempted to rescue him, he would be killed. Nockaydelklinne smiled and said nobody would try to rescue him.

This account is at odds with the account of Tom Friday, who was the son of the Apache scout Dead Shot. In Friday’s account, taken years later, it was Dead Shot, not Mose, who was sent to the medicine man’s encampment and it was Captain Edmund Hentig, not Carr who spoke with Nockaydelklinne. He also detailed how Hentig had barged into the lodging uninvited and dragged off the medicine man by the hair.

Regardless of the means by which the medicine man was arrested, the Apache scouts with the army were indeed conflicted. Many of them were followers of the Prophet and thought he was being arrested for no reason.

The Battle of Cibecue Creek

The medicine man, some of his family, and the soldiers began to head toward Fort Apache following the Cibecue Creek downstream. Apaches followed.

One American soldier wrote:

Due to the late hour, Carr ordered a halt to encamp for the night near a low hill by Cibecue Creek. Meanwhile, their encampment became ringed by Apache warriors. At this point, Captain Edmund Hentig shouted at the Apaches in their own language to go away.

The Apache scout Dead Shot complained that the scouts were encamped in a place with too many anthills. Permission was then given for the scouts to move closer to the other Apaches. This was done and according to the army’s account, Dead Shot gave a war-whup and the Apache scouts starting firing into the soldiers.

In army accounts it seemed to be a prearranged signal to start a treasonous mutiny.

In Tom Friday’s account, however, the fight started when Nockaydelklinne’s brother tried to retrieve the medicine man. The commanding army officer — presumably Carr or Hentig — called him a “very bad name” and ordered him to be shot.

This was done and the Battle of Cibecue Creek commenced. In the initial volley, Captain Hentig was killed.

The full truth of the matter may never be known. Tom Friday’s account, taken decades after the fight, may be questionable not only for its age, but also from Friday’s desire to protect the reputation of his father.

It seems that the army account is more likely to be correct on details, though that too may be questionable because of its natural bias toward the whites.

Good Will Toward Men

The Battle of Cibecue Creek was chaotic, with Apaches fortified on the low hill on the west side of the creek shooting at the army encampment on the east side. In the first few minutes of the fight, the handcuffed Nockaydelklinne fell to the ground and while attempting to crawl away from battle, a sergeant shot him in the legs before a trumpeter named William O. Benites fired a round through the medicine man’s neck with his revolver.

When the medicine man’s son saw this, he rushed in on a horse but was killed. Nockaydelklinne’s wife then grabbed a revolver and tried to exact revenge on her husband’s murderers. She was also quickly slain.

As the fight wore down that afternoon, a sergeant named John A. Smith saw that Nockaydelklinne was still alive. According to Apache accounts, he hewed the medicine man’s head off with a hatchet.

Smith then examined a medal that belonged to the medicine man. It was from President Grant. On one side it read “Let us have peace.” On the other it read, “On earth peace, good will toward men.”

Fighting stopped in the evening and the army buried its dead.

In the end, six privates and Captain Hentig were killed, as were 18 Apaches. Around midnight, Carr withdrew the army to Fort Apache, where they arrived on August 31.

Aftermath of the Battle of Cibecue Creek

In the aftermath of the battle, fighting continued.

On September 1, Apaches attacked Fort Apache with scattered gunfire, and nine soldiers were killed along Turkey Creek. Meanwhile, Apache families fled the area, sensing that violence was going to escalate.

Other Apache warriors and families who had been loyal to the army abandoned the fort and fled. It would be months before the Apache refugees would return to the reservation.

As for the Apache scouts who turned on the army at Cibecue Creek, five were arrested and brought before a military tribunal. Two were sentenced to Alcatraz but were paroled in 1884.

It was thought that many of the Apache scouts had just been swept up in the mutiny. The other three, which included Dead Shot, were executed by hanging on March 3, 1882. Before their deaths, all three proclaimed innocence and Dead Shot tried to escape.

Cibecue Creek is remarkable in being the worst military loss of the U.S. Army in Arizona’s history. It is also the only time that Apache scouts mutinied in their service to the army. The fight marks an escalation in the Apache Wars which led to a lingering insurgency that didn’t end until the capture of Geronimo in 1886.

By Joseph A. Williams

Flamed by rising tensions on Apache reservations, the Battle of Cibecue Creek was the U.S. Army’s worst military loss in the infamous Apache Wars of Arizona.

The Apache are one of the most famous tribes of the American Southwest and best known for their struggle to retain independence under the leadership of Geronimo. Yet Geronimo’s struggle, from 1876 to 1886, would probably have been far shorter were it not for the murder of a famous medicine man at Cibecue Creek on April 30, 1881.

The engagement, usually called the Battle of Cibecue Creek, is one of the sparks that escalated the Apache Wars and gave new strength to Apache resistance, and was eventually followed by the Battle of Big Dry Wash.

The Battle of Cibecue Creek had been coming for a long time. By the 1880s, the Apache had been steadily falling under the yoke of white settlers who had, as detailed by the author John R. Welch in the journal Kiva, been pushing into the Southwest.

The Apaches had been remarkably resilient in the face of European imperialism. For two and half centuries they successfully resisted colonization efforts by Spain and Mexico. However, American settlers proved a different matter and various Apache bands soon fell under the jurisdiction of the U.S. Army.

While some Apaches, notably the Chiricahua under Geronimo, resisted white encroachment, many did not. Over the years, various Apache bands maintained friendly alliances with the Americans and many enlisted into the army as scouts.

Federal heavy-handedness led to Apache unrest

The Apache are not a homogenous group, being a collection of various bands that have shared language and culture. Ironically, the name Apache comes from the Pueblo who called them Apachu, meaning “enemy.”

The Apache call themselves a variety of terms which mean the “People.” Ethnographers have difficulty in classifying the various Apache groups since there is much overlap in their historic movements.

Regardless, aside from a shared identity all the Apache were subject to the same heavy-handed policies from Washington, D.C. Families along the Cibecue Creek of the White Mountain Apache were forcibly relocated in 1877 to San Carlos to live in squalid conditions under a concentration policy. They were allowed to return to Cibecue in a few years, but the aftertaste must have been bitter, indeed.

To make matters worse, the Federal government was increasingly reducing the size of Apache reservations. This, coupled with corruption among federal agents, made the situation highly volatile. More Apache warriors began to turn to raiding in order to provide for their families. Still others turned to spiritual solace.

The Preaching of Nockaydelklinne

Among the White Mountain Apache was a medicine man and chief called Nockaydelklinne (there are also a variety of other spellings to the name), who lived along the Cibecue.

The journal Kiva traces his history: he studied at the Santa Fe Indian School, where he was probably influenced by Christian religious ideas of resurrection. He also visited President Ulysses S. Grant probably in 1872 or 1873 on a peace mission.

According to author Lori Davisson in the Journal of Arizona History, when the U.S. Army started recruiting Apache scouts in 1872, he enlisted under the presumed name of Bobby, and was described as mild-tempered.

He was also slightly built, standing at 5’6″ and 125 pounds. As a chief, he was reported as being open-handed and offered friendship toward the Americans. However, he had witnessed his people being forced off their lands, killed, and degraded. The Apaches were descending into a violent culture.

Nockaydelklinne became a spiritualist and spirit singer. He began to teach a new religion called na’ilde‘, which literally means “return from the dead.” The new type of religion unified traditional Apache healing practices with resurrection beliefs.

His growing following would sing, dance, and pray for the resurrection of dead chiefs. As described by The American Museum of Natural History, the dance was a kind of “Wheel Dance:”

The performers were arranged like the spokes of a wheel, all facing inward, Nakai’doklin’ni occupying the center or hub portion around which the whirling backward-and-forward, fanatical participants danced, as he sprinkled them with cattail-flag pollen and prayed over them to his gods.”

The medicine man claimed to have resurrected two chiefs and said that a divine miracle would destroy the white man. In fact, when other tribes came to have him use his divine powers to resurrect lost chiefs, he claimed that he could not do so until the white man was removed.

The medicine man was sometimes referred to as the Prophet.

The Medicine Man is Arrested

Some version of this story came to the ears of Indian Agent Joseph C. Tiffany and Colonel Eugene Asa Carr at Fort Apache.

This may have been triggered by numerous Apache scouts taking leave to attend Nockaydelklinne’s ceremonies. Perhaps to placate the whites, Nockaydelklinne performed the dance in front of them in July 1881. If anything, Tiffany must have grown more alarmed since on August 15, he telegraphed Carr telling him that the medicine man should be “arrested or killed or both.”

Shortly after, Carr received orders from his commander, General Wilcox, to arrest the medicine man. The U.S. Army tried to get the spirit singer to come in of his own accord, but he resisted claiming that he was not a leader and simply teaching what others wanted to learn.

He refused to go.

On the morning of August 29, Carr prepared to leave Fort Apache and journey the 40 miles to the medicine man’s encampment to arrest him. He went with 117 men, including 23 Apache scouts.

There was debate between Carr and his officers: could the Apache scouts be trusted? Carr decided that they should go. He later reported, as quoted in Apache Nightmare:

"I had to take my chances. They were enlisted men of my command, for duty; and I could not have found the medicine man without them. I deemed it better also if they should prove unfaithful it should not occur at the post.”

The Arrest of Nockaydelklinne

After Carr’s arrival on August 30, 1881, he entered Nockaydelklinne’s wickiup and told the medicine man he needed to stop the dances and come to Fort Apache. Then accounts of what happened diverge.

Most early histories of Cibecue Creek used the perspectives and accounts of the U.S. Army and American citizens. However, since these early 20th century accounts, Apache narratives have been captured and published, which provide stark perspectives.

Army accounts state that at first Nockaydelklinne was reluctant to leave and said that he would come if Carr withdrew. Carr refused but the medicine man was placated by the chief Apache scout named Mose.

Carr also reported that he told Nockaydelklinne that no harm would come to him if he did not resist. Carr also reported warning him that if anybody attempted to rescue him, he would be killed. Nockaydelklinne smiled and said nobody would try to rescue him.

This account is at odds with the account of Tom Friday, who was the son of the Apache scout Dead Shot. In Friday’s account, taken years later, it was Dead Shot, not Mose, who was sent to the medicine man’s encampment and it was Captain Edmund Hentig, not Carr who spoke with Nockaydelklinne. He also detailed how Hentig had barged into the lodging uninvited and dragged off the medicine man by the hair.

Regardless of the means by which the medicine man was arrested, the Apache scouts with the army were indeed conflicted. Many of them were followers of the Prophet and thought he was being arrested for no reason.

The Battle of Cibecue Creek

The medicine man, some of his family, and the soldiers began to head toward Fort Apache following the Cibecue Creek downstream. Apaches followed.

One American soldier wrote:

There was a rustling among the crowd of watching Indians that reminded me of the buzzing of a rattlesnake aroused. The Medicine Man’s wife ran ahead of him. She moved with a queer dance step and as she swayed she scattered the sacred meal about her.”

The Apache scout Dead Shot complained that the scouts were encamped in a place with too many anthills. Permission was then given for the scouts to move closer to the other Apaches. This was done and according to the army’s account, Dead Shot gave a war-whup and the Apache scouts starting firing into the soldiers.

In army accounts it seemed to be a prearranged signal to start a treasonous mutiny.

In Tom Friday’s account, however, the fight started when Nockaydelklinne’s brother tried to retrieve the medicine man. The commanding army officer — presumably Carr or Hentig — called him a “very bad name” and ordered him to be shot.

This was done and the Battle of Cibecue Creek commenced. In the initial volley, Captain Hentig was killed.

The full truth of the matter may never be known. Tom Friday’s account, taken decades after the fight, may be questionable not only for its age, but also from Friday’s desire to protect the reputation of his father.

It seems that the army account is more likely to be correct on details, though that too may be questionable because of its natural bias toward the whites.

Good Will Toward Men

The Battle of Cibecue Creek was chaotic, with Apaches fortified on the low hill on the west side of the creek shooting at the army encampment on the east side. In the first few minutes of the fight, the handcuffed Nockaydelklinne fell to the ground and while attempting to crawl away from battle, a sergeant shot him in the legs before a trumpeter named William O. Benites fired a round through the medicine man’s neck with his revolver.

When the medicine man’s son saw this, he rushed in on a horse but was killed. Nockaydelklinne’s wife then grabbed a revolver and tried to exact revenge on her husband’s murderers. She was also quickly slain.

As the fight wore down that afternoon, a sergeant named John A. Smith saw that Nockaydelklinne was still alive. According to Apache accounts, he hewed the medicine man’s head off with a hatchet.

Smith then examined a medal that belonged to the medicine man. It was from President Grant. On one side it read “Let us have peace.” On the other it read, “On earth peace, good will toward men.”

Fighting stopped in the evening and the army buried its dead.

In the end, six privates and Captain Hentig were killed, as were 18 Apaches. Around midnight, Carr withdrew the army to Fort Apache, where they arrived on August 31.

Aftermath of the Battle of Cibecue Creek

In the aftermath of the battle, fighting continued.

On September 1, Apaches attacked Fort Apache with scattered gunfire, and nine soldiers were killed along Turkey Creek. Meanwhile, Apache families fled the area, sensing that violence was going to escalate.

Other Apache warriors and families who had been loyal to the army abandoned the fort and fled. It would be months before the Apache refugees would return to the reservation.

As for the Apache scouts who turned on the army at Cibecue Creek, five were arrested and brought before a military tribunal. Two were sentenced to Alcatraz but were paroled in 1884.

It was thought that many of the Apache scouts had just been swept up in the mutiny. The other three, which included Dead Shot, were executed by hanging on March 3, 1882. Before their deaths, all three proclaimed innocence and Dead Shot tried to escape.

Cibecue Creek is remarkable in being the worst military loss of the U.S. Army in Arizona’s history. It is also the only time that Apache scouts mutinied in their service to the army. The fight marks an escalation in the Apache Wars which led to a lingering insurgency that didn’t end until the capture of Geronimo in 1886.

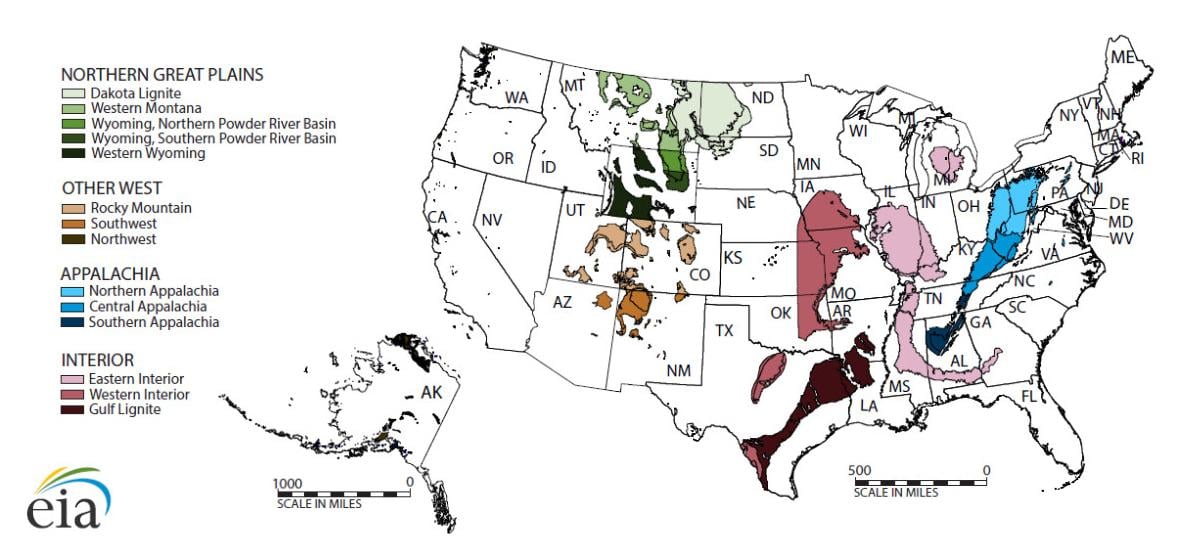

And we now turn to what has reared its ugly political and economic justice head to worry the ACME executive council and President Grover Cleveland.

And we now turn to what has reared its ugly political and economic justice head to worry the ACME executive council and President Grover Cleveland.