Post by miletus12 on Apr 8, 2023 0:45:07 GMT

Apr 7, 2023 20:44:36 GMT 575 said:

I had this hunch of where is Tesla in all of this - so there he is. Did look him up and alternate current though didn't read it all. Found something about an Austrian Company making lamps on AC and thought then thats it - but when then all the jazz about Tesla.

I also wondered about the cutting down of long work hours in your country as well as in mine. It even lingered on during my first years in school - as my folks went to work saturday so did I go to school.

It is emancipation of the peoples not just women but thats half of it. Well the Socialdemocratic Party herearounds fought industry for decades to change that - and did in Scandinavia and other parts of Europe - not all though. As I wrote in the 1914 ISOT during 1911 that struggle made for 600,000 lost work days in Denmark.

There's a reason to why we cherished this situation - seems a lot of peoples have forgotten this today.

Second, if you look at rotating magnetic fields after Gramme and Pacinotti and I do not know, maybe Siemans and a dozen other European inventors, you still find in front of them, that Croatian patriot, Tesla, who understood the three phases of the rotating magnetic fields that are at the heart of many electric motors, either AC or DC, and who worked the mechanics out of those three, six, nine, multiples of three, etc., pole electric motors and who designed commutators and coil wraps for the stators and rotors that still befuddle electrical engineers today. We use his now standard designs for everything from small micro-motors to huge final drives. It was a set of Tesla modelled motors that were the final drives on the largest fastest turbo-electric ships ever built; the French liner SS Normandie and the American navy's Lexington class aircraft carriers.

Those (DC) motors and electric generators, turned by diesel engines, form the heart of the current American locomotive fleet.

Third, cutting long work hours is a function of access to "automation". Let me give you an example:

or

or

That was state of the American art, six years before this story begins. Both models featured a manually operated paddle board inside the "barrel" that you had to fill with a bucket of presumably hot water, you boiled in a large pot on your coal fired stove or in your wood burning fireplace. These machines were "small" by capacity allowing no more than 4-5 kgs of clothes to be washed at a time. The time to prepare the machine, that is load the barrel, mix the detergent and inssert the clothes took at least an hour. Then after cranking on the thing for a half hour, the operator, could remove the "washed clothes" and run them through the ringer (dismountable so you could load the barrel) before putting them on a clothes line to dry. After the clothes dried (takes 2 to 3 hours) then the operator took one of these things off the fire,

and using a dip and press technique, "ironed" the clothes. This was actually labor saving in the 1870 context, because it sure beat the heck out beating clothes by a river bank for a couple of days, waiting for the Native Americans to chase you away from their watering hole that you had just polluted with poisonous lye, and it sure gave much cleaner clothes at less cost in time and money. Washing clothes could become a weekly day long chore instead of a once a month two or three day labor marathon.

We, Americans, stank because most of us could not afford the time to wash clothes as often as we do now. We found other regrettable ways to handle that laundry problem.

Yick Wo: How A Racist Laundry Law In Early San Francisco Helped Civil Rights

By Diana Fan - Published on August 23, 2015.

The next time you pass the parking lot on Third Street between St. Francis Place and Harrison Street, imagine a laundry named Yick Wo housed there.

It was the scene of one of the earliest legal victories for civil rights in the modern era.

Lee Yick, a Chinese laundry store owner, took the city all the way to the Supreme Court over discriminatory enforcement of a fire-safety ordinance—and won—in 1886.

The Yick Wo case, as it came to be known, was the first time the 14th Amendment's Equal Protection Clause was used strike down a law that is seemingly written to apply to everyone, but ends up being unequally enforced. It would become part of the foundation for dozens of other civil rights rulings in later decades.

Here's a closer look at the historical context of the case through legal journal articles and the book, In Search of Equality: The Chinese Struggle Against Discrimination in Nineteenth Century America by UC Berkeley professor Charles McClain, and how the decision introduced new legal ideas that would become the basis for other important civil rights cases.

Gold Rush Tensions

The call of the Gold Rush of 1849 was heard not only by North Americans who come out west to seek their fortune, but was it also the impetus for the first large scale migration of Chinese Americans to the United States. The men who came to California to mine for gold ended up with a lot of dirty clothes that they weren’t willing to clean themselves because laundry was considered women’s work. And since most of the incoming migration west consisted of men, there was a shortage of women to do this laundry. The local Spanish and Native American women charged such high prices for laundry service that many men found it cheaper to ship their laundry to Hong Kong and wait months for the return of their clothes. Eventually, Chinese men came to fill this demand since Chinese miners were facing a discriminatory Foreign Miners Tax and providing laundry services gave the Chinese men another way to establish a financial foothold in the US.

With the end of the Gold Rush came a growing number of unemployed men who feared that immigrants were stealing away jobs and a growing fear that the Chinese immigrants were willing to work for long hours in terrible conditions, which would decrease pay and work availability for all. Added to this was the completion of the Transcontinental Railroad in 1869, which meant more Chinese looking for work and willing to work in low-paying jobs. From 1877 to 1887, there were protests and riots, sometimes violent and murderous. In 1878, the political party Workingmen’s Party of California was established with an anti-Chinese immigrant agenda. They successfully campaigned to add a provision to the California constitution that prohibited companies from employing Chinese and denied Chinese residents property protections. In 1882, Congress passed the Chinese Exclusion Act which holds the dubious honor of being the first law to prevent a specific ethnic group from immigrating.

Anti-Laundry Legislation

The San Francisco Supervisors responded to this anti-immigration and anti-Chinese environment by passing more than a dozen ordinances against laundries from 1873 to 1883. The ordinances targeted the laundries in various ways, such as by imposing a maximum hour rule so that different laundry owners could not share one laundry space, zoning rules to push laundries from white neighborhoods to the outskirts of town or to toxic industrial areas, taxes on laundries with horse-drawn vehicles, prohibiting drying racks on roofs, and banning the use of a mouth tube to squirt starch on clothes, which was a common practice by Chinese laundries.

On February 5, 1880, a fire broke out in a Chinese operated laundry that killed 11 of the 13 residents according to the Chronicle. The fire was started when one of the workers arose and was careless with a candle that set the clothes drying on lines on fire. At the first Supervisors meeting after the fire, a supervisor named Charles Taylor proposed an ordinance that would regulate all buildings used by the Chinese as laundries as requiring Board approval. At this meeting, the Supervisors also asked the city attorney to determine the legality of an ordinance that would “restrict and confine the keeping and carrying on of laundries by the Chinese to a certain designated portion of this city and county” which provides a bit of insight into the Supervisors’ intentions at the meeting. When the Supervisors passed the finalized version of Order No. 1569, which stated that it would be illegal for any person to operate a laundry in a wood building in the city and county of San Francisco without permission from the Supervisors, the provisions regarding Chinese owned laundries was removed because of concern that it would be unconstitutional. Violation of Order No. 1569 would be a misdemeanor and a fine of $1000, imprisonment for a maximum of six months, or both.

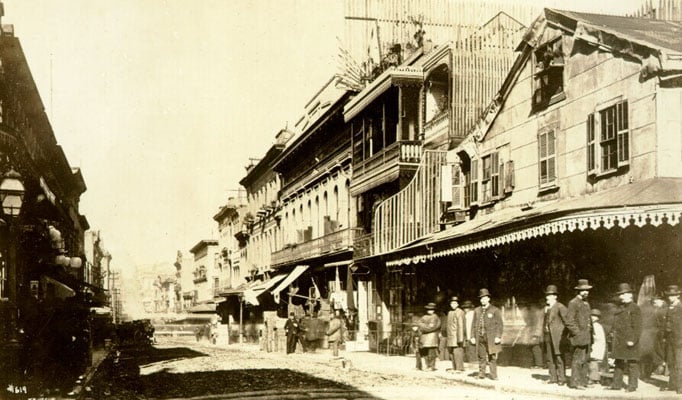

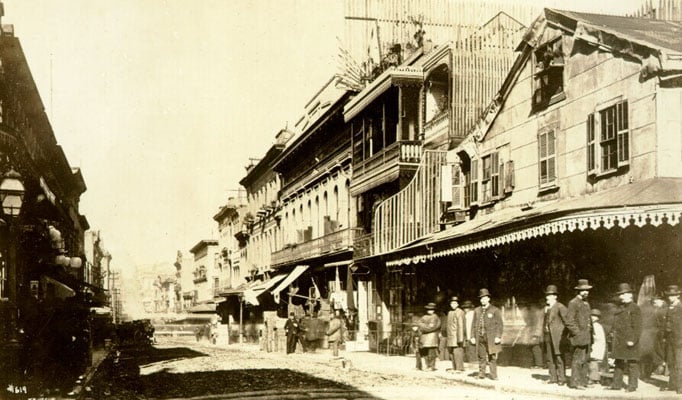

Chinatown in 1880 at Grant and Clay. Photo by T.E. Hecht via the San Francisco Public Library.

From 1880 to 1885, lower level police courts did find Order No. 1569 unconstitutional because it gave too much power to the Board of Supervisors to deprive people of their property. The police, who continued to enforce the ordinance, basically ignored these lower level court decisions.

On June 10, 1882, a San Francisco Supervisor approved ordinance that prohibited laundries from operating without permission from 12 neighbors went into effect because some people had been complaining that the presence of Chinese laundries were depreciating their home values.

Quong Woo had been operating a laundry for eight years in his neighborhood with proper permitting, but was found in violation of this law. He applied to the federal court stating:

In August of that year, the federal courts invalidated the ordinance as unconstitutional, noting that the Supervisors could not delegate their authority to regulate trades and professions to other people, but again the decision was not based on the idea of the constitutional protection of the 14th Amendment.

Lee Yick, Not Yick Wo

The right facts to test the legality of Order No. 1569 came with Lee Yick, a man who had been running his laundry at the same location for 22 years after arriving in the US in 1861. Both the Board of Fire Wardens and health department had inspected and certified laundry to be safe and satisfactory in 1884 before he applied for a renewal of his business license on June 1, 1885.

He was denied a month later, when the new law went into effect, and was arrested on August 22, 1885 and jailed for refusing to pay the $10 fine. The sheriff of San Francisco at the time, Peter Hopkins, booked him as Yick Wo, assuming that was his name because that was the name of the laundry, which was a common name for a laundry at the time and meant to signify harmony and tranquility.

Two days later on August 24, 1885, his lawyers filed a habeas corpus petition to California Supreme Court. (Habeas corpus means "bring the body" forward in Latin, and in US law such petitions provide detained persons a way to seek relief from imprisonment.)

An anti-racist cartoon by Thomas Nast in Harper's Weekly, April 1, 1882. "E-Pluribus Unum (except the Chinese)." Via the Thomas Nast Cartoon site – which has a great many more contemporary cartoons on the issue.

On December 29, 1885 the California Supreme Court upheld the ordinance finding that fire prevention is a legitimate reason for a law and that everyone must suffer for the benefit of the general good.

Yick’s lawyers attempted to file in the Federal Circuit Court but were denied for procedural reasons. On January 29, 1886, his lawyers filed with the Supreme Court and a decision was made on May 10, 1886. The case was filed and combined with another Chinese laundry owner, Wo Lee, who had also passed inspection by the fire warden of his laundry that had been operating for 25 years and also refused to pay the $10 fine.

Supreme Court and Historical Relevance

The Supreme Court case starts out by describing the laundry statistics in city in 1880. At that time, there were 320 laundries in the city and county of San Francisco and 310 of them were made of wood. 240 of the 310 laundries were owned by Chinese. At this time, 9 out of 10 buildings in San Francisco were made of wood, but there were no ordinances regulating other industries. The Justices find that 150 Chinese laundry owners had been arrested for not having received permission to operate from the Supervisors. However, 80-some white-owned laundries continued to operate without the Sheriff requiring proof of Supervisor approval and the Supervisors granted all but one of the white-owned laundry applicants. The Supreme Court said that with such stark numbers between the races and no other reasonable explanation of the differences between white and Chinese owned laundries, the only explanation could be “hostility to the race and nationality to which the petitioners belong.”

The Supreme Court ruled on May 10, 1886 that an unequal application of a facially neutral law was a violation of the Equal Protection Clause of the 14th Amendment, which guarantees equal application of the laws. While the ordinance didn’t mention Chinese laundrymen as the target, the statistics of how it was enforced shows that it ended up being a racially discriminatory law and thus unconstitutional, violating this part of the 14th Amendment:

No State shall make or enforce any law which shall abridge the privileges or immunities of citizens of the United States; nor shall any State deprive any person of life, liberty, or property, without due process of law; nor deny to any person within its jurisdiction the equal protection of the laws.

This ruling made Yick Wo the first case to use the Equal Protection Clause to strike down a law that may be written to apply to everyone, but is enforced in unequal ways.

The sentence in the 14th Amendment would go on to become the Supreme Court’s basis for declaring other state laws regarding interracial marriage, segregated schools, segregation in housing, voting rights, disability rights, gender discrimination, and most recently in recognizing gay marriage.

The Yick Wo case has been cited by the Supreme Court over 150 times, including in Hirabayashi v. United States, the case contesting the curfews placed on Japanese Americans in World War II, which recognized that regulations based on nationality must satisfy a higher level of scrutiny when applying the Equal Protection Clause.

But at the time, the local reaction to the Yick Wo decision was negative. An editorial in the San Francisco Evening Bulletin claimed that the Supreme Court was overstepping its bounds by not recognizing the inherent differences between the way white and Chinese laundries operate. The editorial claimed that the Supreme Court decision limited the ways left to “elevate or reform them” because it would be considered discriminatory and the only option left was total exclusion. On the other hand, Chinatown celebrated the decision with fireworks.

The case is also notable because Yick was not a citizen of the United States at the time. The Supreme Court ruled that the 14th Amendment still applied to a non-citizen because the 14th Amendment applies to any person and is not limited to citizens.

While the the Yick Wo decision may not be as well-known today as other Supreme Court rulings, it is still a piece of San Francisco’s contribution to the civil rights movement.

And the city, in later years, did figure out a way to acknowledge Yick and his case – an elementary school in Russian Hill now bears the name.

San FranciscoSoMa

By Diana Fan - Published on August 23, 2015.

The next time you pass the parking lot on Third Street between St. Francis Place and Harrison Street, imagine a laundry named Yick Wo housed there.

It was the scene of one of the earliest legal victories for civil rights in the modern era.

Lee Yick, a Chinese laundry store owner, took the city all the way to the Supreme Court over discriminatory enforcement of a fire-safety ordinance—and won—in 1886.

The Yick Wo case, as it came to be known, was the first time the 14th Amendment's Equal Protection Clause was used strike down a law that is seemingly written to apply to everyone, but ends up being unequally enforced. It would become part of the foundation for dozens of other civil rights rulings in later decades.

Here's a closer look at the historical context of the case through legal journal articles and the book, In Search of Equality: The Chinese Struggle Against Discrimination in Nineteenth Century America by UC Berkeley professor Charles McClain, and how the decision introduced new legal ideas that would become the basis for other important civil rights cases.

Gold Rush Tensions

The call of the Gold Rush of 1849 was heard not only by North Americans who come out west to seek their fortune, but was it also the impetus for the first large scale migration of Chinese Americans to the United States. The men who came to California to mine for gold ended up with a lot of dirty clothes that they weren’t willing to clean themselves because laundry was considered women’s work. And since most of the incoming migration west consisted of men, there was a shortage of women to do this laundry. The local Spanish and Native American women charged such high prices for laundry service that many men found it cheaper to ship their laundry to Hong Kong and wait months for the return of their clothes. Eventually, Chinese men came to fill this demand since Chinese miners were facing a discriminatory Foreign Miners Tax and providing laundry services gave the Chinese men another way to establish a financial foothold in the US.

With the end of the Gold Rush came a growing number of unemployed men who feared that immigrants were stealing away jobs and a growing fear that the Chinese immigrants were willing to work for long hours in terrible conditions, which would decrease pay and work availability for all. Added to this was the completion of the Transcontinental Railroad in 1869, which meant more Chinese looking for work and willing to work in low-paying jobs. From 1877 to 1887, there were protests and riots, sometimes violent and murderous. In 1878, the political party Workingmen’s Party of California was established with an anti-Chinese immigrant agenda. They successfully campaigned to add a provision to the California constitution that prohibited companies from employing Chinese and denied Chinese residents property protections. In 1882, Congress passed the Chinese Exclusion Act which holds the dubious honor of being the first law to prevent a specific ethnic group from immigrating.

Anti-Laundry Legislation

The San Francisco Supervisors responded to this anti-immigration and anti-Chinese environment by passing more than a dozen ordinances against laundries from 1873 to 1883. The ordinances targeted the laundries in various ways, such as by imposing a maximum hour rule so that different laundry owners could not share one laundry space, zoning rules to push laundries from white neighborhoods to the outskirts of town or to toxic industrial areas, taxes on laundries with horse-drawn vehicles, prohibiting drying racks on roofs, and banning the use of a mouth tube to squirt starch on clothes, which was a common practice by Chinese laundries.

On February 5, 1880, a fire broke out in a Chinese operated laundry that killed 11 of the 13 residents according to the Chronicle. The fire was started when one of the workers arose and was careless with a candle that set the clothes drying on lines on fire. At the first Supervisors meeting after the fire, a supervisor named Charles Taylor proposed an ordinance that would regulate all buildings used by the Chinese as laundries as requiring Board approval. At this meeting, the Supervisors also asked the city attorney to determine the legality of an ordinance that would “restrict and confine the keeping and carrying on of laundries by the Chinese to a certain designated portion of this city and county” which provides a bit of insight into the Supervisors’ intentions at the meeting. When the Supervisors passed the finalized version of Order No. 1569, which stated that it would be illegal for any person to operate a laundry in a wood building in the city and county of San Francisco without permission from the Supervisors, the provisions regarding Chinese owned laundries was removed because of concern that it would be unconstitutional. Violation of Order No. 1569 would be a misdemeanor and a fine of $1000, imprisonment for a maximum of six months, or both.

Chinatown in 1880 at Grant and Clay. Photo by T.E. Hecht via the San Francisco Public Library.

From 1880 to 1885, lower level police courts did find Order No. 1569 unconstitutional because it gave too much power to the Board of Supervisors to deprive people of their property. The police, who continued to enforce the ordinance, basically ignored these lower level court decisions.

On June 10, 1882, a San Francisco Supervisor approved ordinance that prohibited laundries from operating without permission from 12 neighbors went into effect because some people had been complaining that the presence of Chinese laundries were depreciating their home values.

Quong Woo had been operating a laundry for eight years in his neighborhood with proper permitting, but was found in violation of this law. He applied to the federal court stating:

That there now exist, and have existed for years, with the residents of the city and county of San Francisco, and its citizens and tax-payers, great antipathy and hatred toward the people of his race; that combinations among such residents have been formed to drive them from the country; that in consequence of this feeling it has been impossible for him to obtain the recommendation of 12 citizens and tax-payers to carry on his business in the block.

Lee Yick, Not Yick Wo

The right facts to test the legality of Order No. 1569 came with Lee Yick, a man who had been running his laundry at the same location for 22 years after arriving in the US in 1861. Both the Board of Fire Wardens and health department had inspected and certified laundry to be safe and satisfactory in 1884 before he applied for a renewal of his business license on June 1, 1885.

He was denied a month later, when the new law went into effect, and was arrested on August 22, 1885 and jailed for refusing to pay the $10 fine. The sheriff of San Francisco at the time, Peter Hopkins, booked him as Yick Wo, assuming that was his name because that was the name of the laundry, which was a common name for a laundry at the time and meant to signify harmony and tranquility.

Two days later on August 24, 1885, his lawyers filed a habeas corpus petition to California Supreme Court. (Habeas corpus means "bring the body" forward in Latin, and in US law such petitions provide detained persons a way to seek relief from imprisonment.)

An anti-racist cartoon by Thomas Nast in Harper's Weekly, April 1, 1882. "E-Pluribus Unum (except the Chinese)." Via the Thomas Nast Cartoon site – which has a great many more contemporary cartoons on the issue.

On December 29, 1885 the California Supreme Court upheld the ordinance finding that fire prevention is a legitimate reason for a law and that everyone must suffer for the benefit of the general good.

Yick’s lawyers attempted to file in the Federal Circuit Court but were denied for procedural reasons. On January 29, 1886, his lawyers filed with the Supreme Court and a decision was made on May 10, 1886. The case was filed and combined with another Chinese laundry owner, Wo Lee, who had also passed inspection by the fire warden of his laundry that had been operating for 25 years and also refused to pay the $10 fine.

Supreme Court and Historical Relevance

The Supreme Court case starts out by describing the laundry statistics in city in 1880. At that time, there were 320 laundries in the city and county of San Francisco and 310 of them were made of wood. 240 of the 310 laundries were owned by Chinese. At this time, 9 out of 10 buildings in San Francisco were made of wood, but there were no ordinances regulating other industries. The Justices find that 150 Chinese laundry owners had been arrested for not having received permission to operate from the Supervisors. However, 80-some white-owned laundries continued to operate without the Sheriff requiring proof of Supervisor approval and the Supervisors granted all but one of the white-owned laundry applicants. The Supreme Court said that with such stark numbers between the races and no other reasonable explanation of the differences between white and Chinese owned laundries, the only explanation could be “hostility to the race and nationality to which the petitioners belong.”

The Supreme Court ruled on May 10, 1886 that an unequal application of a facially neutral law was a violation of the Equal Protection Clause of the 14th Amendment, which guarantees equal application of the laws. While the ordinance didn’t mention Chinese laundrymen as the target, the statistics of how it was enforced shows that it ended up being a racially discriminatory law and thus unconstitutional, violating this part of the 14th Amendment:

No State shall make or enforce any law which shall abridge the privileges or immunities of citizens of the United States; nor shall any State deprive any person of life, liberty, or property, without due process of law; nor deny to any person within its jurisdiction the equal protection of the laws.

This ruling made Yick Wo the first case to use the Equal Protection Clause to strike down a law that may be written to apply to everyone, but is enforced in unequal ways.

The sentence in the 14th Amendment would go on to become the Supreme Court’s basis for declaring other state laws regarding interracial marriage, segregated schools, segregation in housing, voting rights, disability rights, gender discrimination, and most recently in recognizing gay marriage.

The Yick Wo case has been cited by the Supreme Court over 150 times, including in Hirabayashi v. United States, the case contesting the curfews placed on Japanese Americans in World War II, which recognized that regulations based on nationality must satisfy a higher level of scrutiny when applying the Equal Protection Clause.

But at the time, the local reaction to the Yick Wo decision was negative. An editorial in the San Francisco Evening Bulletin claimed that the Supreme Court was overstepping its bounds by not recognizing the inherent differences between the way white and Chinese laundries operate. The editorial claimed that the Supreme Court decision limited the ways left to “elevate or reform them” because it would be considered discriminatory and the only option left was total exclusion. On the other hand, Chinatown celebrated the decision with fireworks.

The case is also notable because Yick was not a citizen of the United States at the time. The Supreme Court ruled that the 14th Amendment still applied to a non-citizen because the 14th Amendment applies to any person and is not limited to citizens.

While the the Yick Wo decision may not be as well-known today as other Supreme Court rulings, it is still a piece of San Francisco’s contribution to the civil rights movement.

And the city, in later years, did figure out a way to acknowledge Yick and his case – an elementary school in Russian Hill now bears the name.

San FranciscoSoMa

While the point of the racism is also part of this alternative history, I want you to understand "why" there were so many Chinese laundries. The "whites" of the era, who were middle class in our cities, but who could not afford household servants, or who did not have access to a river and women who could spend two days a month beating the lice out of the clothes and letting nature's river currents wash and rinse the stinky things, would take their laundry once a week to such a Chinese or "other" laundry, to have the hard-working yet despised people who worked in that laundry render their clothes fit for wear. It took a dozen or more people to wash those clothes in the "next day ready service" that such establishments guaranteed. Sixteen hour days washing other people's clothes, was many a Chinese-American's start of life here.

Think of how electric powered washing machines would have helped tham?

:format(webp):no_upscale()/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/7317511/1889view.jpg)