The Filipino American War as seen by diarists in real time with some additional commentary and sourc

Jul 10, 2023 0:36:41 GMT

gillan1220 likes this

Post by miletus12 on Jul 10, 2023 0:36:41 GMT

Diary of James J. Loughrey July 9, 1899

1. The preliminary indications are that the 1st California Flour Mill Thieves were heading home.

We were relieved by the 6th US Infantry.

The Experiences of the

First California Volunteer Infantry

General:

The First California Regiment, under the command of Col. James S. Smith, served in the Philippines both during the Spanish American War, and during part of the Philippine-American War. The unit was mustered into service on May 7, 1898 at San Francisco California. At this time, the unit consisted of fifty-one officers and 986 enlisted men.

On May 25, the 1st California steamed for the Philippines, where it arrived on June 30. The unit took part in actions on July 31, 1898 (near Malate) and in the capture of Manila on August 13, 1898. In the former it lost one man killed, and ten wounded, and in the latter one man killed and two wounded. The Philippine-American War began on February 4, 1899. On July 26, 1899, the First California Volunteer Infantry left the Philippines for the United States, arriving in the U.S. on August 24, 1899. The unit was mustered out of service on September 21, 1899. At the time of muster out, the unit consisted of fifty officers and 999 enlisted men.

During its term of service, the unit had one officer who died of wounds received in battle. In addition, eight enlisted men were killed in action, one man died from wounds received in battle. twenty-four died from disease, two died as the result of accidents and one man drown. Also forty-three men were discharged on disability and seven men deserted.

The experiences:

It will be remembered by many of us, that California mustered two of its State Militia regiments for Philippine service. One was the First, and the other was the Seventh. The First California took its rush training, was mustered into the U. S. forces, and left San Francisco May 26, 1898, with the rest of the expedition, on the transportsCity of Pekin, Australia, and City of Sydney, 115 officers and 2386 enlisted men.

The transports of the First Expedition were joined at Honolulu by the U. S. Cruiser Charleston which had waited for them. The Captain of the Charleston had sealed orders to be opened after leaving Honolulu, which orders when read in due time, directed him to stop enroute and capture Guam Island.

On reaching Guam, the Charleston entered the narrow channel, steamed to a position in front of Fort Santa Cruz, and sent a dozen shots over it from three-pounders. Soon a boat came off with some Spanish officers who apologized for not returning the "salute", as they had no ammunition. They were astonished and chagrined to learn that it was not a salute, and that their immediate surrender was demanded. The two regiments, one Spanish and one native, were disarmed, the. former taken on board the transports as prisoners, the latter disbanded, much to their delight. The Stars and Stripes were raised over the fort, and the national salute fired from the guns of the cruiser. More like a drama than real war, this incident gave to the United States an island that has not only been extremely useful as a station for naval and airplane use, but when it was proposed in 1939 to fortify it and construct a real naval base, became suddenly a very contentious subject, both in and out of Congress, and with another interested nation some 1500 miles to the north.

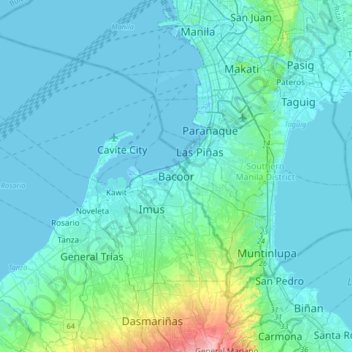

The troops of the First Expedition were, on arrival in Manila Bay, at first taken to Cavite, but later moved to Camp Dewey, by the Bay, south of Manila. Joined later by the Second and Third Expeditions this comprised the American forces with which the capture of Manila was effected.

Here we may take an aside. The accounts we referred to above also contain an interesting account by a war correspondent, O. K. Davis, who obtained passes from General Aguinaldo to visit the Filipino trenches at Paranaque, some miles south of Manila, which faced those of the Spaniards who defended Manila, and before any American troops had been landed or any place in the line taken by them. The Filipino position was commanded by General Mariano Noriel. Davis, on this tour of inspection, noted the shooting of the Spanish troops, which he states was always very high, and saw no evidences of bullets low enough to endanger the Filipinos, even had they not been behind earthworks. He met a Spanish deserter who told him that the Spanish defenders of Manila were in desperate straits, and that the Germans, through the German Admiral Von Diederichs were helping the Spaniards of the city in many ways, al of which was well known to Dewey. A few days later he made another trip, seeing the smooth-bore guns of the Filipinos go into action, against these Spanish works, which 'resulted in a retreat of the Spanish forces to Malate.

Later the American troops had landed and camped at a place called Camp Dewey, another correspondent, F. D. Millet, with General Greene's command, observed that the Americans had intrenched from the sea-shore eastward, a distance of nearly a mile, to a point beyond the Pasay road. The American trenches were only about 250 yards from Blockhouse No 14….and in direct contact with an-extensive system of Spanish trenches and rifle-pits. This position was taken by the American somewhat in advance of the Filipino line, which was still occupying the position in rear of the American advance line, but in front, of the American reserve. This gave rise to trouble, as the Filipinos fired wildly from behind the American line, using cannon (bearing dates 1803 and 1874), and thereby drawing a return fire from the Spanish trenches that killed 3 and wounded 7 of the 23rd Regulars.

Between the American front line and Malate and Singalong were impassable swamps, crossed only by the Pasay Road and Calle Real, both of these roads so deep in mud that only native carabaos could travel them. A south-western monsoon made the bay very rough, and the landing of the California Volunteers, the 14th and 23rd Regulars from cascos on the beach was carried out with very great difficulties.

It was in this position, taken to keep ahead of the troops of General Noriel in the advance on Manila - a necessity plainly seen - that the American troops held on, waiting for the cooperation of the Navy for the forward movement. Correspondent Millet wrote that the Third Expedition forces had just arrived at Camp Dewey, and that a tropical downpour of rain had lasted for a week, every soldier soaked to the skin, most of the men in only half uniform or in under-clothes, but no illness, no damped spirits, eager loyalty to General Greene, whose fine example had won the unbounded confidence of his men.

Correspondent Bass writes how Dewey waited the arrival the monitors Monterey and Monadnock, with their heavy guns to match the Spanish 10-inch guns in Manila, as his cruisers had nothing adequate for such an encounter. It was reported that the German Admiral Von Diederich would not allow Dewey to bombard Manila. That matter however was settled by the firmness of the Commodore, who soon put the German into his proper place. Bass says the field artillery firing of the Spanish was very accurate and effective. The Spanish infantry made a spirited night attack on the American position, but were driven back. He adds that the lst California volunteers are rapidly developing into seasoned troops, cool as old veterans. He also notes growing strain in the relations of the Americans with the forces of the insurgents under General Aguinaldo.

From August 2 to 13, the Americans were ready to advance, but were waiting, they knew not why. But "the day" 'did come, and orders were given. First Brigade under Gen. MacArthur on the right, Second Brigade under Gen. Greene on the left (beach) combined attack by sea and land at 10 o'clock, morning of August 13, a Saturday….The California Volunteers did their part well.

After the capture of Manila, and the receipt of the news of the peace with Spain, General Merritt left for Paris and General Greene for Washington, while General Anderson took command in Manila.

General AndersonGeneral Anderson explains that the origin of the controversies and conflicts with the Insurgents was due to the refusal of the Americans to recognize the political authority of General Aguinaldo, he having received orders from General Merritt to forbid the insurgents from entering Manila. He therefore sent a battalion of the North Dakotas to hold a bridge the Filipino forces would have to cross if they attempted to follow the American forces into Manila. The latter however, found a way in through Santa Ana, about 4000 of them taking possession of Paco and part of Malate. To hold them in these positions, a cordon of American troops was thrown around them. General Anderson 'requested General Aguinaldo to withdraw these troops, the situation having become dangerous. After some parley and protest, the Filipino troops were somewhat retired, but the danger not entirely averted. Later, by repeated demands, all insurgents were removed from Manila, creating a state of bad feeling between the Americans and the Filipinos, which was later to develop into open hostilities.

It will be necessary for us to consider this state of affairs between the American and Insurgent forces with understanding and fairness. Most of the men involved in the fighting that broke out February 4, 1899, and developed into a hard campaign for the Americans, especially those who returned to the homeland in 1899, while hostilities were still severe, have unfortunately carried - and continue to hold - an unfair view of the motives behind the actions of the insurgents. The several war correspondents with our troops observed at first hand, as did most of the officers, that the Filipinos really had, from their own point of view, considerable right for protest and deep chagrin at the way they were denied participation in the capture and occupation of Manila. They had fought the Spaniards for several years before the arrival of the Americans, and had driven them back into Manila, holding them there with a complete ring of their forces on the land side. And they had understood that the Americans had taken them as allies. When not permitted to enter Manila as troops of occupation, they thought themselves deprived of their just rights. This was admitted in substance by General Otis, and he carefully explained his position again and again, telling them that such were his orders from Washington, and asking Aguinaldo's men to be patient and wait the action of Congress in the matter of their recognition.

In fairness, on the other side of the question, we must not forget that there was much misleading propaganda among the Filipinos by their radical leaders, especially after the more conservative Filipinos with General Aguinaldo had resigned and were replaced by others, some of whom seemed to be advancing their own interests more than the good of their country. General Aguinaldo was inclined to co-operate with the American Military Governor, but he had good reason to fear treachery among the officers who surrounded him, for on several occasions they plotted against him, and once he had, with loyal troops, to put down revolt behind his own lines. Many of his generals were very unwilling to obey his orders, one case being that of a Filipino general who was abusing his authority, and whom General Aguinaldo ordered to transfer to another province. This general replied to his chief that he would remain where he was, and if General Aguinaldo wanted to move him, he could come and try it. And he stayed just where he was until, two years later, driven with a much reduced force into the mountains, he was forced to surrender. It was the manner of fighting practiced by some of these insubordinate generals, contrary to the rules of civilized warfare, that so inflamed the American troops, who hated treachery above all things. And it was the abuses by these same Filipino leaders, and encouraged among their forces, on their own people, non-combatants entitled to their protection, that steadily alienated the support of the population from the Insurgent cause, and an important factor in the failure of the campaigns attempted by General Aguinaldo.

Some time after the capture of Manila, Colonel Smith was detached from his regiment and sent to Negros. In a short time he found conditions there more serious than he expected, and asked for his own regiment, the First California, to be sent to him.

The 3rd battalion was sent to Bacolod, Negros, on March 4, 1899, followed by the next battalion on March 22, and the remaining one on May 21.

View of the First California Volunteer Infantry

A view of part of the 1st California Volunteer Infantry

BIBLIOGRAPHY:

Clerk of Joint Committee on Printing, The Abridgement of Message from the President of the United States to the Two Houses of Congress. (Washington: Government Printing Office, 1899.) Vol 3, 95, 96, 493. (General info., above)

Harper's Weekly (New York: June 11,1898), 580 (image of troops on City of Peking).

Statistical Exhibit of Strength of Volunteer Forces Called into Service During the War with Spain; with Losses from All Causes. (Washington: Government Printing Office, 1899).

Stickney, Joseph L., Admiral Dewey at Manila. (Chicago: Imperial Publishing Co., 1899). (image of Anderson).

"The First California Volunteer Regiment," The American Oldtimer. Vol. VII, No. 6 Manila, Philippines, April 1940, 5-10. (the main account, above).

Watson, Mark Alan (donated group photo, above through the courtesy of Deborah L. Richardson).

First California Volunteer Infantry

General:

The First California Regiment, under the command of Col. James S. Smith, served in the Philippines both during the Spanish American War, and during part of the Philippine-American War. The unit was mustered into service on May 7, 1898 at San Francisco California. At this time, the unit consisted of fifty-one officers and 986 enlisted men.

On May 25, the 1st California steamed for the Philippines, where it arrived on June 30. The unit took part in actions on July 31, 1898 (near Malate) and in the capture of Manila on August 13, 1898. In the former it lost one man killed, and ten wounded, and in the latter one man killed and two wounded. The Philippine-American War began on February 4, 1899. On July 26, 1899, the First California Volunteer Infantry left the Philippines for the United States, arriving in the U.S. on August 24, 1899. The unit was mustered out of service on September 21, 1899. At the time of muster out, the unit consisted of fifty officers and 999 enlisted men.

During its term of service, the unit had one officer who died of wounds received in battle. In addition, eight enlisted men were killed in action, one man died from wounds received in battle. twenty-four died from disease, two died as the result of accidents and one man drown. Also forty-three men were discharged on disability and seven men deserted.

The experiences:

It will be remembered by many of us, that California mustered two of its State Militia regiments for Philippine service. One was the First, and the other was the Seventh. The First California took its rush training, was mustered into the U. S. forces, and left San Francisco May 26, 1898, with the rest of the expedition, on the transportsCity of Pekin, Australia, and City of Sydney, 115 officers and 2386 enlisted men.

The transports of the First Expedition were joined at Honolulu by the U. S. Cruiser Charleston which had waited for them. The Captain of the Charleston had sealed orders to be opened after leaving Honolulu, which orders when read in due time, directed him to stop enroute and capture Guam Island.

On reaching Guam, the Charleston entered the narrow channel, steamed to a position in front of Fort Santa Cruz, and sent a dozen shots over it from three-pounders. Soon a boat came off with some Spanish officers who apologized for not returning the "salute", as they had no ammunition. They were astonished and chagrined to learn that it was not a salute, and that their immediate surrender was demanded. The two regiments, one Spanish and one native, were disarmed, the. former taken on board the transports as prisoners, the latter disbanded, much to their delight. The Stars and Stripes were raised over the fort, and the national salute fired from the guns of the cruiser. More like a drama than real war, this incident gave to the United States an island that has not only been extremely useful as a station for naval and airplane use, but when it was proposed in 1939 to fortify it and construct a real naval base, became suddenly a very contentious subject, both in and out of Congress, and with another interested nation some 1500 miles to the north.

The troops of the First Expedition were, on arrival in Manila Bay, at first taken to Cavite, but later moved to Camp Dewey, by the Bay, south of Manila. Joined later by the Second and Third Expeditions this comprised the American forces with which the capture of Manila was effected.

Here we may take an aside. The accounts we referred to above also contain an interesting account by a war correspondent, O. K. Davis, who obtained passes from General Aguinaldo to visit the Filipino trenches at Paranaque, some miles south of Manila, which faced those of the Spaniards who defended Manila, and before any American troops had been landed or any place in the line taken by them. The Filipino position was commanded by General Mariano Noriel. Davis, on this tour of inspection, noted the shooting of the Spanish troops, which he states was always very high, and saw no evidences of bullets low enough to endanger the Filipinos, even had they not been behind earthworks. He met a Spanish deserter who told him that the Spanish defenders of Manila were in desperate straits, and that the Germans, through the German Admiral Von Diederichs were helping the Spaniards of the city in many ways, al of which was well known to Dewey. A few days later he made another trip, seeing the smooth-bore guns of the Filipinos go into action, against these Spanish works, which 'resulted in a retreat of the Spanish forces to Malate.

Later the American troops had landed and camped at a place called Camp Dewey, another correspondent, F. D. Millet, with General Greene's command, observed that the Americans had intrenched from the sea-shore eastward, a distance of nearly a mile, to a point beyond the Pasay road. The American trenches were only about 250 yards from Blockhouse No 14….and in direct contact with an-extensive system of Spanish trenches and rifle-pits. This position was taken by the American somewhat in advance of the Filipino line, which was still occupying the position in rear of the American advance line, but in front, of the American reserve. This gave rise to trouble, as the Filipinos fired wildly from behind the American line, using cannon (bearing dates 1803 and 1874), and thereby drawing a return fire from the Spanish trenches that killed 3 and wounded 7 of the 23rd Regulars.

Between the American front line and Malate and Singalong were impassable swamps, crossed only by the Pasay Road and Calle Real, both of these roads so deep in mud that only native carabaos could travel them. A south-western monsoon made the bay very rough, and the landing of the California Volunteers, the 14th and 23rd Regulars from cascos on the beach was carried out with very great difficulties.

It was in this position, taken to keep ahead of the troops of General Noriel in the advance on Manila - a necessity plainly seen - that the American troops held on, waiting for the cooperation of the Navy for the forward movement. Correspondent Millet wrote that the Third Expedition forces had just arrived at Camp Dewey, and that a tropical downpour of rain had lasted for a week, every soldier soaked to the skin, most of the men in only half uniform or in under-clothes, but no illness, no damped spirits, eager loyalty to General Greene, whose fine example had won the unbounded confidence of his men.

Correspondent Bass writes how Dewey waited the arrival the monitors Monterey and Monadnock, with their heavy guns to match the Spanish 10-inch guns in Manila, as his cruisers had nothing adequate for such an encounter. It was reported that the German Admiral Von Diederich would not allow Dewey to bombard Manila. That matter however was settled by the firmness of the Commodore, who soon put the German into his proper place. Bass says the field artillery firing of the Spanish was very accurate and effective. The Spanish infantry made a spirited night attack on the American position, but were driven back. He adds that the lst California volunteers are rapidly developing into seasoned troops, cool as old veterans. He also notes growing strain in the relations of the Americans with the forces of the insurgents under General Aguinaldo.

From August 2 to 13, the Americans were ready to advance, but were waiting, they knew not why. But "the day" 'did come, and orders were given. First Brigade under Gen. MacArthur on the right, Second Brigade under Gen. Greene on the left (beach) combined attack by sea and land at 10 o'clock, morning of August 13, a Saturday….The California Volunteers did their part well.

After the capture of Manila, and the receipt of the news of the peace with Spain, General Merritt left for Paris and General Greene for Washington, while General Anderson took command in Manila.

General AndersonGeneral Anderson explains that the origin of the controversies and conflicts with the Insurgents was due to the refusal of the Americans to recognize the political authority of General Aguinaldo, he having received orders from General Merritt to forbid the insurgents from entering Manila. He therefore sent a battalion of the North Dakotas to hold a bridge the Filipino forces would have to cross if they attempted to follow the American forces into Manila. The latter however, found a way in through Santa Ana, about 4000 of them taking possession of Paco and part of Malate. To hold them in these positions, a cordon of American troops was thrown around them. General Anderson 'requested General Aguinaldo to withdraw these troops, the situation having become dangerous. After some parley and protest, the Filipino troops were somewhat retired, but the danger not entirely averted. Later, by repeated demands, all insurgents were removed from Manila, creating a state of bad feeling between the Americans and the Filipinos, which was later to develop into open hostilities.

It will be necessary for us to consider this state of affairs between the American and Insurgent forces with understanding and fairness. Most of the men involved in the fighting that broke out February 4, 1899, and developed into a hard campaign for the Americans, especially those who returned to the homeland in 1899, while hostilities were still severe, have unfortunately carried - and continue to hold - an unfair view of the motives behind the actions of the insurgents. The several war correspondents with our troops observed at first hand, as did most of the officers, that the Filipinos really had, from their own point of view, considerable right for protest and deep chagrin at the way they were denied participation in the capture and occupation of Manila. They had fought the Spaniards for several years before the arrival of the Americans, and had driven them back into Manila, holding them there with a complete ring of their forces on the land side. And they had understood that the Americans had taken them as allies. When not permitted to enter Manila as troops of occupation, they thought themselves deprived of their just rights. This was admitted in substance by General Otis, and he carefully explained his position again and again, telling them that such were his orders from Washington, and asking Aguinaldo's men to be patient and wait the action of Congress in the matter of their recognition.

In fairness, on the other side of the question, we must not forget that there was much misleading propaganda among the Filipinos by their radical leaders, especially after the more conservative Filipinos with General Aguinaldo had resigned and were replaced by others, some of whom seemed to be advancing their own interests more than the good of their country. General Aguinaldo was inclined to co-operate with the American Military Governor, but he had good reason to fear treachery among the officers who surrounded him, for on several occasions they plotted against him, and once he had, with loyal troops, to put down revolt behind his own lines. Many of his generals were very unwilling to obey his orders, one case being that of a Filipino general who was abusing his authority, and whom General Aguinaldo ordered to transfer to another province. This general replied to his chief that he would remain where he was, and if General Aguinaldo wanted to move him, he could come and try it. And he stayed just where he was until, two years later, driven with a much reduced force into the mountains, he was forced to surrender. It was the manner of fighting practiced by some of these insubordinate generals, contrary to the rules of civilized warfare, that so inflamed the American troops, who hated treachery above all things. And it was the abuses by these same Filipino leaders, and encouraged among their forces, on their own people, non-combatants entitled to their protection, that steadily alienated the support of the population from the Insurgent cause, and an important factor in the failure of the campaigns attempted by General Aguinaldo.

Some time after the capture of Manila, Colonel Smith was detached from his regiment and sent to Negros. In a short time he found conditions there more serious than he expected, and asked for his own regiment, the First California, to be sent to him.

The 3rd battalion was sent to Bacolod, Negros, on March 4, 1899, followed by the next battalion on March 22, and the remaining one on May 21.

View of the First California Volunteer Infantry

A view of part of the 1st California Volunteer Infantry

BIBLIOGRAPHY:

Clerk of Joint Committee on Printing, The Abridgement of Message from the President of the United States to the Two Houses of Congress. (Washington: Government Printing Office, 1899.) Vol 3, 95, 96, 493. (General info., above)

Harper's Weekly (New York: June 11,1898), 580 (image of troops on City of Peking).

Statistical Exhibit of Strength of Volunteer Forces Called into Service During the War with Spain; with Losses from All Causes. (Washington: Government Printing Office, 1899).

Stickney, Joseph L., Admiral Dewey at Manila. (Chicago: Imperial Publishing Co., 1899). (image of Anderson).

"The First California Volunteer Regiment," The American Oldtimer. Vol. VII, No. 6 Manila, Philippines, April 1940, 5-10. (the main account, above).

Watson, Mark Alan (donated group photo, above through the courtesy of Deborah L. Richardson).