lordroel

Administrator

Posts: 67,964

Likes: 49,365

|

Post by lordroel on Jul 29, 2019 17:08:53 GMT

|

|

lordroel

Administrator

Posts: 67,964

Likes: 49,365

|

Post by lordroel on Jul 30, 2019 15:35:15 GMT

Day 1 of the Great War, July 28th 1914YouTube (The Outbreak of WWI - How Europe Spiraled Into the GREAT WAR)Newspapper: The Washington Times

1100: Austria-Hungary declares war on Serbia. 1500: Russian foreign minister Sazonov meets with the British ambassador to inform him that Russia will shortly mobilize against Austria and asks for British support of Russia and France. 1600: Sazonov meets with the French ambassador, who reiterates his country's commitment to Russia. 1700: The First Fleet is ordered to Scapa Flow. Other units of the Home Fleets are also ordered to their war stations. Throughout the day and evening, at the direction of Kaiser Wilhelm, Germany makes half-hearted, last-minute efforts to restrain Austria, suggesting that Austria only occupy Belgrade and then halt.

|

|

lordroel

Administrator

Posts: 67,964

Likes: 49,365

|

Post by lordroel on Jul 30, 2019 16:05:42 GMT

Day 2 of the Great War, July 29th 1914Austrian forces open the bombardment of Belgrade. Map: Brooklyn Daily Eagle

Kaiser Wilhelm and Tsar Nicholas begin exchanging a series of telegrams, trying to avert war between their countries. Russia orders partial mobilization, against Austria only.

|

|

lordroel

Administrator

Posts: 67,964

Likes: 49,365

|

Post by lordroel on Jul 30, 2019 16:07:58 GMT

Day 3 of the Great War, July 30th 1914

Russia: mobilization go up in cities across Russia

In Russia, the Tsar's decision of the previous evening to cancel general mobilization has appalled Foreign Minister Sazonov, War Minister General Vladimir Sukhomlinov, and Chief of Staff General Janushkevich, who all believe that any delay in mobilization threatens disaster on the battlefield. Tsar Nicholas II is at his summer residence in the Baltic, where Sazonov presses the case for general mobilization in the afternoon. The Tsar is nervous and irritable, caught between a hope that his cousin the Kaiser could be trusted in his stated desire for peace, and the arguments of his ministers. Finally, shortly after 4pm he submits to the arguments of Sazonov, and agrees once more to order general mobilization of the army. Sazonov telephones Janushkevich with the order, and concludes by saying 'Now you can smash your telephone' - Janushkevich had earlier declared that upon receiving such an order a second time, he would smash his telephone to prevent another change of heart by the Tsar from having any effect. The posters announcing mobilization go up in cities across Russia, with the first day of mobilization set for the 31st.

Germany: Chancellor Bethmann-Hollweg sends an urgent telegram to the German ambassador in Vienna

At 255am, Chancellor Bethmann-Hollweg sends an urgent telegram to the German ambassador in Vienna, requesting the Austro-Hungarians to accept mediation of their dispute with Serbia after limiting their offensive to the capture of Belgrade. The Chancellor has now joined the Kaiser in desperately seeking to avoid the general European war that their prior actions during the crisis made likely. The ability of both, and in particular the Kaiser, to affect the course of events is rapidly slipping away. Once mobilization was on the table, the generals came to the fore. In Germany, this meant Field Marshal Helmuth von Moltke, Chief of Staff of the army. His family had already made its mark on German history - his uncle, Helmuth von Moltke the Elder, had led the Prussian army that crushed first Austria and then France in the German Wars of Unification. Now the nephew faces the culminating crisis of his professional career. From his perspective, even the partial Russian mobilization threatened disaster - every day the German army now waited to mobilize meant that it would fight at a greater and greater disadvantage if/when war came. He makes his case to Bethmann-Hollweg at 1pm, though the Chancellor still holds out hope of a peaceful resolution to the crisis. Later that afternoon, von Moltke learns of the dispositions of the Austro-Hungarian army. To date, they have only mobilized against Serbia, not Russia, and Conrad has also decided to deploy the Austro-Hungarian 2nd Army to the Serbian front, instead of against Russia. This would leave only twenty-five divisions in Galicia on the Russian frontier, far fewer than von Moltke believed necessary - the German war plan relies on Austria-Hungary containing the Russians in the first month of the war while the Germans marched west. That evening he telegrams Conrad directly, begging him to mobilize against Russia, and promising that Germany will mobilize as well. This is a blatant overreach of his authority, and in direct conflict with the efforts of the Kaiser and the Chancellor to preserve the peace. However, the crisis has reached the point where communications between generals are of greater importance than communications between civilians, even if they are monarchs, as is the case with the ongoing 'Willy-Nicky' telegrams. Ultimately, both monarchs, despite the outward appearance of wielding absolute power, are finding themselves incapable of resisting the blandishments of their generals, presented in the language of crisis and national survival.

France: French army is ordered to withdraw ten kilometers from the border with Germany

The French government is steadfast in its support of its Russian ally, but is also eager for Britain to enter the war as well. To this end, the French army is ordered to withdraw ten kilometers from the border with Germany - it is felt essential to show that France is not the aggressor should war break out.

|

|

lordroel

Administrator

Posts: 67,964

Likes: 49,365

|

Post by lordroel on Jul 31, 2019 3:13:16 GMT

Day 4 of the Great War, July 31st 1914Newspaper: Harrisburg Telegraph

1230: Austria orders general mobilization. 1300: Germany declares a state of imminent war, the prelude to general mobilization. 1530: Germany demands that France declare neutrality and surrender the fortresses of Toul and Verdun as guarantees of neutrality. 1730: Britain asks France and Germany to declare their respect for Belgian neutrality. France answers in the affirmative; Germany's answer is evasive. Belgium orders general mobilization. Turkey orders general mobilization. The German light cruiser KÖNIGSBERG sails from Dar-es-Salaam in German East Africa, shadowed by three British cruisers. Midnight: Germany issues an ultimatum to Russia, giving her twelve hours to cancel her mobilization or Germany will mobilize. Map: Daily Telegraph - the Austro-Servian Frontiers

|

|

lordroel

Administrator

Posts: 67,964

Likes: 49,365

|

Post by lordroel on Aug 1, 2019 2:52:25 GMT

Day 5 of the Great War, August 1st 1914

Events hour by hour, Saturday August 1st 1914

As dawn broke on Saturday August 1st 1914, two critical demands made by Germany were awaiting answers. At 7pm the night before, Germany had requested that France state whether it would remain neutral in a Russian-German war. A reply was demanded within 18 hours – by 1pm on Saturday. And at midnight, Germany had given Russia an ultimatum to demobilise within 12 hours.9am: In Paris, Joseph Joffre, commander-in-chief of the army, urged the French cabinet led by René Viviani (pictured right) to announce general mobilisation. France had a plan for deployment – Plan XVII – in the event of war with Germany; it was designed for swift action before Germany could mobilise its reserves. Now Joffre feared the French were losing valuable time – every 24-hour delay, he thought, meant a potential 20km loss of French territory if Germany attacked. 10am In Berlin, Theobald von Bethmann Hollweg, the German chancellor, chaired a Bundesrat (federal council) meeting whose approval was needed for mobilisation or a declaration of war.He had worked hard to maintain peace, he told the leaders of the German states – ‘But we cannot bear Russia’s provocation, if we do not want to abdicate as a Great Power in Europe’. 11am Two hours before Germany’s deadline to France expired, Baron von Schoen, the Kaiser’s ambassador in Paris, presented himself to Viviani to receive France’s reply. He was told that France would act ‘in accordance with her interests’. Shortly afterwards, the Russian ambassador, Alexander Izvolsky, arrived with news of Germany’s ultimatum to Russia. He was desperate to know from Viviani and President Poincaré what France’s intentions were. He feared that the French parliament would not ratify the military alliance with Russia, the terms of which said that France would respond if Germany attacked Russia. When Viviani returned to the cabinet, the order was given to Adolphe Messimy, the war minister, to mobilise, though he was told to hold on to the document until 3.30pm. Meanwhile in London, it was the start of a Bank Holiday weekend, and the prime minister, for one, regretted that the crisis kept him in London and away from Venetia Stanley, the 26-year-old friend with whom he appeared besotted: The Cabinet was to meet at 11am. Beforehand, Sir Edward Grey, the British foreign secretary, telephoned Prince Lichnowsky, the German ambassador (pictured right). Grey asked him whether Germany could give an assurance that France would not be attacked if it remained neutral in a war between Germany and Russia. Lichnowsky understood him to be offering both British neutrality and a guarantee of French neutrality. 11.15am (London time) Lichnowsky sent a telegram to Berlin with what he took to be the offer from Grey and which he believed Grey was taking to Cabinet. The message was not received until shortly after 5pm. 12 noon The German ultimatum to Russia expired without reply. 1pm Asquith’s Cabinet had been in no mood for war, but three days before had ordered preliminary mobilisation of the Royal Navy. Winston Churchill, First Lord of the Admiralty, now argued for full mobilisation. John Morley, president of the Board of Trade, and John Simon, Attorney General, led those opposed, saying Britain should not go to war at all. Herbert Samuel, President of the Local Government Board, emphasised that their decision depended on whether Germany violated Belgian independence or attacked the northern coast of France. During the meeting, Churchill passed notes to Lloyd George, Chancellor of the Exchequer, attempting to win him round. 1.30pm The Cabinet meeting ended and Grey went to meet Paul Cambon, the French ambassador, who had been waiting anxiously at the Foreign Office. Grey could give him no assurances: ‘France must take her own decision at this moment, without reckoning on an assistance we are not now in a position to give.’ Cambon left the meeting shaking and told Sir Arthur Nicolson, Permanent Under-Secretary at the FO: ‘Ils vont nous lâcher – they are going to desert us.’ 3.30pm Grey met Lichnowsky, the German ambassador, who now found the Foreign Secretary simply offering the suggestion that if there was war between Germany and Russia, then Germany and France might agree to stand mobilised but not attack each other. There was no guarantee of neutrality on offer after all. Grey told him that ‘it would be very difficult to restrain English feeling on any violation of Belgian neutrality’ by either France or Germany. 4pm In France, the order for mobilisation was issued, though President Poincaré said it was a precaution and that a peaceful outcome might still be attainable. Posters appeared on the streets of Paris: MOBILISATION GENERALE. LE PREMIER JOUR DE LA MOBILISATION EST LE DIMANCHE 2 AOUT. In Germany, food was being hoarded and savings were withdrawn from the banks. In London the bank rate had doubled overnight and people were queueing at the Bank of England to exchange paper notes for gold. 5pm Germany having had no satisfactory response from Russia, the Kaiser signed the decree of general mobilisation. Speaking to an excited crowd from the balcony of his Berlin palace, he said: ‘In the battle now lying ahead of us, I see no more parties in my Volk. Among us there are only Germans.’ Photo: The German mobilisation order, signed by the Kaiser

5.25pm Grey telegrammed Sir Francis Bertie, British ambassador in Paris, with his suggestion that France and Germany might mobilise but act no further. Baffled, Bertie pointed out that France’s agreement with the Tsar was unlikely to imply inaction if Germany attacked Russia. ‘Am I to enquire precisely what are the obligations of the French under [the] Franco-Russian alliance?’ he asked sarcastically. 5.30pm The telegram sent by Lichnowsky in London at 11.15am arrived in Berlin, shortly after mobilisation had been declared, containing what Lichnowsky thought was an offer of British neutrality. A mildly farcical scene ensued, as Bethmann, the chancellor, and Gottlieb von Jagow, Foreign Minister, rushed to the palace with it. General Helmuth von Moltke, Chief of the General Staff, was recalled as the Kaiser digested the British offer. To Moltke’s despair, the Kaiser announced: ‘Now we can go to war against Russia only. We simply march the whole of our army to the East!’ Since 1905, under the Schlieffen Plan, Germany’s war planning had involved attacking France first. Moltke was distressed at the prospect of this being undone and his mobilisation schedule being wrecked. ‘Once settled it cannot be altered,’ he told the Kaiser. 7pm The German 16th Division was due to move into Luxembourg as part of Moltke’s plan – he knew that Luxembourg’s railways were essential for the route through Belgium to France. Bethmann insisted the invasion could not go ahead while the British offer was pending. But the order did not arrive and an infantry company of the 69th Regiment led by a Lt Feldmann made the first frontier crossing of the war and captured the railway station at Ulflingen. Meanwhile, in St Petersburg, the German ambassador, Count Friedrich Pourtalès, a cousin of Bethmann Hollweg, had handed Germany’s declaration of war to Sergei Sazonov, the Russian foreign minister. Pourtalès had been informing Berlin during late July that Russia was bluffing; now he was in tears, and the two men embraced. 7.30pm Paul Eyschen, Prime Minister of Luxembourg, telegraphed London, Paris and Brussels informing them of the incursion, and protested to Berlin. 8pm A further telegram from Lichnowsky in London arrived in Berlin; this explained that Grey had summoned him to their 3.30pm meeting. Meanwhile, the Kaiser had sent a telegram directly to his cousin George V accepting what he believed was the British offer guaranteeing French neutrality. Mobilisation could not be reversed, he said, but ‘If France offers me neutrality, which must be guaranteed by the British fleet and army, I shall of course refrain from attacking France and employ my troops elsewhere’. Lichnowsky was authorised to promise that Germany would not cross the French frontier before 7pm on Monday August 3, while discussions went on with Britain. 9pm Grey was summoned to Buckingham Palace to draft the King’s reply clearing up the ‘misunderstanding’ that had come out of his conversation with Lichnowsky that afternoon. 10.30pm Crowds were pouring on to the streets of St Petersburg. In Paris, the area around the Gare de l’Est was filling with reservists responding to the mobilisation order. In Berlin, the Kaiser – still hoping for peace with Britain – sent a message to his cousin Tsar Nicholas. He said mobilisation had proceeded because Russia had not responded to Germany’s request and that Russian troops should not be allowed to cross the frontier. 11pm George V’s telegram arrived in Berlin. The Kaiser showed the reply to Moltke, with the words: ‘Now you can do what you want’. In Britain, it was the first day of a bank holiday weekend but holidaymakers were no longer thinking about foreign resorts; the urgent need now was to get home, as the crisis grew. The next morning's Daily Telegraph reported the arrival of the late boat train from Ostend: passengers were telling tales of 'panic' abroad and of their relief at returning to the 'dear old country'. Newspaper: Daily Telegraph - Germany declares war on Russia: the Kaiser addresses the crowd from the balcony of the Imperial Palace, Berlin.

Other events that happened on August 1st 1014 Other events that happened on August 1st 1014

The Turkish battleships SULTAN OSMAN I and RESHADIEH, both about to be delivered, are seized by the Royal Navy. Photo: Sultan Osman I fitting out at Low Walker, after Brazil sold the ship to the Ottoman Empire, but before the British seized her.

Commander of the British Mediterranean Fleet, Admiral Sir Archibald Berkeley Milne, assembled his force at Malta, and on the following day received instructions to shadow the German battlecruiser SMS GOEBEN. With the German ship already sighted, Milne ordered two British battleships to form a blockade at Gibraltar should the German ships try to escape into the Atlantic Ocean.

|

|

lordroel

Administrator

Posts: 67,964

Likes: 49,365

|

Post by lordroel on Aug 2, 2019 8:18:15 GMT

Day 6 of the Great War, August 2nd 1914

Newspaper: New York Tribune

Events hour by hour, Sunday August 2nd 1914 Events hour by hour, Sunday August 2nd 1914

Austria-Hungary was at war with Serbia. Germany had declared war on Russia the day before and had entered Luxembourg as a preliminary to a likely invasion of Belgium and France. Although France and Belgium had mobilised, neither they nor Britain were yet involved in the conflict.

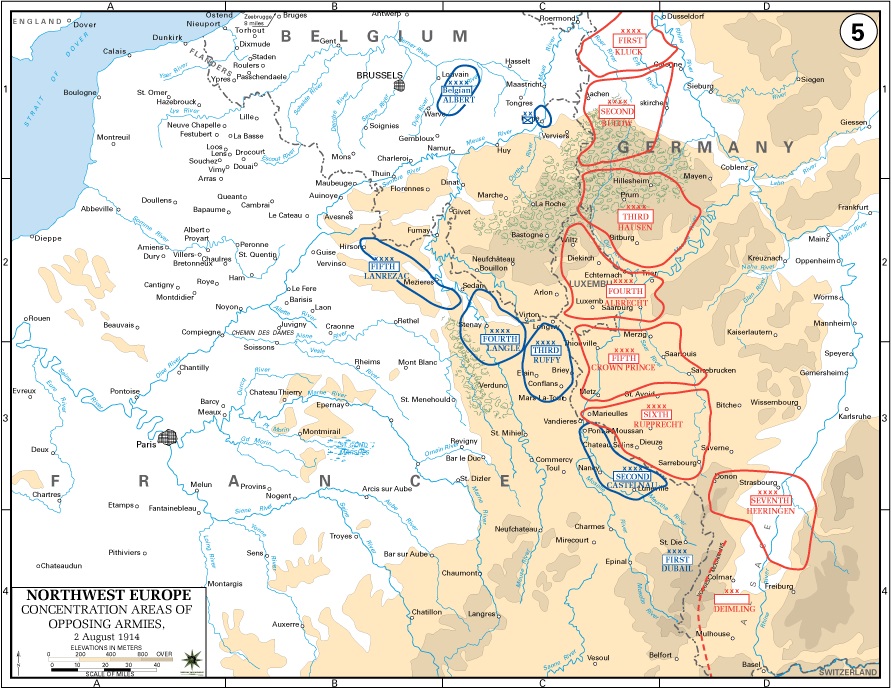

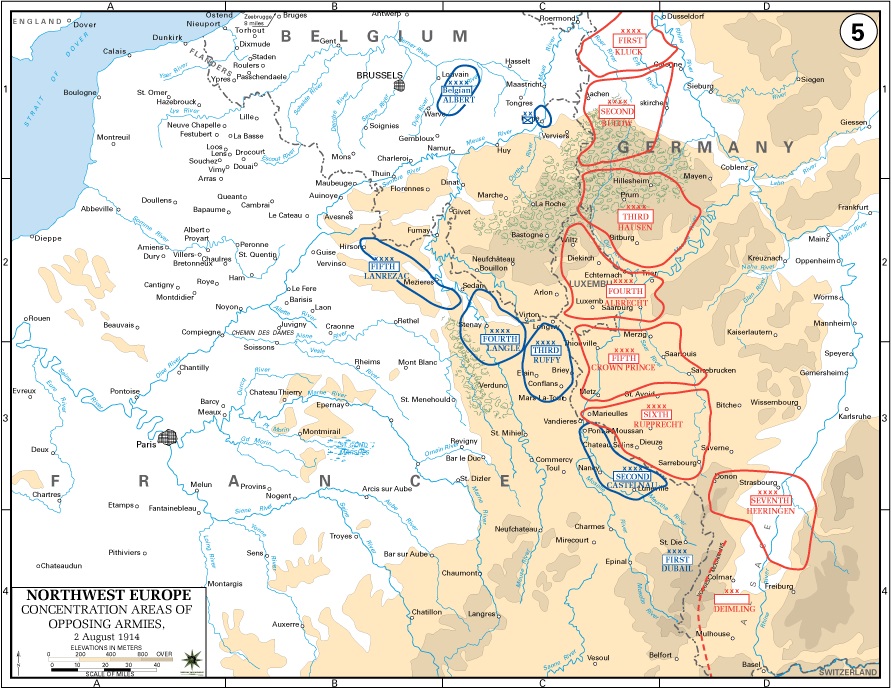

6am: Soon after dawn, reports came via Reuters that Russia had begun an assault on German territory. 7.30am: The German ambassador, Count Pourtalès, and his staff left St Petersburg from the Finland station. In London, Herbert Asquith, the Prime Minister, had his breakfast interrupted by the arrival of Prince Lichnowsky, the German ambassador, who was in an agitated state. Lichnowsky, who had misunderstood Britain’s position the day before, now begged Asquith not to side with France. The Prime Minister (pictured below, right) told him that Germany’s behaviour was rapidly changing British public opinion. By now, Germany had seized the main railway station in Luxembourg. The German chancellor, Bethmann Hollweg, claimed there was no aggressive intent and that this was merely a precaution to secure the railways against a possible French attack. Paul Cambon, the French ambassador in London, asked to meet Sir Edward Grey, the Foreign Secretary. Cambon reminded Grey that the Treaty of London of 1867, signed by the Great Powers, guaranteed Luxembourg's neutrality. The Foreign Secretary responded that the treaty was a ‘collective instrument’ and that if Germany had violated it, Britain did not have to honour it. 11am: Despite it being a Sunday, the Cabinet met. Grey told his colleagues of France's decision to mobilise the previous day. As a consequence of a secret pact made at the 1912 Anglo-French naval talks, France, he said, counted on Britain to secure the English Channel and the North Sea while its own navy patrolled the Mediterranean. The Cabinet was divided, Churchill, the First Lord of the Admiralty, remaining the most clear-sighted about what was coming. 1.30pm: After much discussion the Cabinet agreed, despite polarised opinions, to allow Grey (pictured right) to tell the French that Britain would not allow Germany to use the Channel for operations against northern France. John Burns, President of the Board of Trade, threatened to resign, seeing the decision as an act of hostility to Germany (after the meeting he announced his intention to retire). For his part, Grey said: ‘We have led France to rely upon us and unless we support her in her agony, I cannot continue at the Foreign Office’. The Cabinet agreed to meet again at 6.30pm. 1.45pm: After the meeting Grey took a walk around London Zoo. Asquith and his wife Margot saw the German ambassador Prince Lichnowsky and his wife Mechtilde. The Anglophile prince, who had been awarded an honorary degree at Oxford earlier in the summer, was clearly distressed at the way events were unfolding, as was his wife. 2.20pm: A note was handed to French and German ambassadors in London explaining that the British government would not allow the passage of German ships through the English Channel or the North Sea in order to attack the coasts or shipping of France. Grey gave Cambon, the French ambassador a pledge: ‘If the German fleet comes into the Channel or through the North Sea to undertake hostile operations against the French coasts or shipping, the British Fleet will give all protection in its power’. The British public would have been startled to hear this: there was no commitment made in public and at this point the Cabinet did not know of Germany's impending ultimatum to Belgium. Cambon sent the news to Paris, where his telegram arrived at 8.30pm. 3pm: The Belgian vice consul in Cologne arrived at the Foreign Ministry in Brussels to report that he had been watching troop trains leave Cologne station, heading for the Belgian border, since 6am that day. In Paris, unconfirmed reports were reaching Joseph Joffre, commander-in-chief of the army, that German troops were crossing the French frontier. He argued that a 10km buffer zone, which had been in place, should be lifted and the Cabinet agreed. From St Petersburg, Tsar Nicholas II sent a telegram to London, to his cousin George V: 'I trust your country will not fail to support France and Russia in fighting to maintain the balance of power in Europe. God bless and protect you.’ 3.30pm: The Tsar and his court attended mass in St George’s Hall - the Great Throne Room - in the Winter Palace, St Petersburg. Echoing some words of Alexander I a century before, he swore that he would ‘never make peace as long as one of the enemy is on the soil of the fatherland’. 4pm: There had been Socialist-led demonstrations for peace across Germany in the preceding days, though to little effect. Now a trade union-led demonstration in London brought 10,000 people to Trafalgar Square to protest against war. A rival group sang the National Anthem rather than the Internationale and marched to Buckingham Palace, where the King and Queen waved to them from the balcony. 6.30pm: In London, the Cabinet met for the second time that day. Lloyd George, the Chancellor, was being persuaded of the arguments for resisting Germany, and a small majority was now in favour of action if there was a substantial violation of Belgian neutrality. At the London railway stations serving the south and east coasts, The Daily Telegraph found 'perplexed' holidaymakers discovering that services to the Continent had been whittled down to almost zero. Newspaper: The Daily Telegraph reports the call-up of Navy and Army reserves At Liverpool Street, only one-way tickets to the Hook of Holland were on sale, no returns. Meanwhile, in Brussels, another fateful moment was unfolding. Walter von Below-Saleske, the German minister in the city, handed Viscomte Julien Davignon, the Belgian Foreign Minister, a letter claiming that Germany had evidence France was preparing to cross Belgian territory to attack Germany. In order to defend herself, Germany would need to enter Belgian territory - Germany needed, ‘by the dictate of self-preservation’ to ‘anticipate this hostile attack The first draft of this letter had been written by General Helmuth von Moltke, Chief of the General Staff, on July 26. Belgium was now given 12 hours - until 7am on Monday August 3 - in which to respond. 9pm: King Albert met the Belgian Council of Ministers. They agreed they could not accept the German demands and set about drafting a reply. 12 midnight: The Belgian Council of Ministers' meeting adjourned and the Premier, Foreign Minister and Minister of Justice went to the Foreign Office to draft their reply. 1.30am: The German minister von Below turned up unexpectedly at the Belgian Foreign Office. Germany was uneasy about its ultimatum. Having long assumed that Belgium would not fight, it was now worried that Belgian resistance would hold up its meticulously planned timetable for the invasion of France. In an attempt to goad the Belgians, von Below suggested France had made incursions on German territory and could not therefore be trusted to respect Belgian neutrality. 2.30am: Unmoved by von Below's tactics, Belgian ministers reconvened to approve a reply. Belgium declared itself ‘firmly resolved to repel by all means in its power every attack upon its rights’. The Belgian army had six divisions of infantry and a cavalry division. Germany intended to march 34 divisions through Belgium. Map: Position of the Armies on the Western Front, August 2nd 1914

|

|

lordroel

Administrator

Posts: 67,964

Likes: 49,365

|

Post by lordroel on Aug 3, 2019 6:19:02 GMT

Day 7 of the Great War, August 3rd 1914

Newspaper: The New York Herald

Events hour by hour, Sunday August 3rd 1914 Events hour by hour, Sunday August 3rd 1914

7am: The Belgian Council of State had broken from its deliberations at 4am. Viscomte Julien Davignon, the Foreign Minister, gave his political secretary, Baron de Gaiffier, Belgium's reply to Germany's ultimatum of the evening before, which he handed to Walter von Below-Saleske at the German Legation. Germany's proposed attack on Belgium's independence, it said, 'constitutes a flagrant violation of international law'. 11am: In London, Asquith's Cabinet met. Despite the progress of the day before, there were now four ministers on the verge of resigning over Britain's possible intervention - John Burns, John Simon, Lord Beauchamp and John Morley. Discussion continued for three hours over the statement that Sir Edward Grey (pictured above, right), Foreign Secretary, would make when he addressed the House of Commons that afternoon 2pm: Grey found Prince Lichnowsky, the German ambassador, waiting for him at the Foreign Office, anxious to know if the Cabinet had decided on a declaration of war. Grey told him they had a 'statement of conditions'. In the House, the Speaker took his chair at 2.45pm. Sir Edward Grey ’slipped in almost unnoticed a few moments afterwards’, according to The Daily Telegraph's report the next day. 'Although there were 76 questions on the Order paper only two, and these of minor importance, were answered. As each member whose name stood against a question was called upon, he simply rose and said "Postponed".' The bank rate had soared in previous days and there had been queues of people wanting to exchange paper notes for gold. Lloyd George, Chancellor of the Exchequer, began the business of the day by introducing a Bill to suspend temporarily 'the payment of bills of exchange and payments in pursuance of other obligations’. He then said the City had asked for the bank holiday to be extended by three days. He agreed and said an Order in Council to that effect would be issued that afternoon. Shortly after, Asquith entered the chamber to cheers and explained that the bank holiday applied only to banks and not to other industries. Then it was then Grey’s moment. He began by explaining the background to the crisis, a dispute between Austria and Serbia in which France had become involved because of its alliance with Russia. Britain had a friendship with France - the Entente Cordiale conceived in 1904. Grey had told the French ambassador, he explained to the House, that if there were an attack on France's coast, she would have the support of the Royal Navy. He explained, too, that Britain had asked both France and Germany whether they would respect Belgian neutrality, in accordance with the Treaty of London of 1839; France had said yes, Germany had declined to answer. And now Belgium was threatened with an ultimatum by Germany, and Britain had 'great and vital interests in the independence... of Belgium'. 4.30pm: Grey had spoken for almost an hour, and was nearing his conclusion: We are going to suffer, I am afraid, terribly in this war, whether we are in it or whether we stand aside.... It may be said, I suppose, that we might stand aside, husband our strength, and, whatever happened in the course of this war, at the end of it intervene with effect to put things right and to adjust them to our point of view. If, in a crisis like this, we run away from those obligations of honour and interest as regards the Belgian treaty, I doubt whether, whatever material force, we might have at the end, it would be of very much value in face of the respect that we should have lost – [cheers] – and I do not believe, whether a Great Power stands outside this war or not, it is going to be in a position at the end of this war to exert its material strength [Hear, hear].

4.40pm: Other members rose to speak after Grey. Predictably, some Liberal and Labour MPs spoke against intervention, Conservatives were mostly in favour. But the previously anti-interventionist Liberal Christopher Addison noted that Grey's speech 'satisfied, I think, all the House, with perhaps three or four exceptions, that we were compelled to participate'. Drawing: Sir Edward Grey makes his Statement to the House of Commons

YouTube: a re-enactment of Mr Ramsay MacDonald's response to Sir Edward Grey’s address to Parliament on the eve of War, 3rd August 1914. This speech opposed Britain entering the war. YouTube: a re-enactment of Mr Ramsay MacDonald's response to Sir Edward Grey’s address to Parliament on the eve of War, 3rd August 1914. This speech opposed Britain entering the war.

5pm: Grey returned to the Foreign Office and was cheered by his staff. But in his office, Sir Arthur Nicolson, Permanent Under-Secretary of State, found Grey morose. 'I hate war, I hate war,' he said, banging his fists on his desk. newspaper: The Daily Telegraph

Prince Lichnowsky, German ambassador in London, took Grey's speech to be an indication that Britain still hoped to remain neutral. 6pm: After alleging that the French had crossed into German territory and had also violated Belgian neutrality, Germany sent its ambassador in Paris, Baron Schoen, to deliver a declaration of war to the French premier Rene Viviani Newspaper: A declaration and a mobilisation: how The Daily Telegraph reported the latest developments

7.30pm: The Cabinet met again in London and agreed that Germany must withdraw its ultimatum to Belgium. Afterwards, Grey told Paul Cambon, the French ambassador, that if the Germans did not back down, 'it will be war'. Later that evening, Sir Edward Grey, Foreign Secretary looked out of his window on to St James's Park, where the gas lamps were being lit. Though he could not recall saying the words later, he made his famous remark: The lamps are going out all over Europe; we shall not see them lit again in our lifetime.

The GOEBEN affair, Part 1

On August 3rd the British had three battlecruisers in the Mediterranean sea: INDEFATIGABLE, INDOMITABLE and INFLEXIBLE under the command of Admiral Sir Achibald Berkely Milne, known as 'Arky-Barky'. Under him was Rear-Admiral Thomas Troubridge, commanding four armoured cruisers or heavy cruisers: BLACK PRINCE, DEFENCE, DUKE OF EDINBURGH and WARRIOR. Milne was informed of the breakout of war between Germany and France and of the British ultimatum. He also found that GOEBEN and BRESLAU were coaling at Messina. At this point the Admiralty War Staff decided that Souchon would not attack the French troop convoys, but would make a dash for Gibraltar and try to escape into the Atlantic. Milne was ordered to send INDOMITABLE and INFLEXIBLE to Gibraltar to intercept GOEBEN.

|

|

stevep

Fleet admiral

Posts: 24,832

Likes: 13,222

|

Post by stevep on Aug 3, 2019 11:28:19 GMT

The GOEBEN affair, Part 1

When war was declared the British had three battlecruisers in the Mediterranean sea: INDEFATIGABLE, INDOMITABLE and INFLEXIBLE under the command of Admiral Sir Achibald Berkely Milne, known as 'Arky-Barky'. Under him was Rear-Admiral Thomas Troubridge, commanding four armoured cruisers or heavy cruisers: BLACK PRINCE, DEFENCE, DUKE OF EDINBURGH and WARRIOR. Milne was informed of the breakout of war between Germany and France, and of the British ultimatum. He also found that GOEBEN and BRESLAU were coaling at Messina. At this point the Admiralty War Staff decided that Souchon would not attack the French troop convoys, but would make a dash for Gibraltar and try to escape into the Atlantic. Milne was ordered to send INDOMITABLE and INFLEXIBLE to Gibraltar to intercept GOEBEN. On this last point it might be best to clarify that the dow was by other powers and at this point Britain is still at peace and hence Milne was ordered to track Goeben - the German BC being the main concern - but not to fire on it until there was formally a state of war between Britain and Germany. This was an important factor along with other problems in the debacle that develops. |

|

lordroel

Administrator

Posts: 67,964

Likes: 49,365

|

Post by lordroel on Aug 3, 2019 11:34:34 GMT

The GOEBEN affair, Part 1

When war was declared the British had three battlecruisers in the Mediterranean sea: INDEFATIGABLE, INDOMITABLE and INFLEXIBLE under the command of Admiral Sir Achibald Berkely Milne, known as 'Arky-Barky'. Under him was Rear-Admiral Thomas Troubridge, commanding four armoured cruisers or heavy cruisers: BLACK PRINCE, DEFENCE, DUKE OF EDINBURGH and WARRIOR. Milne was informed of the breakout of war between Germany and France, and of the British ultimatum. He also found that GOEBEN and BRESLAU were coaling at Messina. At this point the Admiralty War Staff decided that Souchon would not attack the French troop convoys, but would make a dash for Gibraltar and try to escape into the Atlantic. Milne was ordered to send INDOMITABLE and INFLEXIBLE to Gibraltar to intercept GOEBEN. On this last point it might be best to clarify that the dow was by other powers and at this point Britain is still at peace and hence Milne was ordered to track Goeben - the German BC being the main concern - but not to fire on it until there was formally a state of war between Britain and Germany. This was an important factor along with other problems in the debacle that develops. A my mistake, i will edit it, thanks for the notice stevep . But the story of GOEBEN and BRESLAU is a interesting one at that. |

|

stevep

Fleet admiral

Posts: 24,832

Likes: 13,222

|

Post by stevep on Aug 3, 2019 13:08:43 GMT

On this last point it might be best to clarify that the dow was by other powers and at this point Britain is still at peace and hence Milne was ordered to track Goeben - the German BC being the main concern - but not to fire on it until there was formally a state of war between Britain and Germany. This was an important factor along with other problems in the debacle that develops. A my mistake, i will edit it, thanks for the notice stevep . But the story of GOEBEN and BRESLAU is a interesting one at that.

Agreed, Depressing in many ways and may have considerably increased the cost and length of the war - although that depends on the intentions of the so called 'Young Turk' regime - but definitely interesting.

|

|

lordroel

Administrator

Posts: 67,964

Likes: 49,365

|

Post by lordroel on Aug 3, 2019 13:10:57 GMT

A my mistake, i will edit it, thanks for the notice stevep . But the story of GOEBEN and BRESLAU is a interesting one at that. Agreed, Depressing in many ways and may have considerably increased the cost and length of the war - although that depends on the intentions of the so called 'Young Turk' regime - but definitely interesting.

As this article mentions: Flight of the SMS Goeben’The Goeben brought more slaughter, more misery and ruin than has ever before been borne within the compass of one ship’’ - Winston Churchill |

|

stevep

Fleet admiral

Posts: 24,832

Likes: 13,222

|

Post by stevep on Aug 3, 2019 17:50:16 GMT

Agreed, Depressing in many ways and may have considerably increased the cost and length of the war - although that depends on the intentions of the so called 'Young Turk' regime - but definitely interesting.

As this article mentions: Flight of the SMS Goeben’The Goeben brought more slaughter, more misery and ruin than has ever before been borne within the compass of one ship’’ - Winston Churchill

That might be Winston somewhat exaggerating the ship's importance as there are a fair number of signs the Turkish regime had already decided to ally with Germany but Goeben didn't help, especially when its attack on Russia while under the Turkish flag opened the war with the Ottomans. However if they had stayed neutral then WWI would almost certainly have been much shorter and less bloody.

Just heard the Ramsey MacDonald speech above and not impressed at all. Grey had actually said that British interests were in danger and that it had a moral responsibility to protect Belgium so he's being disingenuous about his actual stance. Also how the hell could the British government limit its involvement in any conflict Belgium territory unless the other combatants, most especially Germany also agreed to do so? In the OTL developments would he argue for the BEF to surrender rather than retreat into France during the early German victories?

Similarly with the rant about Russia. At the time its a fairly brutal autocratic empire, an understandable focus for hostility by socialists - albeit nothing like as terrible as the very brutal left wing autocratic empire it became after the war. How could the British government, reluctantly entering into a massive war, make statements about what would happen to a large and distant empire that happened to be allied in the forthcoming conflict? Is he expecting Britain to demand social or political change in Russia and refuse to support it even if that meant losing the war against Germany? Sounds like he's using it to give an excuse for his refusal to support a dow.

|

|

lordroel

Administrator

Posts: 67,964

Likes: 49,365

|

Post by lordroel on Aug 3, 2019 17:59:42 GMT

As this article mentions: Flight of the SMS Goeben’The Goeben brought more slaughter, more misery and ruin than has ever before been borne within the compass of one ship’’ - Winston Churchill That might be Winston somewhat exaggerating the ship's importance as there are a fair number of signs the Turkish regime had already decided to ally with Germany but Goeben didn't help, especially when its attack on Russia while under the Turkish flag opened the war with the Ottomans. However if they had stayed neutral then WWI would almost certainly have been much shorter and less bloody.

Well if the British did not size control of the Turkish battleships SULTAN OSMAN I and RESHADIEH who where under construction, then i wonder if the Turks would have taken over GOEBEN and BRESLAU so easy. |

|

stevep

Fleet admiral

Posts: 24,832

Likes: 13,222

|

Post by stevep on Aug 3, 2019 18:18:02 GMT

That might be Winston somewhat exaggerating the ship's importance as there are a fair number of signs the Turkish regime had already decided to ally with Germany but Goeben didn't help, especially when its attack on Russia while under the Turkish flag opened the war with the Ottomans. However if they had stayed neutral then WWI would almost certainly have been much shorter and less bloody.

Well if the British did not size control of the Turkish battleships SULTAN OSMAN I and RESHADIEH who where under construction, then i wonder if the Turks would have taken over GOEBEN and BRESLAU so easy.

I suspect if the German ships had escaped to Istanbul as OTL they would. As the attack on the Crimean showed they were still effectively under German control and better to have the in the hands of Turkey a friendly power already negotiating with Germany for their entry into the war, at least by a number of sources than seized for breaching neutrality rules or forced to sail out of Turkish waters to probably quickly be overwhelmed by a markedly larger RN force.

|

|